Recent research illustrates the immediate positive effects of transit networks in India on rural employment, manufacturing growth and so on. Gaurav Khanna focuses on the long-term impact of national highways and shows that they gave rise to a dynamic pattern of regional development over time.

Recent research illustrates the immediate positive effects of transit networks in India on rural employment, manufacturing growth and so on. Gaurav Khanna focuses on the long-term impact of national highways and shows that they gave rise to a dynamic pattern of regional development over time.

One of the puzzles of the rapid but inequitable growth of the Indian economy has been the faster growth of some regions as compared to others. Why did some regions do better than others? One piece of this puzzle lies with the access to better infrastructure like transit networks.

Roads and railways can aid development by facilitating trade and migration, and reducing barriers to the spread of new technologies. A recently growing body of research looks at how rural roads under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) may increase rural employment (Asher and Novosad 2015), or how the Golden Quadrilateral2 upgrades led to greater entry of manufacturing firms (Kerr et al. 2014, Asturias et al. 2015). While these results illustrate the immediate effects of transit networks, it is of crucial importance to study the long-term impact as well. In this column, I show that these networks give rise to a dynamic pattern of spatial development over the long term and that the immediate effects may in fact massively underestimate just how important roads are (Khanna 2014).

Isolating the impact of transit networks on development

Isolating the impact of transit systems is challenging for many reasons. Richer regions have more funds to build better roads and upgrade their infrastructure. It is also possible that roads are built in regions that are expected to develop. Hence, looking at development in regions along the roads does not tell us that roads caused development since it may have well been that development leads to more roads. Furthermore, roads are more likely to be built in suitable terrain or places with lesser land acquisition issues, leading to other complications in identifying a causal link between roads and development. It is therefore essential to get around these issues when studying the impacts of roads.

The highway system in India first came up to connect the four major metros – Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai – also known as the Golden Quadrilateral. The shortest path between these metros would be straight-lines between them. However, the highways follow a path determined by the terrain of the land and possibly the development of regions they pass through. The straight lines are merely a geometric construct and therefore, completely independent of factors such as terrain, land acquisition issues or the level of development of regions, which impact the actual placement of highways. Thus, the straight lines can be used as proxies for the highways in order to isolate the effect of roads on development, from the other factors mentioned above. Therefore, the straight lines can serve as indicators for these transit networks, that can help isolate the effect of roads on development from the above mentioned contaminating factors.

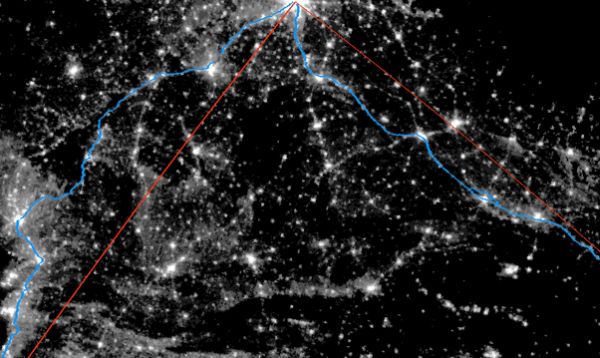

Another issue is one of data. To understand the regional impact, it is necessary to have reliable data at the sub-regional level. However, this is very hard to obtain because of the absence of good disaggregated district-level GDP (Gross Domestic Product) numbers. To accurately measure overall economic activity, one can use satellite data on night-time light density which does a great job of predicting regional income in the absence of good disaggregated GDP numbers (Henderson, Storeygard and Weil 2012). An example of this satellite data is shown in Figure 1, which displays a zoomed in aerial picture of Delhi (at the top-centre of the picture) and its surrounding regions. These lights, therefore, capture overall economic activity in a region down to an extremely minute geographic level, and present a striking visual of where development is taking place. I combine this satellite light-density data with geographic data on roads and the straight-line paths between metros to study the impact of these networks on regional development, and identify a causal link between these them, if one exists.

Figure 1. Light density and national highways

A dynamic pattern of regional development over time

Figure 1 shows a snapshot of the northern portion of the country, with the national highways radiating out of Delhi (the blue lines). It also shows the straight lines (in red) that connect Delhi to Mumbai and Kolkata. One can trace out the major roads by just looking at the night-time light density. Small and large towns crop up on the major routes, not just along the blue lines (national highway) but also along other major roads that can be traced out in that Figure 1.

Today, if we compare regions along these highways with those slightly further away, we see almost no difference in the level of economic activity, and this (non) result is similar to what has been found in other parts of the world (Fogel 1964, Banerjee et al. 2010). This may lead to the somewhat counterintuitive conclusion that roads do not appear to affect development since even areas far away from roads seem to have as much economic activity as those closer to roads. However, this snapshot misses a deeper understanding of the true impact of roads on development since it ignores the dynamic patterns in the spread of economic activity. Using the data gathered for this research, if we compare these regions in the early 1990s, the regions along transit networks are a lot richer than those further away. Over time, however, the regions further away start catching up, and today they have nearly comparable levels of development as those along the roads. And it is this salient fact often ignored by researchers – that transit networks do cause development, and in a more staggered fashion than was previously thought. Development first takes places along the transit networks and then slowly spreads spatially even to regions slightly farther away.

In 1992, a 1% increase in distance from the road led to a 0.15% decrease in regional GDP. By 2012, however, this decrease was only 0.06%. If we were to only look at the 2012 numbers as a snapshot, we may say roads don’t matter. This is because as economic activity spills over to regions further away, distance from the road seems to matter lesser and lesser. These spillovers across regions can be quantified as well – a 1% increase in light-density (and hence, economic activity/ development) in a region close to the road, leads to about a 0.8% increase in its neighbouring region’s light-density. The impact of the road, is therefore, not only felt on regions it passes through but even on regions further away via these spillovers. Once neighbouring regions catch-up, then comparing areas along roads to their neighbours may make it seem like roads don’t matter, when in fact they matter even more than before since there are spillovers in activity from one region to its neighbour.

Using this data, one can then trace out the entire pattern of regional development. In the two decades, since the early 1990s, regions along the transit networks are the first to develop, after which activity spreads to their neighbours, and then their neighbours’ neighbours. Thus, the path taken by the road determines the geographic spread of economic activity across the country.

In Figure 2, one can delineate the spread of activity along the Mumbai-Chennai highway during 1992-2008. In this picture, light density has been converted to a dark green (low density) to yellow (medium density) to red (high density) scale. As early as 1992, one can see areas along the national highway (the thin blue-line) seem to be more developed than those further away. This is especially true for regions closer to Mumbai, and then the portion between Bangalore and Chennai. By 1997, the region on the road between Mumbai and Bangalore develops, and activity spreads to regions adjacent to the places that were rich in 1992, highlighting the pattern of spillovers. This spread becomes even more prominent by 2003 when the neighbours’ neighbours become richer. By 2008, the dissipation is almost complete and economic activity has spread to most remaining areas.

Figure 2. Spread of activity along the Mumbai-Chennai highway

Investment in large infrastructure projects likely to have positive regional spill overs

My research highlights the crucial role played by large infrastructure projects. Transits networks help encourage economic activity not just between the large cities, but also among the small towns they happen to connect on the way. And this activity spreads from one district to the next, allowing poorer regions to catch up with the rich. Access to better infrastructure, therefore, can have significantly large impacts on the overall development of the region. The next stage in policy should then include upgrading the transit network infrastructure, and connecting villages to these highway-networks under schemes like the PMGSY.

This article originally appeared on the Ideas for India blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Gaurav Khanna is a Ph.D. candidate in economics at the University of Michigan with interests in development economics, labour economics and political economy. His most recent project studies the impact of affirmative action policies in India, and their effects on incentives for minority-group students. He also has projects that look at how the Indian government uses public-works programmes to tackle socio-political issues like insurgency-related violence. Prior to starting his Ph.D., Mr. Khanna worked at the World Bank’s Poverty Reduction Unit, and studied the effects of the financial crisis on unemployment and wages across many different countries. He received his M.Sc. in Development Economics from Oxford University, and his B.A. in Economics from Delhi University.

Gaurav Khanna is a Ph.D. candidate in economics at the University of Michigan with interests in development economics, labour economics and political economy. His most recent project studies the impact of affirmative action policies in India, and their effects on incentives for minority-group students. He also has projects that look at how the Indian government uses public-works programmes to tackle socio-political issues like insurgency-related violence. Prior to starting his Ph.D., Mr. Khanna worked at the World Bank’s Poverty Reduction Unit, and studied the effects of the financial crisis on unemployment and wages across many different countries. He received his M.Sc. in Development Economics from Oxford University, and his B.A. in Economics from Delhi University.

1 Comments