March 2022 marks a big step forward for children in Italy. For the first time in its history, Italy introduces a universal child allowance: a ‘historical act’ in the words of the Minister for Family and Equal Opportunities, Elena Bonetti. The new allowance overcomes inconsistencies of the previous system by not discriminating based on employment status. Moreover, it will guarantee a minimum child benefit to any Italian household that applies for it; no condition attached.

The new Assegno Unico Universale (AUU) is a universal allowance granted to each child up to the age of 21 which simplifies the previous support system for parenthood by guaranteeing a minimum amount to all families with dependent children.

The new benefit has four key features:

- It will be paid for each dependent minor child, regardless of family income, but with higher amounts for lower income families;

- It will cover children even before they are born: the benefit can be claimed from the seventh month of pregnancy;

- It will be paid right up to the age of 21 for dependent children who are in education or training, and for those who are unemployed or employed but earning less than 8.000 euros per year;

- It will be paid for each dependent child with disability through to adulthood.

Families must apply to access the benefit by reporting their Equivalent Economic Situation Indicator (ISEE), which measures household income and assets. The benefit amount then decreases progressively: it goes from a maximum of 175 euros for each child for families with an ISEE of 15 thousand euros or less, to a minimum of 50 euros for each minor child with no ISEE or with ISEE equal or higher than 40 thousand euros (see Table 1).

As the table from the Ministry of Economy and Finance shows below, the AUU also grants further bonuses to larger families, mothers under the age of 21, and children with mild or severe disability. For instance, households with 4 or more children receive an additional bonus of 100 euros per month.

The AUU simplifies a previously complicated and discriminating system which was based on two main measures: Allowance for Family Unit (AFN) and tax deductions. AFN was only granted to employees already included in their salaries, excluding self-employed and unemployed individuals. Minor additional benefits were available to very specific constituencies or for short terms, such as the Birth Allowance and the Birth Premium.

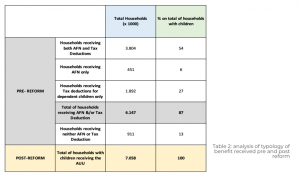

Now families will receive a single allowance through a monthly wire transfer from the state. This rationalisation will allow more families to receive the benefit: the share of families covered rises from 87% under the old system to 100% (see Table 2).

Because the new allowance does not discriminate based on employment status it overcomes a series of inconsistencies and violations of horizontal and vertical equity of the previous system.

The old mechanism discriminated against solo-parent families because a higher number of earners in the household increased the value of the allowance. It was also inefficient in reaching the poorest families. Indeed, families with an annual income of lower than 10,000 € could not benefit from tax deductions for dependent children because of their inability to reach the minimum income threshold. Further, even though the ANF was means-tested, it could only be accessed by those who were employed in the formal sector. The informal market is still considerable in Italy. Thus, low-income families reliant on casual or intermittent jobs were excluded from this benefit or did receive such a low amount that was insufficient for supporting them.

Data from the Ministry of Economics and Finances, shows that almost half a million households received only the ANF as they did not have sufficient income to also benefit from the tax deductions. 40% of households with children did not have access to the ANF, mainly because their family income did not include sufficient earnings from formal employment.

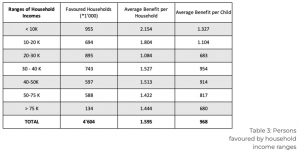

The reform will not only extend the number of beneficiaries but will also strengthen the benefits for all categories, including those already benefiting from the previous instruments. The Ministry estimates that thanks to the AUU, out of a total of more than 7 million households with dependent children under the age of 21, 4.6 million (65 percent of the total) will experience an increase in their disposable income by 1,600 euros per year on average. The advantage is due to an additional 6 billion to the 13 billion spent under the previous system, an increase of about half of the resources previously allocated to parenting and family support. To a lesser extent, the more rational design of the instrument also contributes to this, allowing resources to be better concentrated. Most of the households covered by AUU (almost 90%) will instead see little change in their income. Despite the increases being distributed over all classes of income, the maximum average benefit will indeed be registered in households under 10,000 Euros of income (Table 3).