The Handbook of Indian Defence Policy aims to provide an authoritative, compelling and comprehensive survey of India’s defence policy since it gained its independence in 1947. Raj Verma finds it an essential read for students, scholars and especially policymakers interested in the external and internal security challenges facing India, the numerous problems and limitations which might stymie India’s rise to great power status and possible solutions to overcome these.

Handbook of Indian Defence Policy: Themes, structures and doctrines. Edited by Harsh Pant. Routledge. 2016.

India has experienced rapid economic growth since it undertook economic reform and liberalisation in 1991. India grew at approximately six percent during 1991-2000, 8-9 percent during 2001-2010 and 7 percent from 2011-2015. During the same period, India became the third largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP) behind China and the US. In 2016, it is the fastest growing major economy in the world. Economic growth also translated into rapid growth in defence outlays/budget and defence expenditure, which in turn has led to expectations that India will be a major world power if not a super power in the near future. Some scholars have termed this phenomenon ‘India rising’ where others aver India has already ‘risen’. Accordingly India’s approach to fundamental issues of international security has come under greater scrutiny.

India has experienced rapid economic growth since it undertook economic reform and liberalisation in 1991. India grew at approximately six percent during 1991-2000, 8-9 percent during 2001-2010 and 7 percent from 2011-2015. During the same period, India became the third largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP) behind China and the US. In 2016, it is the fastest growing major economy in the world. Economic growth also translated into rapid growth in defence outlays/budget and defence expenditure, which in turn has led to expectations that India will be a major world power if not a super power in the near future. Some scholars have termed this phenomenon ‘India rising’ where others aver India has already ‘risen’. Accordingly India’s approach to fundamental issues of international security has come under greater scrutiny.

Handbook of Indian Defence Policy edited by Harsh Pant is opportune and an excellent attempt at providing an authoritative, compelling and comprehensive (albeit not exhaustive) survey of India’s defence policy since it gained its independence in 1947. The novelty of the handbook is that contributors straddle different careers, disciplines and countries: they include academics, practitioners, bureaucrats, officials from the Indian armed forces including a former service chief, a former head of Research & Analysis Wing (India’s external intelligence agency) and a journalist. The blend of academic and policy focus, opinions, debate and discussions offers a wide-ranging analysis of disparate aspects of India’s defence and security policy.

The handbook is structured thematically and divided into eight sections which each delve into different facets of India’s defence and security policy. Section One discusses the origins of the Indian armed forces during the East India Company and later during the British Raj. It highlights the interface and interaction between the military (especially the army) and the Indian society on the one hand and the executive including the bureaucracy and the military on the other. It also considers how and why the military is subservient to the civilian bureaucracy. It illustrates that India inherited a certain structure from the British Raj and even after almost seven decades, India is following more or less the same system. Only modest changes have been introduced, brought about due to severe crisis and not because of the alacrity, foresight and vision of the executive, the bureaucracy, the intelligentsia and the policymakers.

Section Two examines the important relationship between the Indian military and the country’s foreign policy. Contributors discuss the incongruity between the two and provide recommendations to overcome this. They also suggest that India’s defence diplomacy is erratic and it needs to be boosted significantly for India to achieve great power status. Section Eight focuses on nuclear weapons and space. Contributors discuss the evolution of the nuclear doctrine and how institutional, personal and ideological problems have and continue to mar India’s nuclear, missile and space programmes and hence its security. For instance, the military is completely absent in the decision making and formulation of India’s various doctrines – this privilege is enjoyed by politicians and bureaucrats in the Ministry of Defence who are not qualified to make the decisions.

Section Six discusses India’s internal security challenges with a focus on the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, the ‘Naxalite’ movement and the insurgencies in India’s restive and long neglected North East. It is important to note that the ‘Naxalite’ or ‘Maoist’ movement which has been linked to violence in almost 90 of the 540 odd districts in India – where the writ of the state fails in most cases – is considered the biggest internal security threat. This is despite the rise in Islamic fundamentalism in South Asia and the ideological, financial, political and military support provided to non-state actors and terrorist organisations by Pakistan, and to lesser extent by Bangladesh. The section highlights that insurgency, violence and the number of civilian and security forces deaths have decreased significantly in the North East.

Section Seven discusses the evolution of India’s national security doctrine and apparatus, and the infrastructure established to deal with the internal security challenges. It examines the evolution and role of central armed police forces (CAPF) such as Central Reserve Police Force, Border Security Force and Central Industrial Security Force; paramilitary organisations such as the Indo-Tibetan Border Police Force, Assam Rifles and Rashtriya Rifles; and the role of domestic and external intelligence agencies and the police in tackling India’s internal security challenges such as fighting insurgencies, terrorism and Islamic fundamentalism. It also discusses the achievements, issues, concerns and limitations facing the different organisations and provides remedies to overcome the problems. These chapters are extremely illuminating.

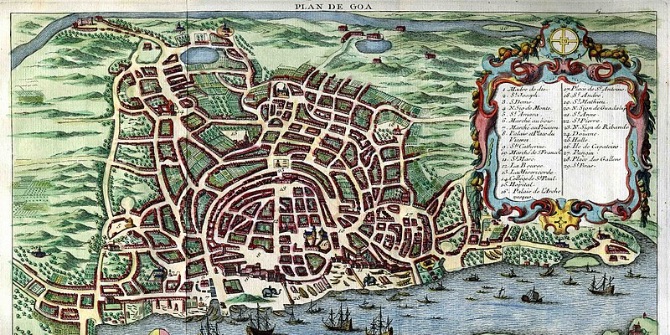

Section Three and Section Four discuss the evolution and history of the three armed forces namely the Army, the Navy and the Air Force, the evolution of their doctrines, the role they played in India’s wars during the British Raj and after India achieved independence in 1947 – with Pakistan and China – and in the integration of India especially in Hyderabad, Junagarh and Goa in 1961. The sections also discuss the numerous and multi-faceted problems and challenges faced by the three services and the solutions that have been explored. It also discusses the lack of coordination in operations, planning and integration of the three services, the rationale behind it and how this is affecting force multiplication and difficulties for India to meet its security challenges.

Section Five examines the ‘guns versus butter’ or defence versus development debate. It illustrates that India did not spend much on defence immediately after independence despite the war with Pakistan in 1948 and the growing threat from China after it annexed Tibet in 1951. Defence spending did increase after India lost to China in the border conflict in 1962 but declined again during the 1970s. In the 1980s military investment went up, with significant expenditure on the navy which had been ignored in previously, but it was only in the new millennium that defence spending has increased tremendously with emphasis on modernisation and procurement of advanced technology and equipment from the US, Russia, Israel and France among others. However, this push to modernise has not always progressed smoothly: contributors point to severe setbacks due to problems such as turf wars, bureaucratic politics, corruption, red tape, risk aversion, accountability and lack of force integration and planning.

Since the book is structured thematically and chronologically, there is a lot of overlap between sections. However, this is acceptable because they can be read as standalone chapters which deal comprehensively with the subject matter at hand. Certain additions would have helped to make the handbook more comprehensive. Firstly, a discussion India’s strategic culture which directly and indirectly influences India’s foreign policy, defence policy and its doctrines. This would have provided the conceptual map of how and why Indian policymakers, the armed forces and society think and act and how this affects security and defence policy and India’s ability and inability to meet certain security challenges – both internal and external. Secondly, cyber security is only given a cursory mention by a handful of contributors. Last but not the least, some analysis on the role (or lack of it) of India’s private sector enterprises in India’s defence acquisition, procurement and modernisation would be valuable.

The book also suffers from some factual errors. For instance, p.79 states that India is the third largest economy in the world. This is misleading as although it is the third largest economy in PPP terms, it lags in other rankings. P.107 states that China supported India during Kargil, when China actually remained diplomatically neutral during the conflict but sold weapons and equipment to Pakistan which helped the latter in the conflict (as discussed in Sumit Ganguly’s book Deadly Impasse: Indo-Pakistani Relations at the Dawn of a New Century). There are also a few editorial flaws such as Han Morgantheau (p.100) instead of Hans Morgenthau and reference to Mumbai attacks in 1998 rather than 2008 (p.54).

Despite these limitations, The Handbook of Indian Defence Policy is an essential read for students, scholars and especially policymakers who want to familiarise themselves with India’s defence and security policy, the external and internal security challenges facing India, the numerous problems and limitations which might stymie India’s rise to great power status and solutions to overcome the problems, and the role of interest groups and other domestic factors on India’s defence and security policy. Scholars are encouraged to have this as a core textbook on India’s defence policy and it is a must-have for libraries.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Dr Raj Verma is Assistant Professor of International Relations and Foreign Policy at the School of International and Public Affairs, Jilin University, China and Visiting Fellow, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, India. He is the author of India and China in Africa: A comparative perspective of the oil industry, Routledge and Series Editor of Routledge Series on India-China Studies.