Cultural affinities can be created and cultivated to great effect in South-South Co-operation. Pooja Jain draws on the case study of India and Senegal to highlight how cultural links developed over time have fed into the flourishing economic partnership the two countries enjoy today.

Studying the political economy of cultural exchanges between India and Senegal seems counterintuitive at first sight. Language is a modicum of exchange and the linguistic profiles of the two countries make exchanges of such nature unlikely or difficult to conceive. That said, it is the very absence of apparent historical and linguistic similarities and connections that make India and Senegal an intriguing case for exploring cultural links. As it happens, French is one of the most widely-spoken languages among Indian diplomats. So, paradoxically, at a diplomatic level language is far from being a barrier. The interest in the search for cultural links between the two is also evoked by the increasing vigour of economic inter-reliance between the two countries. India is one of the leading importers of phosphates from Senegal, which is a prerequisite for maintain a steady supply of fertilisers for India’s farm sector. On the other hand, Senegal is an important beneficiary of concessional funding from India for projects with a ‘social utility’ factor for instance, urban transport and agriculture. In this article we examine the creation, commodification and appropriation of cultural affinities in South-South Co-operation (SSC) using the case study of India and Senegal. With soft power and nation-branding as the conceptual base, we elaborate the case study with appropriate evidence.

Speaking of India and Senegal, the two countries share a bond within the larger framework of South-South relations. There is evidence of simultaneous occurrences in the history of India and Senegal, which assume importance when building a contemporary narrative of their relations. Indeed, the West African region and India witnessed parallel movements in their struggles for independence. The historian Mamadou Diouf has mentioned the similarities in the narratives of Cheikh Anta Diop in the 1950s and the Indian nationalist historians in the 1920s and 1930s. The two refused passive subjugation to the colonial production of knowledge, which was embedded in power. These ideas still resonate as the founding principles of SSC. Since independence, the two countries have shared a common political culture in the form of democracy, which constitutes an important dimension of their current relations. It is not surprising that Senegal is the location of India’s EXIM (Export-Import) Bank branch for West Africa. Indeed, Senegal playing host to international organisations is not exclusive to India. Senegal’s engagement with multiple partners is part of its larger foreign policy.

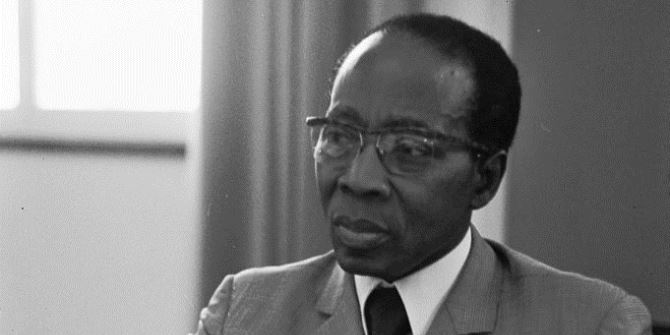

In the more recent past, the early 1980s were an important period in the history of independent India and Senegal. In 1982 Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first President of Senegal was conferred the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for international understanding. Following his visit to Chennai (then Madras), Senghor penned poems, struck by the physical resemblance between South Indians and Senegalese. During his tenure as President, Senghor pushed for the study of linguistic similarities between native West African and Indian languages. Senghor often cited Rabindranath Tagore in his speeches. Although, the importance of these elements of Indo-Senegalese links should not be over-stated, in light of the larger narrative on India-Africa relations, they are lost threads which need to be picked up. It was also during this period (early 1980s) that India and Senegal fortified their trade relations in the import of phosphates from Senegal to India.

In the contemporary context, it is popular culture that has become a connecting bridge between the two countries. The demography of the two countries is marked by a generation of aspirational youth. The information technology sector is symbolic of ambition and youth culture in India and in Senegal. These symbols have been the raison d’être for Indian private companies like NIIT locating in Senegal and the respective surge in economic ties between the two countries. The domestic emphasis on the telecommunications and information technology sector in Senegal is also the reason behind Dakar being the satellite hub for the Pan Africa e-network. Cultural diplomacy is also gaining ground through the increasing presence of African cultural fests organised on the side lines of economic and business meets. Senegal has been an active participant in these events. Furthermore, the surge in economic ties has witnessed a revival of historical and cultural links. This has put the Siddi Goma in the limelight. Siddi Goma in India are a mainly Sufi tribal community of African origin. They participated in the Black Arts Festival in Dakar in December 2010. The Siddis represent a blend of African dance and music with Indian Sufism, Sufism being widespread in Senegal.

Popular visual art and media have their own trajectories which pave the way for creating an affable and benign narrative of shared political and economic interests between the two countries. TV soaps aired at prime time in Senegal along with Bollywood cinema have become a window to India. Here, the popularity of Indian films and soap operas lies not in their ability to speak a universal modern language but in creating a cultural space through emotions, music and dance which transcends the dichotomies between the real and the fantastic and occidental and non-occidental. This niche occupied by Indian film is directly associated with the image of the country and not to a multinational production house. That said, a reciprocal phenomenon similar to the success of Indian visual arts culture in Senegal is yet to be witnessed in India. The popularity of the Senegalese singer Akon in Indian film industry is a notable exception but his success in India mirrors his success as a musician in the United States. Also, this ‘faceless’ dissemination of Indian cinema could take a more organised corporate garb associated with soft power and intertwined economic interests. For instance, recent news stories suggest that Nigeria succeeded in obtaining a line of credit from India for the development of its film industry Nollywood while also paving way for greater penetration of its Indian counterpart Bollywood. The lines of credit come with the condition that 75 per cent of material and service be sourced from India.

Meanwhile, only a handful of Indians reside in Senegal, approximately three hundred and eighty according to official figures. They are seen as a rotating diaspora who are in Senegal for mostly business interests. Indeed, the hospitality associated with Senegalese culture ‘Teranga’ is witnessed as a major incentive for people to stay. This is in spite of certain differences in ‘work culture’ arising from the labour laws influenced by the pre-colonial histories (English and French) of the countries. My interviews with Indians working in Senegal suggested that the labour market in Senegal was inflexible. Private company personnel were of the opinion that the Senegalese semi-skilled workforce was dexterous thanks to their experience in handling imported machinery. On the contrary, in India the Swadeshi or self-sufficiency movement along with import restrictions prevented the workforce from acquiring skills needed to work with imported machinery. In spite of these differences, references to popular culture become conversation starting points even between complete strangers hailing from these countries. The success of the Indian soap Vaidehi in Senegal has become indispensable to any conversation on Indo-Senegalese relations. During my interview with the Indian EXIM Bank representative in Dakar in January 2012 and his assistant from Senegal, one of the first common references they cited was the popularity of the aforementioned Indian soap opera in Senegal. The popularity of Indian culture becomes an introduction to other things Indian, including private companies looking for business interests. The positive image of the country gives a default trust benefit for starting economic partnerships. On the same lines, growing trade between the countries gives the impetus for an institutional boost to cultural relations. India and Senegal recently signed an executive programme for cultural cooperation.

We use the above case study to argue that contemporary economic and geopolitical interests drive a commodification and appropriation of culture where the boundaries between economics, cultural affinity and moral standing are blurred. This narrative of soft power and positive branding of the nation using the trio of culture, diplomacy and business soften the edges of a dominant self-seeking foreign policy. As it happens, this soft power narrative does not concur with the principles of SSC. Soft-power and nation-branding do not seek symmetry or equality in relations but the power to persuade and sell. On the other hand, the principles of mutual benefit and equality are a basis of SSC. Moreover, the success of soft power cannot be solely attributed to the nation that seeks to persuade. Its success depends on the receptivity and interests of the host nation as well. Indian companies can sell and sustain business in Senegal thanks to their strategies and also to the secure and receptive business, political and social environment Senegal provides. The intermingling of culture and economics could enhance people to people contact which is one of the bedrocks of the India-Africa partnership. Greater people to people contact could also open the relations between the two countries to an increased public interest and scrutiny. Most importantly, the violence faced by Africans in India could deal a huge blow to the imaging and projections of soft power by India. It is in practicing what is projected where Senegal supersedes the much bigger India. Senegal’s capacity to actually practice its very famous culture of hospitality ‘Teranga’ could provide the cue for longer lasting relations between India and Africa.

This article originally appeared on the Africa at LSE blog. This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Dr Pooja Jain is a Visiting Fellow at EHESS