Ahead of India @ 70, presented by Apollo Tyres Ltd, Harish Alagappa outlines the context of the second LSE India Summit and introduces the themes that will be discussed by academics, policymakers, activists and other experts on 29 and 30 March.

LSE’s historic relationship with India extends back to the earliest days of the university. It was the patronage of Sir Ratanji Tata, the grandfather of the contemporary industrialist Ratan N. Tata, which saw the establishment of the Department of Social Sciences at the LSE in 1912. Sir Ratanji’s motivation for this endowment echoed the university motto, Rerum cognoscere causas, or “to know the causes of things”. Over the course of the last 122 years, the London School of Economics has supported efforts by some of India’s greatest thinkers to know the causes of a diverse range of ‘things’, from understanding the socioeconomic mechanisms that lead to rampant poverty to the epistemology of formulating a law code and more, that applies to the second most populous country in the world.

India occupies just over half a percent of the world’s total land area, but is home to almost 20 per cent its population. It is a Petri dish of triumphs and tragedies and features samples of the most diverse range of religions, languages, ethnicities, and ideologies you are likely to find anywhere. After a successful inaugural Summit sponsored by Difficult Dialogues in 2016, the LSE India Summit 2017 takes place in the beating heart of India’s capital city, New Delhi. As independent India enters the 70th year since she emerged from the shackles of colonial rule, the Summit will investigate four core ideas that are shaping the future of this vibrant nation.

Corporate Social Responsibility

Perhaps the most important event in the last 70 years was the decision to lift regulations that effectively kept the Indian economy in a sealed bubble for most of the second half of the 20th century. Since economic liberalisation in 1991, the scope and range of foreign and private investments in the Indian economy has grown exponentially. As India’s potential as a global IT and business hub was harnessed, many large multinational corporations outsourced significant amounts of their workforce to India. Erstwhile sleepy university towns and villages on the periphery of major cities, such as Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Gurgaon, mushroomed into urban metropolises almost entirely dedicated to the IT and ITeS sector.

However, this growth has been far from uniform or inclusive. Indian cities are now a glaring example of what economist and diplomat John Kenneth Galbraith famously described as ‘an atmosphere of private opulence and public squalor.’ The LSE India Summit’s first theme explores a decision taken by the Indian government in 2013, which mandated companies that generate annual revenues above Rs.10 billion (approximately £ 120 million) to institute a minimum spend of 2% on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities. Panellists will discuss whether forcing philanthropy on the corporate sector is an effective mechanism to bridge the gap between private and public growth, and whether this act has had any impact on the social development and well-being of the common people.

Water security

Indians constitute one of the largest bodies of foreign students at the LSE. While many of them are studying questions that have emerged at the forefront of social, economic, and political thought in the aftermath of the information revolution that created the modern interconnected global economy, others are investigating problems that have persistently plagued human societies from the dawn of civilization. Water security is as much a primary concern to the well-being of Indians today as it was to our earliest ancestors. The LSE India Summit’s second major theme examines how water security is quietly dictating the agenda of inter-state relations within the Indian republic, and could be a potential flashpoint between India and Pakistan in the near future. The concept of Virtual Water looks at the actual embedded cost of goods and services, expressed as the amount of water utilised in their product life cycle. India is the world’s largest unwitting exporter of Virtual Water. As climate change and population growth threatens to make freshwater a rare natural resource, India’s massive Virtual Water deficit could form the core of future domestic and foreign policies.

Foreign policy

A 2015 report by Credit Suisse ranked India as the world’s fifth strongest military power, behind the United States, Russia, China, and Japan. The IMF and World Bank both rank India as the world’s seventh largest economy when measured by nominal GDP, and the world’s third largest economy when measured by GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP). After decades of atypical exile, one of the world’s oldest and biggest players is slowly reasserting itself in the great geopolitical game. The third theme of the LSE India Summit explores the strategies this new India has been enacting in its foreign policy gambits and whether they have the potential to reshape India into a global superpower.

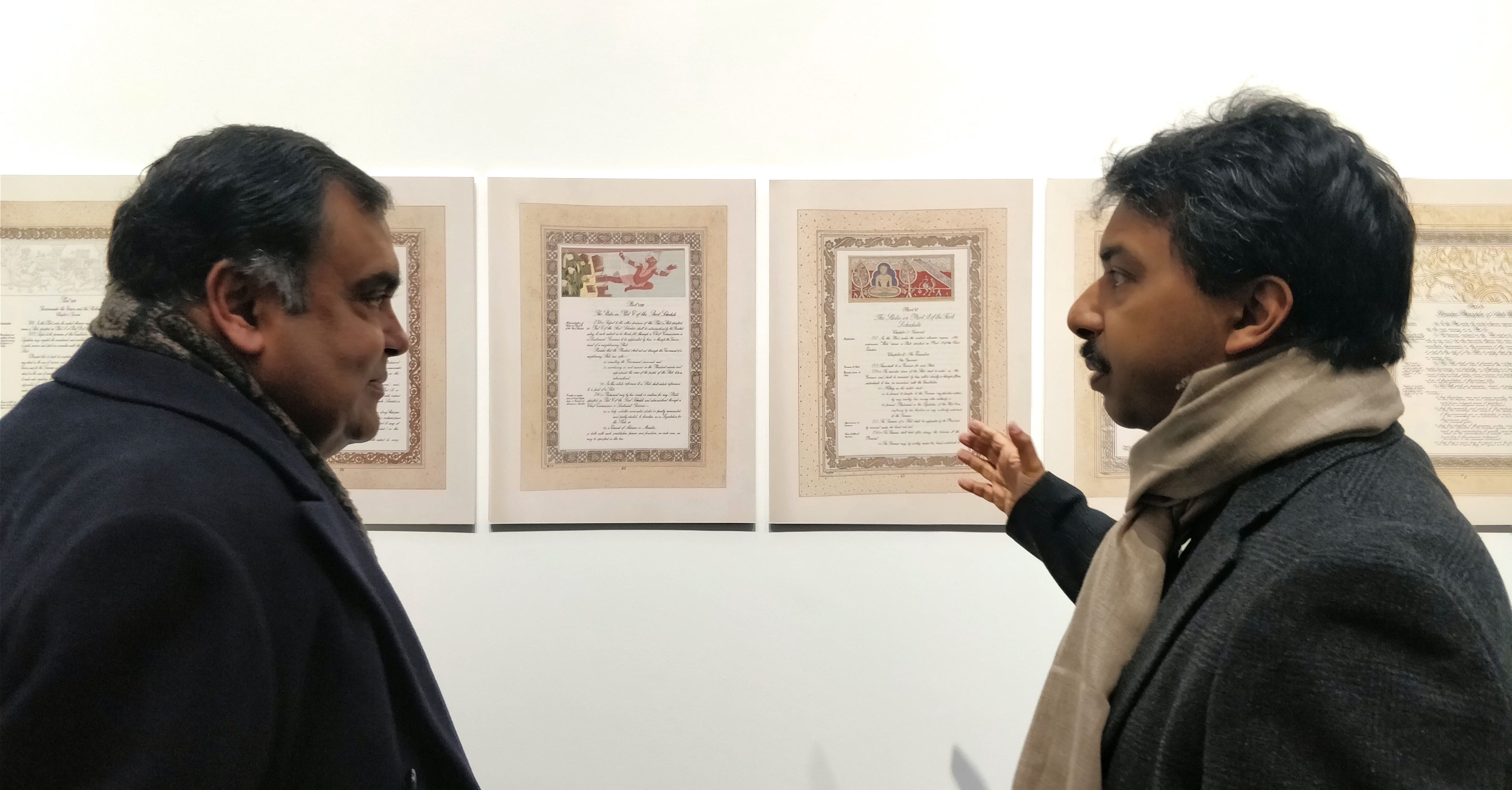

The Constitution of India

Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, born in the lowest rung of the brutal hierarchy of the Hindu caste system, fought his way to emerge as one of the greatest scholars of his generation. An alumnus of the London School of Economics, where he earned his Master’s degree in 1921 and his Doctorate in Economics in 1923, Dr Ambedkar was appointed the Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee two weeks after India gained its independence on August 15 1947. The Indian constitution, which was adopted on November 26 1949, is the longest written constitution in the world. For the last 70 years, it has been at the centre of attempts to define, defend, and defame the idea of modern India. Recent political and social developments, however, have led to some questions on whether the constitution needs to be updated to reflect the modern ideal for Indian-ness. The final theme of the LSE India Summit explores this fascinating document and asks the question, ‘do we need a new Constitution for India?’

For 70 years, independent India has endured, despite proclamations that predicted its imminent demise at the time of its tumultuous and painful birth. India @ 70: The LSE India Summit 2017 is both a celebration of the country’s independent history, and an examination of how developments from the past and present are shaping the future of the world’s largest democracy.

India @ 70: LSE India Summit, presented by Apollo Tyres Ltd, takes place at the Habitat Centre in Delhi on 29-31 March 2017. Click here for more information about the conference, including a full conference schedule. Tickets are currently sold out but a limited number of additional places will be released on 7 March and will be available here.

About the Author

Harish Alagappa is a writer signed with the Asia Literary Agency and is currently working on his first book. He was formerly an Assistant Editor with the New Delhi-based think tank, TERI (The Energy and Resources Institute), and has written for The Times of India, The Encyclopaedia of Energy, The Score Magazine, and Sportskeeda. In his spare time, he’s an amateur stand-up comic, quiz enthusiast, and Radiohead aficionado. He tweets @chaosverse.