The smart city concept holds an array of opportunities for future of cities and city-making in India. However, It is critical that urban planners in India acknowledge technology as merely a tool and engage with it in a way that affirms values and addresses the most pressing goals, writes Shabana Shiraz.

The smart city concept holds an array of opportunities for future of cities and city-making in India. However, It is critical that urban planners in India acknowledge technology as merely a tool and engage with it in a way that affirms values and addresses the most pressing goals, writes Shabana Shiraz.

“Technology amplifies human intent and capacity; it does not substitute for them”, concluded Kentaro Toyoma, assistant director and co-founder of Microsoft Research India, in his TEDx talk. This conclusion came after five years of exploring ways to apply electronic technologies for development in India.

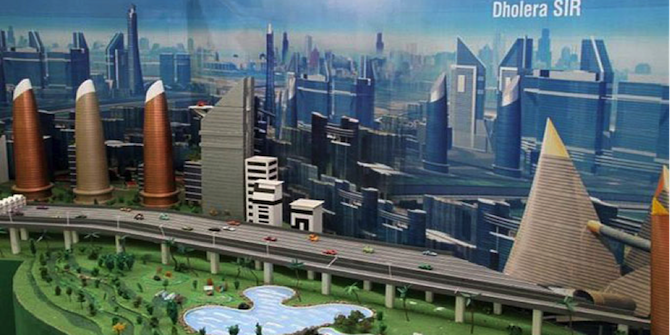

Indian Prime Minister Shri. Narendra Modi’s ambitious ‘100 smart cities’ project has been a subject of praise as well as constant critique within the urban policy and practice circles in India. It is applauded for its aim of achieving 9% GDP growth, and critiqued for the lack of clarity in the vision and its disregard for perennial urban challenges of Indian cities like, poverty and exclusion.

The concept note released by the Ministry of Urban Development, seeks to decipher the concept as well as the implementation and operational mechanisms of the coveted smart cities scheme. This promises to unleash another round of mixed emotions. While the note still lacks a basic or even a working definition of smart cities for the Indian context, it does borrow a developed world ideology dominated by digital infrastructure; state-of-the-art sensor networks, real time governance and other smart technologies while also recognising the contextual nuances of decentralisation. This idea supports a vision to create highly networked, environmentally sustainable, energy efficient and seamlessly managed Indian cities; cities capable of attracting investments and supporting a high standard of living while also being self-sustaining.

The idea of smart cities thus creates an urban utopia where technology comes to the rescue of every challenge. What could not be solved through decentralisation and a series of urban sector reforms, can now be solved by inculcating ‘smartness’ into our cities.

Most of the existing imagery of smart cities is being propagated by industry-led consortiums. The imagery focuses on highly technical and specialised solutions like smart-grid; GPS based land record-monitoring, intelligent transportation systems, and so on. The dialogue focuses on use of available solutions, rather than assessment or articulation of needs by urban planners and managers.

Although not deliberate, these imaginaries and dialogues may result into alienation of two crucial stakeholders from the process of city making: the citizen and the urban planner. The concept note highlights the urban challenges prevalent in Indian cities and the use of technology tools to address the same, however little is elaborated in terms of empowering the citizenry through use of these tools. The lack of a benchmark on citizen participation further makes the inadequacy of the vision to address the creation of empowered citizenry, apparent. Further, by advocating and emphasising the technology solutions available, the plan of action is laid out and the role of an urban planner is almost made redundant. There seems to be no need for identifying contextual challenges and specific needs along with understanding the best-fit technology that can be integrated seamlessly into the existing urban fabric of the cities. Thus, the focus on solutions de-emphasises a rather complex process of urban planning and ignores the potential of utilising smart city technologies for capturing and using data for evidence-based planning.

A smart city vision for India thus needs to acknowledge the roles, and address the needs, of both the above-mentioned stakeholders in order to gain wider acceptability as well as have a better chance of becoming a reality.

A well-articulated smart city vision has a potential to transform city making and urban citizenship paradigms to ones that involve greater use of technology for gathering, visualising, analysing and patterning data for informed urban planning and making relevant data available in a consumable format to the citizens for greater transparency and informed decision-making.

”The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanisation.”– David Harvey.

These are both empowering as well as challenging times for an urban planner in Indian. They are empowered thanks to the availability of data that can aid in evidence-based urban planning. At the same time, the urban planner stands at the crucial point of choice, where he/she needs to make a choice between technology-based urban planning and citizen-centric urban planning. With the available technology solutions, does one plan cities on the New Songdo template that is being increasingly propagated? Or should one strive to nurture and fully develop the nascent ideas of citizen participation that were introduced through recent urban reforms in India? Of course, one aspires to achieve a middle ground rather than venturing too far on either sides of the spectrum. However, this may require the planner to adapt to technology advancements whilst advocating community values. Described by a noted American planning theorist Paul Davidoff, advocacy based planning is one that not only takes into account facts and technical information, but also considers ‘values’, (social, economic, political, historical etc.)

It is critical that urban planners in India acknowledge the role of technology as merely a tool and engage with it in a way that affirms the most contextual values and utilise it to achieve the most pressing goals. The smart cities framework should not aim to simply strengthen the consultative participation through use of technology for monitoring urban services, but also to empower citizens by providing them consumable data derived out of smart city tools, enabling them to play a substantial role in the city making itself. The Swedes have been practicing this since some time now.

The smart city concept holds an array of opportunities for future of cities and city making in India. However, it is the articulation of a well-rounded and contextual vision that shall set us on the path of realising and making most of these opportunities.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Shabana Shiraz is an urban practitioner with a keen interest in participatory pro poor urban planning and governance. Her perennial fascination for cities and its people has prompted her to be actively engaged in research and dialogue revolving around exploring how both these can work towards the benefit of each other. She is currently studying for an MSc in Development Management at LSE.

Shabana Shiraz is an urban practitioner with a keen interest in participatory pro poor urban planning and governance. Her perennial fascination for cities and its people has prompted her to be actively engaged in research and dialogue revolving around exploring how both these can work towards the benefit of each other. She is currently studying for an MSc in Development Management at LSE.