Everyone has an opinion on education – and about what politicians should do about education systems. But, when does public opinion matter? In a new book, “A Loud but Noisy Signal?” Marius Busemeyer, Erik Neimanns, and I explain that public opinion matters when the issue is salient and the public agrees on which direction to take policy responses.

Everyone loves education!

Education is an extremely popular topic. Surveys have shown repeatedly that large majorities demand higher investments in education and regard education as an important policy area.

However, do these large majorities continue to support educational investments when the costs become visible? That is, when respondents are informed that higher investments would come at the expense of higher taxes, higher public debt, or cutbacks in other welfare areas? And what exactly would they like to spend money on? On schools, childcare, or post-secondary education? What do people think about private schools, parental school choice, and school autonomy?

We simply didn’t know the answers to these questions because existing comparative public opinion surveys hadn’t surveyed attitudes on these detailed – but crucial – aspects of education policy.

Accordingly, we conducted a large representative public opinion survey in eight European countries on citizens’ attitudes towards education and social policy (more information here).

…or don’t they?

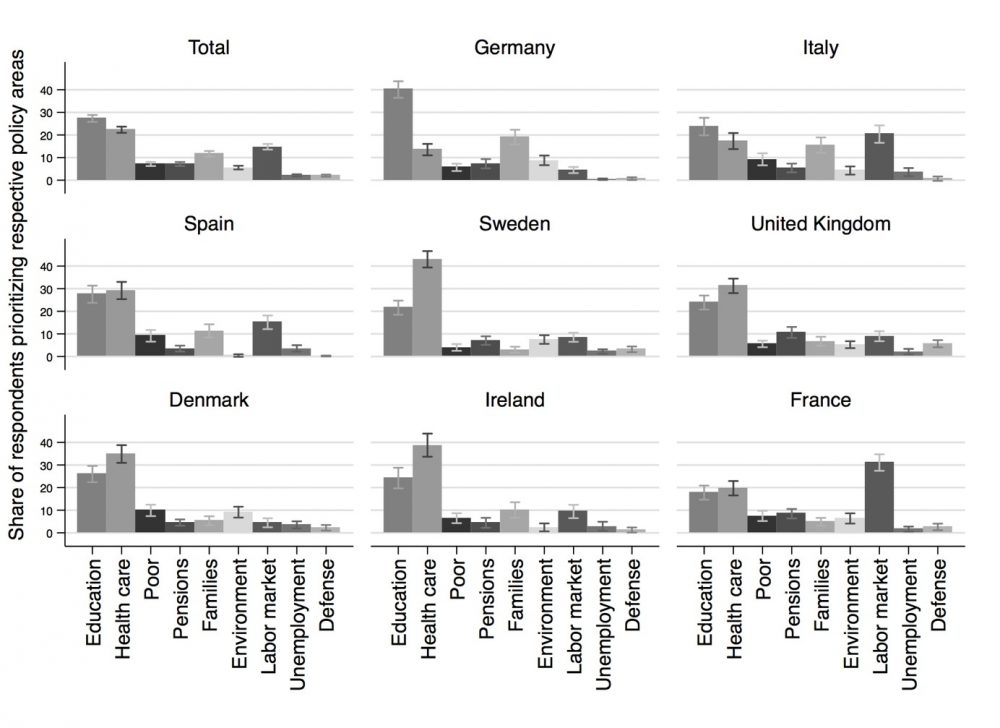

Education remains very popular even when in direct competition with other policy areas. We asked, for example, for which policy area respondents would spend more money if they could choose only one. Figure 1 shows the results. We see that education features prominently in all countries – only health care is even more popular in some countries (and labour markets in France).

Figure 1: Which policy area do respondents prioritise when forced to choose only one?

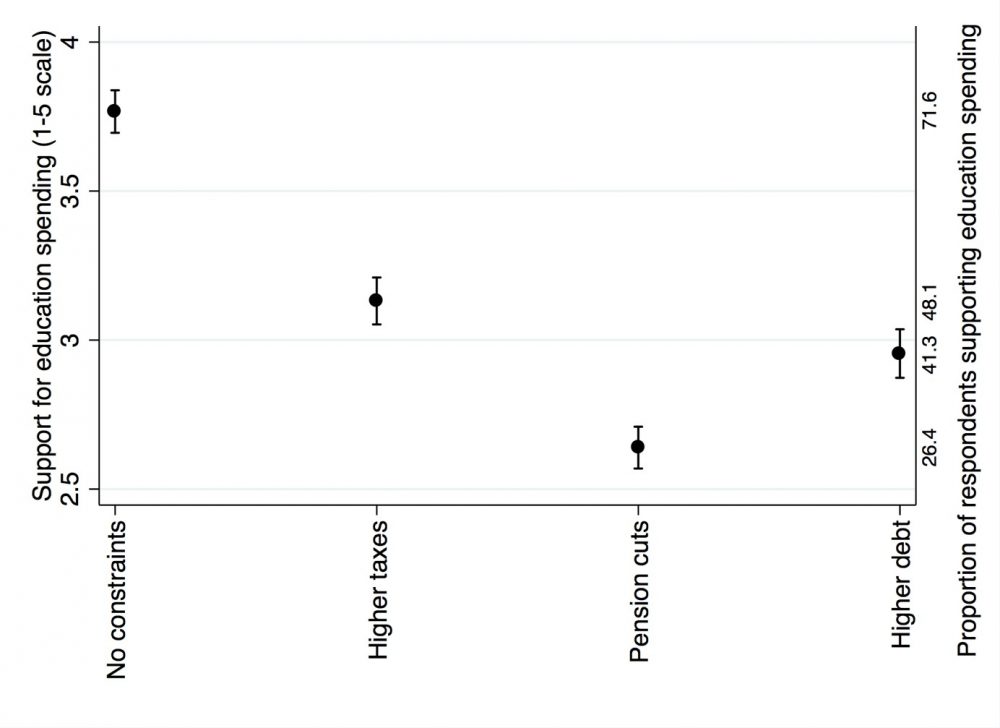

Education also remains popular when the costs are made visible – but the support levels decrease substantially. To illustrate, Figure 2 shows findings from a survey experiment: 72 percent support education spending in general. Yet, when reminded that higher spending would be funded by higher taxes, support levels decrease to 48 percent. Even more unpopular is funding via higher public debt (41%).

– But what respondents oppose the most is if additional education spending would be financed by cutbacks in other welfare areas, like pensions (yet, still 25 percent support this).

In today’s so-called Silver Age of the welfare state such policy trade-offs are omnipresent. Policy-makers and citizens are repeatedly forced to make tough choices in trade-off environments.

Figure 2: Support for higher educational investment in various trade-off scenarios (split sample).

Does it matter what people want?

For public opinion to matter it is important how salient a topic is, i.e. its importance in public discussions. Some topics are very salient, such as changes in the number of years children stay at school or the introduction of tuition fees. On these issues, most people have an opinion and find the topic relevant.

Other topics are much less salient, for example whether vocational schools should offer more math courses or how higher education institutions should be internally steered. Some people might really care about these issues – but the majority doesn’t.

High salience is a necessary condition for public opinion influence: public opinion only plays a role for policy-making when an issue is salient.

Yet, salience alone is not enough

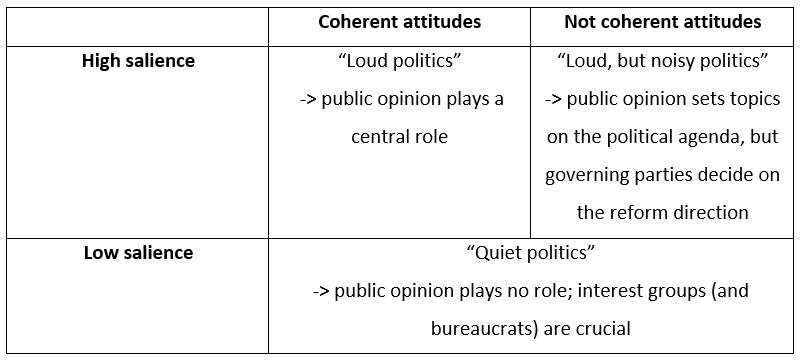

Yet, it doesn’t stop here. Salience alone cannot explain what role public opinion plays in policy reforms. In order to understand this better, we additionally need to look at the degree to which citizens agree or disagree on certain issues. We call this “coherence”.

Some topics are salient and most people share the same opinion. In these instances, public opinion sends a “loud and clear signal” to policy-makers, who have to respond (for electoral reasons). Public opinion accordingly plays an important role. We call this “Loud Politics”.

Other topics are equally salient, but public opinion is split on the direction of reform: “Loud but Noisy Politics”. Public opinion sends a very ambiguous signal to policy-makers aka “we all want something, but we disagree on what we want!”. In this scenario public opinion can help to bring an issue on the political agenda – but what direction policy takes is ultimately decided by the respective governing parties.

Table 1: When public opinion matters for policy-making

So, under what conditions is public opinion relevant?

Our book shows that the answer depends on two elements: salience and coherence. Accordingly, we now understand better now why it sometimes matters what people want, and sometimes doesn’t. This also is relevant for citizens, parties, and other political stakeholders, as it helps understand under what conditions people can get their voice heard.

The theoretical model equally travels to all other (social) policy areas, helping to explain why public opinion sometimes, but not always, matters.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.