The major contribution of the Indian subcontinent to the British effort in the First World War is now receiving renewed recognition, not least by Lord Parekh in his June address to Asia House. As a historian of the Caribbean, Richard Smith has been uncovering how news of Indian mobilisation encouraged support for the war effort in the British West Indian territories.

The major contribution of the Indian subcontinent to the British effort in the First World War is now receiving renewed recognition, not least by Lord Parekh in his June address to Asia House. As a historian of the Caribbean, Richard Smith has been uncovering how news of Indian mobilisation encouraged support for the war effort in the British West Indian territories.

This post forms part of a series on India and World War I. Click here to view more posts.

On 28 August 1914, the Marquess of Crewe, Secretary of State for India, addressed the House of Lords to support the deployment of Indian troops in Europe in support of the beleaguered British Expeditionary Force. Crewe asserted that the reputation of the Indian Army would be undermined if this suggestion was not acted upon, especially as France had begun to send battalions of the Tirailleurs Sénégalais from their African garrisons to the Western Front. The Marquess’s statement was widely circulated in the British West Indian press which commented favourably on the military prowess of the Indian Expeditionary Force (IEF). The Jamaican Daily Chronicle reported that “Great Britain will throw her splendid Indian troops against the German forces”. By mid-September, even before the first IEF troops had actually disembarked at Marseille, the Jamaica Times printed rumours that the Indians had defeated elite German regiments. The same paper later commented that the Indians were superior to the Germans and the equal of other Europeans, suggesting it was “almost a slur on our Indian troops to praise their success in the fighting in France as if it were a thing to be surprised at”.

Marcus Garvey, leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, issued a declaration of loyalty for the British Empire in mid-September. Following this example, other West Indians were keen to express support, particularly for non-whites soldiers serving the imperial cause. Colonial Office correspondence from this time includes a letter to Lord Kitchener from “A Loyal Subject of the West Indies Island (jamaica) [sic]” who enclosed a donation “for my brothers black and indian [sic] troop who are at the front fighting to defend our majesty’s Empire.”

The deployment of the Indian Army coincided with calls for the West India Regiment to be sent to France and for further contingents of West Indian volunteers to be recruited. However, such proposals were rejected by the Colonial Office on the grounds that the West Indian colonies would better serve the war effort producing raw materials and food. Imperial martial race discourses represented Indian troops as more efficient than black West Indian soldiers. Originally established to protect British Caribbean possessions from the late eighteenth century, the West India Regiment had later proven indispensable to British imperial campaigns in West Africa, from the 1870s. However, its soldiers were characterised as rash and impetuous by many observers. In the wake of the 1857 Mutiny, the Indian Army had redefined the recruiting grounds from which the Indian Army was drawn to match martial race theories around reliability and military prowess. The process of Indianisation and the emergence of the Indian Army as a distinct organisation with its own culture and esprit de corps also underpinned the preference for Indian over West Indian, and later African, soldiers.

However, representations of black and Indian masculinity within the British West Indian territories, disrupted the martial race discourses of empire. Since the importation of indentured Indian labour to the British West Indies after slave emancipation in the 1840s, debate raged about whether black or Indian men were more suitable for plantation labour. Black West Indian masculinity came to be defined, not only in opposition to ideals of white masculinity, but also in relation to images of the Indian men who provided an alternative source of labour on the plantations. The Sanderson Commission of 1910, established to investigate conditions under the indentured labour system, found that the continued association of black men with physical prowess meant that Indian labour was often relegated to the ‘water work’ and ‘dirty work’ which black men refused as ‘women’s work’. Indians, however, were seen as more suitable for tasks requiring intelligence or dexterity – “any delicate work … such as pruning cocoa, and pruning bananas … that [could not] be safely left to the ordinary negro labourer”. Against this background black male West Indians may have a felt strong pressure to prove their masculinity through military service, particularly in the colonies of Trinidad and British Guyana where Indian indentured labour was most widespread.

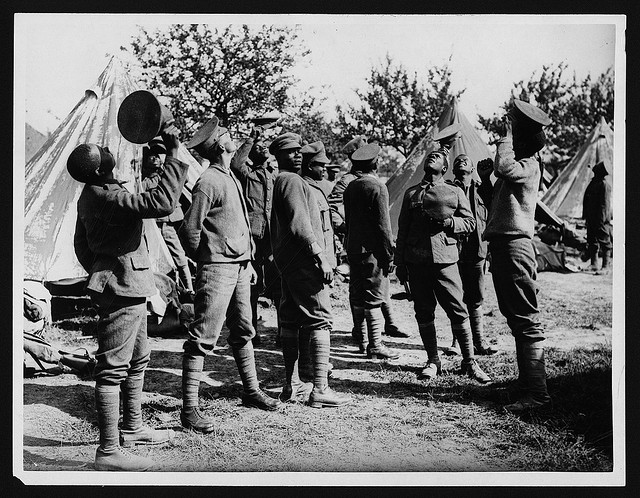

In October 1915, the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR) was formed to accommodate a rising number of volunteers coming forward from the region. Ironically, volunteers for the BWIR of Indian heritage were often turned down due to enlistment clauses which stipulated proficiency in English and acceptance of the standard British Army food ration, rather than the more culturally appropriate diet issued to the Indian Army. The racial military hierarchy of the British Empire, evident at the beginning of the war, remained largely intact. While the Indian Army served on all the major fronts, the twelve battalions of the BWIR were largely confined to the role of labour battalions in France, Belgium and Italy. Only two battalions were deployed as combat troops against the Turkish Army in the Middle East from 1917 and a small detachment saw front-line service in East Africa.

About the Author

Dr Richard Smith teaches in the Department of Media and Communications, Goldsmiths University of London. He has written widely on the West Indian experience during the First World War.

Dr Richard Smith teaches in the Department of Media and Communications, Goldsmiths University of London. He has written widely on the West Indian experience during the First World War.

Read about the British West Indies Regiment in action in Palestine here:

http://www.kaiserscross.com/304501/319801.html

some tentative propositions….

Indians may have also been excluded from the BWIR because they were seen as quintessentially coolies, and therefore not fit for recruitment as combatants,…They were more valuable on the plantation given the boom in cane sugar prices once supplies of European beet sugar were cut off. This was particularly the case because the suspension of indentured migration from India in March 1917 meant that fresh supplies of this labour force could no longer be counted uponSecondly since British West Indian soldiers staked their claim to an equality of pay with British soldiers on similar cultural standards, – Christianity, the English language and similar food habits – they necessarily distanced themselves from the Indian settler. radhika singha