The Murty Classical Library of India aims to make historic texts from India available in English. Pragya Tiwari celebrates the venture, highlighting its importance at a time when Hindu nationalist groups are rewriting historical narratives to imply India has a single cultural identity rooted in religion.

The Murty Classical Library of India aims to make historic texts from India available in English. Pragya Tiwari celebrates the venture, highlighting its importance at a time when Hindu nationalist groups are rewriting historical narratives to imply India has a single cultural identity rooted in religion.

As a doctoral student at Harvard, computer scientist Rohan Murty began to take graduate courses in ancient India studies and was surprised by the range and depth of the intellectual work from that era. It was around the same time that classicist Sheldon Pollock was looking for funding for a new library of Indic texts. The two met through common friends and set up the Murty Classical Library of India (MCLI) with a gift of $5.2 million from Murty.

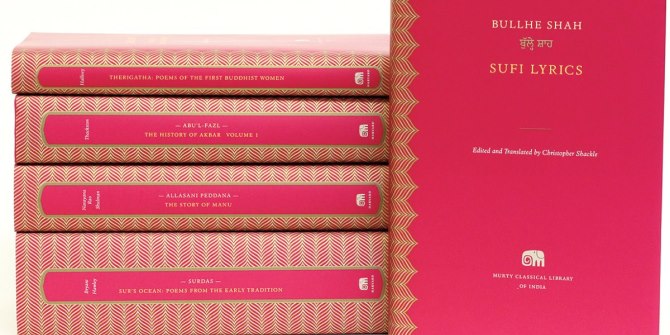

In the mould of the Loeb Classical Library of Greek and Latin texts, the MCLI aims to publish over 500 Indic literary texts (to be released in installments of 4 or 5 every year), created in the last two millennia- before 1800, translated into modern English. The idea is simple but powerful because it promises more than just reading pleasure. The first installment from the library consists of five beautifully produced volumes. One of them is a book of Bullhe Shah’s Sufi poems.

Bullhe Shah was a mystic and poet from 18th century Punjab that a lot of Indians have heard of but very few have read. Bullha ki janan main kaun (‘Bullha, what do I know about who I am?’), begins the refrain of one of his best known lyrics. While the question might shadow the existence of every human being at some level, it is particularly central to Indian cultural identity today.

Last year the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a right-wing Hindu majoritarian party formed the government at the centre with its allies, headed by a Prime Minister accused of complicity in the communal clashes in Gujarat in 2002 when he was Chief Minister. Predictably, any number of regressive majoritarian groups with right-wing social agenda (strengthened directly or indirectly by BJP rule) have come crawling out of the woodwork. Attempts are being made to ‘re-convert’ Muslims to Hinduism, prevent inter-religious marriages that are labeled ‘love jihad’, rewrite history to give greater prominence to Hindu icons, politicise languages and, of course, stifle narratives that run counter to this lunatic fringe.

At the root of it is the core agenda of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) – the BJP’s parent organisation – to organise the society such that it owes allegiance to their idea of an ancient Hindu nation state that is mostly a figment of a rather wanting imagination. The singular and uniform cultural identity rooted in religion that they seek to impose never existed. What did exist for many millennia instead was an impossibly rich and diverse civilisation that defies any attempt to examine it through the limited prism of strict religious identities.

The only way to access this past is through the literature, poetry and records of its times. Fortunately for us, thousands of texts in several languages do exist. Unfortunately we have direct access to very few of them – partly because they are out of print and partly because no Indian can read all the different languages spoken in this country currently, let alone ancient languages that are no longer in use.

It is in this context that the MCLI’s translation of Bullhe Shah’s Sufi lyrics become more valuable than ever. Drawing from the Sufi tradition of mysticism, Bullhe Shah wrote poetry that is sharp, simple and immortal. His verses question strictures of organised religion and societal norms. They are beautiful paeans to romantic and mystical love underpinned by rich spiritual philosophy.

Other books in the series include The Story of Manu by Allasani Peddana, translated from Telugu; The History of Akbar, Volume 1 by Abu’l Fazal, translated from Persian; Therigatha: Poems of The First Buddhist Women, translated from Pali and Sur’s Ocean by Surdas, translated from Braj Bhasha.

Telugu poetry traditions existed for at least half a millennia before Peddana but he called himself the creator of Telugu poetry because he created a dramatically new idiom- stylistically and thematically a new genre of Telugu poetry. The Story of Manu, translated for the first time into any language, gives a much wider readership access to his masterful, lyrical wordsmithery. It also affords, through its plot, a rare glimpse into the political and religious philosophy of its times. The story revolves around the life of Svarochisha Manu, a sort of prototype of the first human being who ruled over the previous cosmic age and explores the idea of what it means to be human through the relationships between reality and illusion, nature and evolution, desire, humanity and knowledge. Peddana was a close associate of King Krishnadevaraya who ruled the Vijayanagara empire at its height. The text through its meditation on what makes an ideal king also becomes a statement of the moral and creative aspirations of the kingdom.

The History of Akbar, Volume 1 – not history in the strictest terms but part philosophy, part history and part biography- also explores the idea of the ideal ruler by apotheosizing Akbar. He is cast as an ideal man based on the Sufi understanding of the concept. Fazal drew on records and other pre-existing historical texts to trace Akbar’s genealogy and chronicle 16th century India. At a time when Hindutva historians are eager to distort the history of Muslim invasions in order to deepen religious cleavages and consolidate vote banks, Fazal’s elaboration of Akbar’s legacy as a tolerant Muslim ruler of a non-Muslim majority is an important reminder of how Indian society has evolved. His policy of sulh-i-kul, or universal concord, was rooted in both ideological and political concerns and still has lessons to offer for students of Indian politics.

Sur’s Ocean containing 433 early poems by the finest poet of Braj Bhasha, Surdas, refashioned the mythology of the Hindu deity Krishna and his lover Radha. These moving, elegant and accessible poems were hugely popular in their times spawning an oral tradition so vibrant that poems continued to be composed in the tradition started by Sur, under his name, by several other poets as well. By the 19th century over 10,000 such poems were documented. The devotion at the heart of this poetry is a form of the Bhakti tradition that had a lot in common with the Sufism Fazal and Bullhe Shah subscribed to.

The other volume of religious poetry in the collection, Therigatha: Poems of The First Buddhist Women is marvellous not only in that it is an archive of poetry in a language no longer in use but also in that it is the world’s first known collection of literary work by women– documenting the aspirations and achievements of women from nearly two thousand years ago. These poems or utterances that introduce their readers to the practice and intricacies of Buddhism also serve as a testament to the multiplicity of faith and cultural experience in the Indian sub-continent.

All five books are from different time periods, different geographical areas and vastly different in form and subject matter and yet there are common threads that run through them. To that extent they are also a metaphor for the elusive Indian cultural identity.

The books in the Murty collection have excellent introductory notes on the text, its context, author, themes, form and the translation itself. The original text, in the original script, appears alongside the translation. But for all their simplicity, the process of creating these volumes has been far from easy. Creating fonts for Indic scripts that did not exist, finding translators fluent in both English and the language of the texts and sourcing the texts themselves have all been uphill tasks. General Editor of the series, Sheldon Pollock, talks about the challenges of studying Indic texts in this interview at length. He also speaks eloquently here about the attempt to politicise the past and deny it its true splendour.

The Murty Classical Library is an assault against cliché and bigotry. But more significantly it is an opportunity for us to know where we come from and move closer to answering Bullha’s impossible question- Ki janan main kaun?

Find out more about the Murty Classical Library at www.murtylibrary.com.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Pragya Tiwari is a journalist pursuing an Executive Masters in Public Administration from LSE. She lives between Delhi and London and tweets as @PragyaTiwari.

Pragya Tiwari is a journalist pursuing an Executive Masters in Public Administration from LSE. She lives between Delhi and London and tweets as @PragyaTiwari.

1 Comments