As the debate around net neutrality in India shows no sign of abating, Amandeep Singh and Nikhil George take a closer look at the Save the Internet Campaign and discuss its role in India’s regulatory governance space.

As the debate around net neutrality in India shows no sign of abating, Amandeep Singh and Nikhil George take a closer look at the Save the Internet Campaign and discuss its role in India’s regulatory governance space.

If you have been following the news over the last few days, it is unlikely that you’ve missed the steady stream of reports and commentary on net neutrality. If you are reading this on an electronic device in India, it is also highly likely that you’ve received a request to spare some time towards a lofty goal, namely to save the Internet and preserve net neutrality. You are expected to contribute to this endeavor by submitting a response to the telecom regulator, TRAI’s, consultation paper on a regulatory framework for over-the-top services. The idealism and enthusiasm on display pushed us to download the 118-page TRAI paper and the 4000 word response that over a million people sent for TRAI’s consideration.

This is most uncommon; regulators have in the past brought out consultation papers and given reasoned orders on several important resources and services that we rely on – from bank deposits to allocating water among competing uses. Although these consultation papers and orders have always been carefully read and discussed – albeit almost always amongst people closely associated with the particular sector – discussions on them have seldom featured in popular media, let alone motivating over a lakh people to send-in 20-page responses. Are we more concerned about our access to the Internet in the future than say our access to water? Or is it that a lot more people amongst us understand and follow regulatory deliberations in the telecom and Internet sectors unlike other sectors?

The likely reason is neither. In recent years, the creative use of social media platforms has become a key means for assembling protest and expressing dissatisfaction, particularly for India’s urban middle class. The leaders of such protests leverage the unrivalled speed, reach and cost effectiveness of the medium to garner support for a cause. When a cause gathers sufficient support on the social media platform it gets featured and discussed on television and print media, giving it even more thrust. Conversations on net neutrality violations in the Indian context began appearing on the Internet after the Facebook-led Internet.org became available for users in India (in February 2015 through the Reliance mobile network). When TRAI uploaded a consultation paper on the subject inviting responses, activists quickly styled an Indian version of the ‘Save the Internet’ campaign, along the lines of Freepress’s ‘Save the Internet’ campaign. What followed is well-known and a timeline of this widely successful campaign is available here. Here, we take a closer look at the campaign and discuss its role in India’s regulatory governance space.

There is evidence that democratic governments are often short-sighted when drawing up policies, thereby putting future interests at risk. This is because democratic governments need to be responsive to its electorate, a diverse entity which is often impatient, lacks the time to understand complex policy issues, and has a clear preference for the present over future. Several mechanisms have been evolved to guard against a government’s policy short-sightedness. One such mechanism involves transferring part of governmental decision making to a body of independent experts, known as an independent regulator. The decisions made by independent regulators draw their legitimacy through their technical capacity and procedural transparency. India now has independent regulators for financial services, electricity and telecom sectors amongst others.

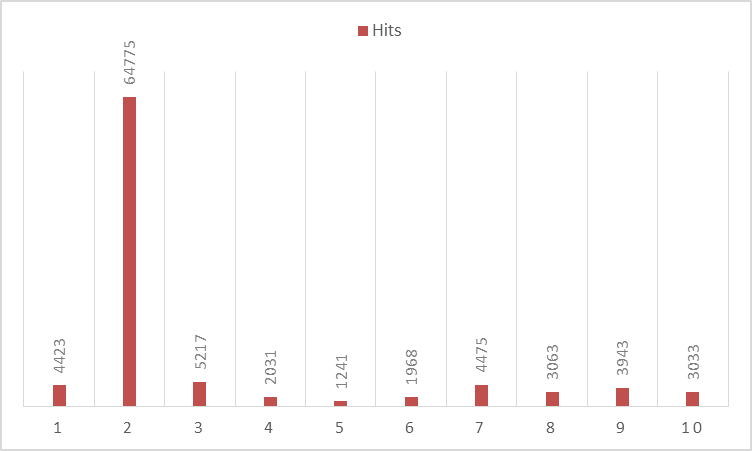

However, regulatory institutions come with their own set of challenges, concerning (but not limited to): their design, representativeness, objectives, and accountability. Ironically, despite clamour of regulatory capture, it is because of the direct forms of accountability that an independent regulator is subject to that has resulted in the discourse on net neutrality among a wide set of audience. Through its open consultative process, providing reasoned orders, and having a redress mechanism, its decision-making process is open to scrutiny by civil society, industry and technical experts. But, although its consultative paper on ‘Regulatory Framework for Over-the-Top (OTT) services’ has been subjected to voice-based accountability, it may not be true for other such decision-making by regulators at large. The figure below starkly illustrates the disproportionate amount of attention the paper has received with a total number of download hits at 64,775 as of 5 May; the second most downloaded document in the last ten released consultation papers received a mere 5,217 hits. It is of great interest to decode the factors that have contributed towards the appeal of this particular consultative paper, in order to understand the accountability (or the lack of) of regulatory bodies.

The scale of such a response is partly the result of TRAI’s framing of the discourse, citing: the loss of revenue for Telecom companies/Internet Service Providers’ (ISPs) traditional business from for-profit content providers, the lack of compensation to ISPs for investments in infrastructure such as towers and fibre optic cables, and the regulatory imbalance between service and content providers. Where proponents of net neutrality argue for equitable treatment of all data packets, regardless of origin or purpose, the tone of TRAIs consultative paper suggests regulatory oversight is increasingly becoming unfeasible. Also, TRAI’s contemplation of a licencing regime for OTT applications is perhaps symptomatic of the underlying mistrust of the potentially disruptive nature of such new forms of services. Perhaps a useful exercise is to understand to what extent the existing regulatory environment – particularly the Information Technology Act of 2008, anti-trust regimes, and privacy laws – address TRAI’s concerns. For example, while many telcos have applied for payment banking licenses, does this apply for OTT applications as well? What are the possible unintended repercussions of regulating apps originating outside India – say, retaliatory measures on Indian apps and services?

It is important to understand that network neutrality lies on a continuum, and therefore the degree to which its principles are violated are context-specific. For example, in India, the discourse on net neutrality has ignored data download limits imposed on fixed broadband subscribers of ‘unlimited’ data plans once a predefined cap is reached. Although the imposing of such caps is widely accepted, in the United States such practices are perceived as a violation of net neutrality. Similarly, the Federal Communications Commission in the US is silent on the issue of zero-rating – arguably the focal point of contention in India – a practice by mobile operators to allow access to certain (partnered) sites without charging customers for data usage. Critics argue that zero-rated services give a free hand to access-providers to ‘nudge’ consumers towards established content-providers, to the detriment of the ‘next Facebook’. Others have called for a more transparent process for content providers to obtain zero-rating so that it does not favour the ISP’s own or partners’ OTT services. The debate also throws up interesting questions on whether some form of connectivity to the Internet is more important than ensuring a level playing field for content providers? Should emergency and health services be given priority and better speeds while managing congestion, whilst spam and criminal traffic is slowed or stopped all together? For example, should there be zero-rating for applications such as Google’s Person Finder in cases of disasters? Who decides what constitutes as exceptions to the open Internet? While some would want TRAI to take a clear position, others have argued for the status quo, i.e. relying on the competition among the telecom companies/ISPs to bring maximum benefits to maximum customers.

Also, it is important to try and understand the representativeness of the campaign.The makeup of Indian Internet users is such that wireless subscribers far exceed fixed Internet subscribers. Whereas the debate on net neutrality in the United States was dominated by the threats to video streaming services such as YouTube and Netflix – primarily consumed by fixed broadband users – in India, it is the implications of net neutrality on mobile users that has spurred the discussion. According to TRAI’s Telecom Subscription Data (on 28 February), broadband subscribers – defined as 512 kbps or greater download speeds – totalled 81.48 and 15.45 million for mobile and wired users respectively (although it is worth noting the number of broadband users is expected to be greater given multiple users to each fixed subscription, institutional subscriptions, and those with access speeds less than 512 kbps). With a mobile subscriber base of more than 960 million – 557 in urban and 403 in rural settlements – the online campaign is likely silent on the views of millions currently without access to any forms of Internet access.

What is undeniably the most fascinating aspect of this ongoing debate is the manner in which the topic has caught the imagination of the public. The means of displaying disapproval has ranged from downgrading or deleting Facebook and Flipkart applications, subjecting TRAI’s website to a denial of service attack, and uploading videos outlining the evils of violating net neutrality. In his analysis of the middle class’s participation in the Anna Hazare campaign, Vinay Sitapati identified these strategies with a group he described as ‘India Shining’ – critical of politics and governmental inefficiencies but admirers of the private sector efficiency. Here while the methods of assembly and protest are similar, the targets — telecom companies (most of who are in the private sector) and an independent regulator (who espouses a technical approach to its functioning) are very different. In this post we have presented a brief narrative both of the campaign and the surrounding public debate.

As the Internet develops in India, will it stick to the campaigners’ idea of neutrality as it works towards building a digital India? One vs a million; would the scale of the campaign affect TRAI’s informed view on the matter? These more interesting and important questions on the topic are underexplored. We hope the high profile of the debate will encourage researchers to address fill these gaps.

Cover image credit: flickr/Steve Rhodes CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the India at LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Nikhil George is a research associate at the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi. Before joining CPR, he worked with the Centre for Energy, Environment, Urban Governance & Infrastructure Development at the Administrative Staff College of India, Hyderabad. He holds an MSc from the TATA Institute of Social Sciences and a BTech from the School of Engineering, CUSAT. He is interested in a wide range of issues including participatory planning, service delivery, and regulatory processes.

Nikhil George is a research associate at the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi. Before joining CPR, he worked with the Centre for Energy, Environment, Urban Governance & Infrastructure Development at the Administrative Staff College of India, Hyderabad. He holds an MSc from the TATA Institute of Social Sciences and a BTech from the School of Engineering, CUSAT. He is interested in a wide range of issues including participatory planning, service delivery, and regulatory processes.

Amandeep Singh is a research assistant at CPR. He researches the relationships between sanitation technologies, and the social contexts in which these are embedded. He holds an MSc in Environmental Policy and Regulation, and a BSc in Environmental Policy with Economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Amandeep Singh is a research assistant at CPR. He researches the relationships between sanitation technologies, and the social contexts in which these are embedded. He holds an MSc in Environmental Policy and Regulation, and a BSc in Environmental Policy with Economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science.