Rajesh Venugopal reflects on Sri Lanka’s surprise election result and considers what it might mean for the island nation. He highlights that the new president is weak and now faces the task of dealing with both problems that persist from the civil war and issues such as corruption, inflation and the abuse of power which plagued the governments of his predecessor.

Rajesh Venugopal reflects on Sri Lanka’s surprise election result and considers what it might mean for the island nation. He highlights that the new president is weak and now faces the task of dealing with both problems that persist from the civil war and issues such as corruption, inflation and the abuse of power which plagued the governments of his predecessor.

A few weeks ago, it was a foregone conclusion that Sri Lanka’s former president Mahinda Rajapaksa would win the elections and extend his decade in power by another five years. His son Namal tweeted ‘this will be an easy win’. But the country’s long demoralised, perennially defeated, and deeply compromised opposition pulled a surprise candidate out of the hat and went on to win a clear majority.

Sri Lanka’s new president Maithripala Sirisena, was not only a long-time friend and party loyalist of Rajapakse, but was at the time of his defection, Health Minister, and also general secretary of the ruling Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). On the day of judgment, Sirisena won 51% to Rajapakse’s 47% and was within hours, sworn in as the new president. What do these election results reveal, and what does the future hold for Sri Lanka?

First, the elections revealed the extent to which Sri Lanka’s ethnic and religious cleavages dictate electoral outcomes. Sirisena won a majority in virtually every polling district with a large minority presence, either Tamil, Muslim, or Catholic (for maps and results, click here.)

Negombo’s Catholic voters gave Sirisena 67% of the votes. Jaffna Tamils upped that to 78%. The Muslims of Muttur gave him a thumping 87.5% majority. With the exception of Sirisena’s own home district of Polonnaruwa, his only victories were in minority-dominated areas while Rajapakse retained a majority in every district with a Sinhala-Buddhist majority.

Second, despite that the outcome of this election hinged not on the minority vote but on the majority. Rajapakse lost because his core Sinhala-Buddhist supporters were abandoning him. In the aftermath of the war in 2010, Rajapakse carried 65% of the Sinhala-Buddhist vote. This time it was only 55%, which means he lost 750,000 of his core voters. Why did this happen? The answer is simply, anti-incumbency. Rajapakse has already been in power for 10 years, and the war, on which he based his political success, ended more than five years ago. Of greater concern now to those voters are issues such as corruption, inflation, and the abuse of power, none of which can be blamed on the LTTE.

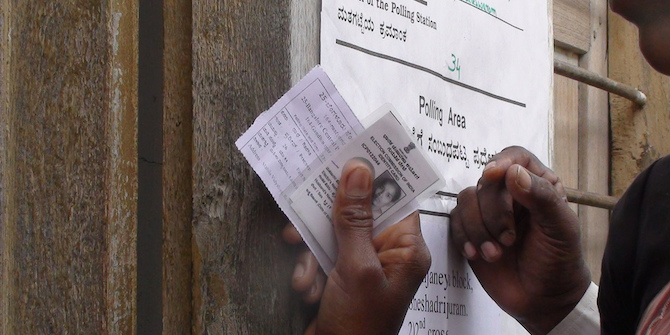

Third, this was an unusually ‘clean’ election with an 81% turnout. Although there were scattered reports of irregularities, intimidation, and violence, the polls were on the whole, free and fair, and far better than previous elections, which involved mass intimidation, boycotts, suicide bomb blasts, and assassinations. Many feared this time that the Rajapakse family had too much at stake to lose, and would use the military and dirty tricks to arm-wrestle a victory or even launch a coup d’ êtat. For whatever reason, this did not happen. Instead, Mahinda Rajapakse graciously accepted defeat and left office, allowing for a peaceful transfer of power.

Fourth, although Sri Lanka’s executive presidency, modeled on the French fifth republic, is constitutionally very powerful, President Maithripala Sirisena’s own political authority is fragile and weak. Having recently defected from the party he belonged to for his entire career, Sirisena is a floating politician without a party base, and with no political machinery at his disposal. He is beholden to his newly appointed prime minister, Ranil Wickramasinghe who occupies a constitutionally weaker position. But as leader of the United National Party (UNP), Wickramasinghe actually has a functioning party machine, competent ministers in waiting, and a few remaining MPs. As such, it is the prime minister and not the president who is de facto in charge, and who is taking steps to form a cabinet, negotiate with allies, and make key appointments in the coming days. The dynamics of this reversed relationship between the president and prime minister will be important to watch in the coming months.

Fifth, Sirisena was the common candidate backed by a disparate group of parties united only by their opposition to Rajapakse. The pro-business United National Party (UNP), the Sinhala nationalist Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU), and the quasi-Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) have some common forward-looking agenda items in reversing the institutional abuses of the Rajapakse period. But beyond that they share little. It is unlikely that the JVP will support any of the UNP’s market reforms, just as the JHU will reject concessions to the minorities. In any event, this arrangement remains transitory, and no major initiative can happen until a new parliament is elected, and until power at the apex is re-negotiated on the basis of parliamentary arithmetic.

Sixth, the prospects for political reform, accountability and reconciliation to address the legacy of war and ethnic conflict are greater now. But substantive change will be slow, controversial, and encounter increasing political resistance both within and without. Rajapakse made painfully little progress in this regard over the last five years since the end of the war. Indeed he sought to postpone, undermine, and bypass this agenda entirely, preferring instead the bricks and mortar of economic development. The north-east of Sri Lanka still has an overwhelming military presence, and the civilian population has for long been subject to an oppressive regime of surveillance and control. Maithripala Sirisena and many in his campaign retinue have made the right noises about reconciliation and greater sensitivity to the needs of minorities. But he has also ruled out a withdrawal of the military from the north and it is unlikely he will want to provoke the military establishment or fuel a Sinhala nationalist backlash. Previous attempts to settle the Tamil question by Sinhalese leaders have led to the assassination of a prime minister (1959), violent insurrection (1987-89), and election defeat (2004). Even if the new leadership summon up the personal courage to risk everything and try yet again, it is far from clear that they will have the political strength to push it through.

Seventh, Sri Lanka’s international relations with India, the US, Japan, and Europe will experience a ‘dead-cat bounce’ from the extended collapse of the last decade. As with the reconciliation agenda internally with the Tamils, the simple fact of Rajapakse’s departure will itself help to release much of the accumulated tension, mistrust, and ill-will of the past. For this reason, there may paradoxically be much less that is asked of this government in terms of delivering progress on human rights, accountability, and media freedom. The big elephant in the room of course is the war crimes issue. The threat that Sri Lanka’s military and political leaders would be dragged through an international investigation was for long the maximalist pressure tactic used to induce the Rajapakse regime to accept ethnic power-sharing concessions. But with Rajapakse out of the way, it seems unlikely that India or the US will want to punish and pressure Sri Lanka in quite the same way; more so if the new government reverses the recent tilt towards China and reorients itself geo-politically back towards an India-US-Europe axis.

Eighth, and finally, we have not seen the last of the Rajapakses. The new president is weak and can be weakened further by a hostile parliament. The Rajapakse clan has numerous other aspirants, remains popular, wields considerable influence, and has a strong domestic brand name associated with the civil war victory. They will be waiting in the wings for an opportunity to return to power.

This article originally appeared 11th January 2015 on Firstpost.com.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Dr. Rajesh Venugopal is Assistant Professor at the London School of Economics. His research is on the political sociology of ethnic conflict, particularly on the interface of nationalism and development in Sri Lanka and South Asia. Follow him on twitter at @rajeshvenugopal.

Dr. Rajesh Venugopal is Assistant Professor at the London School of Economics. His research is on the political sociology of ethnic conflict, particularly on the interface of nationalism and development in Sri Lanka and South Asia. Follow him on twitter at @rajeshvenugopal.

Given that the Presidential election is a one-person-one-vote ballot, I think it is not so significant to analyse the ethnic support to Maithripala Sirisena purely on geography, as many commentators have done. So glad to see you point out that Rajapakse did lose many of his core Sinhala Buddhist voters. One could doubt though the relative fairness of this election – given that in the run up to the election the Rajapakse campaign used and abused state power, put out false propaganda via the state media (and via private telecommunication channels) and inhibited the Sirisena campaign from accessing public spaces. It is also now clear that it is false to have assumed that “Mahinda Rajapakse graciously accepted defeat and left office”. What needs to be celebrated is the fact that the military and senior public officials declined to accept orders from Rajapakse in the face of the overwhelming peoples’ choice and that it was that that forced his departure. His subsequent speeches in his home town in Medamulana suggests you are right, that Sri Lanka has not seen the last of him: and that he has no interest in addressing questions of integration but would come back on an even stronger majoritarian platform.