Indian soldiers played a key role in British campaigns in Europe during World War I but the Middle East was the most important theatre of war for India. Vedica Kant offers an insight into the traumatic experiences of over half a million Indians who participated in the ill-fated Mesopotamia campaign.

Indian soldiers played a key role in British campaigns in Europe during World War I but the Middle East was the most important theatre of war for India. Vedica Kant offers an insight into the traumatic experiences of over half a million Indians who participated in the ill-fated Mesopotamia campaign.

In Istanbul’s Asian neighbourhood of Kadıköy, hidden near the fairy-castle-like Haydarpaşa railway station, lies the secluded and charming Haydarpaşa English Cemetery. An oasis of quiet in the middle of the hustle of one of Istanbul’s main commuter hubs, the perfectly manicured cemetery (maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) is reminiscent of an English garden in bloom.

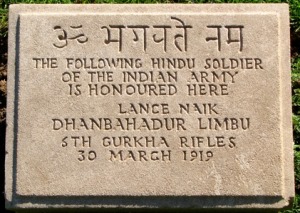

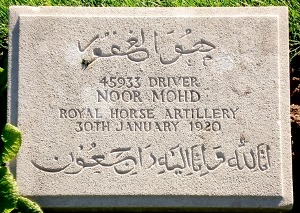

The cemetery was initially established as a burial ground for the British casualties of the Crimean War (1854–1856). Nearby is the Selimiye Barracks where Florence Nightingale gained fame for caring for the injured and wounded during that conflict. But the cemetery does not commemorate only the Crimean War dead. It also honours the memory of nearly 150 Hindu, Muslim and Sikh soldiers of the Indian Army who had died as Prisoners of War as a result of their participation in the Mesopotamia campaign of the First World War.

Haydarpaşa English Cemetery. Image credit: Vedica Kant

Given the general lack of knowledge about India’s historical connections with the Middle East and India’s expansive role in the First World War, the fact that Indian soldiers fought in the Middle East during this war might be a revelation for an Indian traveller who might have stumbled upon the site. In fact, the Middle East was the most important theatre of war for India during the Great War. Four of the six expeditionary forces India provided for the war effort were sent into action in the Middle East. Indian infantry and cavalry played an important role in protecting the Suez Canal in Egypt and later in the battle for Palestine, where Indian cavalry played a crucial role in gaining control of the city of Haifa. Indian mountain batteries and infantry units also played an important role in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign.

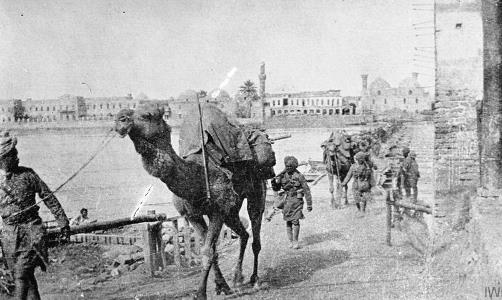

However, the most significant campaign of the war for Indian troops took place in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). The Mesopotamia campaign started off as an entirely Indian Army operation. 588,717 Indians – i.e. nearly 40 per cent of all Indians who were involved in World War I – served in Mesopotamia, more than in any other single campaign during the war. In a parallel with Iraq’s more contemporary history, the decision to expand the conflict to Mesopotamia was driven by the desire for oil. The Government of India decided to deploy an expeditionary force in the region to protect its oil interests there. For a majority of Indians their experience of the war was not that of a bitter European winter but of the dramatic swings between extreme heat and dust and the chilly winters of the Arabian Desert.

In Mesopotamia, disease festered and food and water were scarce. Despite the challenges, for the first year or so of the Mesopotamia campaign (from April 1914 to late 1915) the British-Indian troops met with such little resistance from the Ottoman army that the campaign started to be described as a ‘river picnic’. Then, in November 1915 at Ctesiphon, just south of Baghdad, the army ran into a large and well-entrenched Ottoman force. Instead of the expected 6,000 Ottoman troops, the Indian army was confronted with some 25,000 of the enemy. The advance was blocked and the army driven back to the small town of Kut al-Amara. With just one month’s food supplies the Indian force endured a siege of five months before the lack of food forced surrender in April 1916. The surrender, considered one of Britain’s most abject military defeats at the time, led to about 10,000 Indian soldiers being taken captive by the Ottomans. For most of the soldiers captured this was just the beginning of a torturous period of captivity. Some were made to walk around 500 miles to Ras el-Ain in present-day Syria. Other travelled even further, beyond the Taurus Mountains, until they reached POW camps in Anatolia. It is these soldiers who are commemorated at the cemetery in Istanbul.

As the scholar Santanu Das has rightly pointed out, there were different wars and war experiences for Indians just as there were for Europeans. The Indian campaign in Mesopotamia is particularly interesting because it raises all sorts of questions about the complex and confusing encounters with a new place, between cultures and, indeed, over the question of religion. The front against the Ottoman army was fraught with many more complications (especially once the Ottomans declared a jihad against the Allied Forces) than sending Indian troops to fight the Germans in France and Flanders. For years the Ottoman Empire had been an ally of the British, and the Ottoman sultan was recognised as the caliph by Indian Muslims; there was genuine worry amongst the British administration that Muslim Indian soldiers might refuse to fight against the Ottomans. In the end these fears were unfounded. Most Indian Muslim soldiers remained steadfastly loyal to the British even against the pull of religion. Yet it does raise questions as to the emotions some of these soldiers felt and the rationalisations they might have had to make.

The memorials to the fallen soldiers that remain help in reminding us of the strange experience these soldiers had, fighting a strange war in a strange land against people they had never met before and with whom they had no real enmity. In a journal he kept throughout the war and his period in captivity, Sisir Sarbadhikari (a stretcher bearer from the Bengal Ambulance Corps) notes about his interactions with Turks:

“One thing they always said was this: What are you going to gain from this war? Why are we cutting each other’s throats? You live in Hindustan, we live in Turkey, neither of us have ever met, we have no quarrel with each other, and yet at the behest of a couple of men we’ve become enemies overnight.”

About the Author

Vedica Kant is the author of the recently published book ‘If I die here, who will remember me?’: India and the First World War. Vedica has an M.Phil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Oxford and has written widely about WWI from Indian and Ottoman perspectives.

Vedica Kant is the author of the recently published book ‘If I die here, who will remember me?’: India and the First World War. Vedica has an M.Phil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Oxford and has written widely about WWI from Indian and Ottoman perspectives.

what an insight! Thanks

can one get the book in the UK?

Hi Roni, the book should be available at the end of the month on Amazon (http://www.amazon.co.uk/India-First-World-War-Remember/dp/8174369791/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1415715218&sr=1-1) and also at Waterstones (http://www.waterstones.com/waterstonesweb/products/vedica+kant/india+and+the+first+world+war/10830291/)

If I’m not mistaken, then India sent seven, not six, expeditionary forces (A to G), but you’ve mentioned that there were only six.

The Haidar Pasha Memorial largely commemorates Indians who died post the Armistice and most casualties are from the Army of the Black Sea and not the POWs from Mesopotamia. Nearly all the casualties are from 1919-20. Only one British officer of the 103rd Mahratta Light Infantry and 2 Indian soldiers (one from the 48th Pioneers and the other from the 7th Duke of Cannaught’s Own Rajputs) who were POWs are buried in the Haidar Pasha Cemetery