At Pakistan @ 70: LSE Pakistan Summit 2017 Tahera Hasan spoke on the Philanthropy and Institution-Building panel in her capacity as Director of Imkaan Welfare Organisation. After the session Sonali Campion caught up with her to discuss Imkaan’s work and the problem of child abandonment in more detail.

At Pakistan @ 70: LSE Pakistan Summit 2017 Tahera Hasan spoke on the Philanthropy and Institution-Building panel in her capacity as Director of Imkaan Welfare Organisation. After the session Sonali Campion caught up with her to discuss Imkaan’s work and the problem of child abandonment in more detail.

Tell me about Imkaan Welfare Organisation – why was it established and what do you do?

Imkaan’s was established to deal with infanticide and the abandonment of children and to ensure that there is a support system and counselling system available for families pre- and post- placement. I’ve been working as a lawyer for the last 22 years and a lot of my legal work focus has been on adoption. I had personal experience of existing organisations which weren’t following certain protocols that make it easier for adopting parents and for children that are being placed to deal with the emotional aspects of the situation. We wanted to have international standards – the Hague Convention specifies a list of things that need to be looked at when you are placing a child for adoption, or when you are looking at a potential family.

There is no formal structure for adoption in place here, it is not recognised by the state. It is guardianship of the child that is given to adopting couples. Normally you will find that people who are going in for adopting children are those who’ve been suffering through infertility treatment and have not been able have children of their own.

When we started we conducted research in Machar Colony, which is one of the largest katchi abadis in Karachi with a population of 700,000. We guessed that because it’s the largest unregulated neighbourhood the number of abandonments there would be greater than anywhere else in the city. We conducted research there for about two years before we actually set up operations, and we discovered that it was a completely marginalised community, primarily Bengali/Burmese which meant there was a lack of identity and as a result the facilities that should normally be provided were not.

Our primary focus has been the child in any given situation, so when you ask me what we do the answer will be we work with child welfare, whether it is the solid waste management programme, the maternity home, clinic or recreational centre, it is all centred around the welfare and well-being of the child.

During the research we developed community linkages through interaction on a daily basis, and all the projects we have gone on to do were based the needs that were identified and what kind of reaction the community would potentially have to the kind of interventions we were proposing. For example, there were virtually no medical services. Most healthcare services were based on untrained medical practitioners. So we set up a mother and child healthcare clinic in 2014.

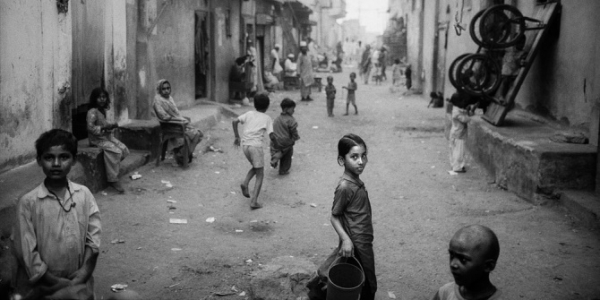

When you go into the locality you will find that the children are out on the streets. There are a few schools but an average family in Machar Colony has 8-10 children and no one can afford to send all of them. There’s a shortage of space inside because the families live in one room spaces. The moment children are out on the street there is increased vulnerability. There are anti-social activities, there’s abuse and so on. On the steps of our clinic we often found children age five or six gambling every day. That is something which struck a chord with us and we decided we needed to have something in place to get these children into a safe environment. So we set up Khel – which means ‘play’ in Urdu – as a recreational centre with no element of learning in it in terms of education. The objective was just to get these children off the street into a safe place to play. That’s it.

It was difficult at first because you had these children who were running wild basically, there were no checks and balances, they were coming from backgrounds where they had been through tough situations. The first month and a half we literally had children bouncing off the walls. We did not even think of doing anything structured, we just said ‘let them come in, let them get rid of their energy and we will take it from there’.

However, over a period of time there has been a change of behaviour. At the beginning we couldn’t take a crayon in without it being destroyed or stolen. Today the dynamic is very different; the change I see in the children is phenomenal. We have them taking ownership of their space, and protecting and caring for the children around them. We laid down ground rules from day one: ‘you need to keep yourself safe, you need to keep the people you’re with safe and you need to respect and care about the space that you’re in’. The children responded.

Today we have the sports programme. We have teenage girls playing table tennis even in a community as conservative as that one, they’ll go out for tournaments and so on, all with permission of their parents. We now have gymnastics teams both for girls and boys. The boys’ team was obviously easier to establish, gymnastics is a body contact sport when you are learning so there were reservations for the girls but with the passage of time and interaction with the community most of those hurdles have been overcome.

The pressure that we got from the community as far as the children were concerned was the fact that we did not have a learning education component. People wanted the children to know how to read and write. So even though we’re not equipped to be a school and that was not what we set out to be we have added an education component. It is informal with a focus on basic literacy skills, mathematics, general knowledge, we have an art component and will be adding music. There is also a lot of interaction in terms of children coming out and being taken into different environments to perform. We have had events where they have sung, and done plays, which are all things which seemed impossible a year and a half ago.

Taking a step back to touch on the wider context, what are the drivers of infanticide and child abandonment in Pakistan? What are the trends in this area?

Abandonment is something that has been happening for a long time and will continue happening. There is a misconception that the child that is being abandoned is always a girl. It used to be that chances of abandonment were much higher for girls, but out of the ten adoption cases that Imkaan has done in the past two years we haven’t had a single girl. While the percentage of girls may be generally higher, the fact is boys are also being abandoned.

I think one of the major reasons for abandonment is illegitimacy. It is not normally poverty because when you have ten children the eleventh is not going to make a significant difference. It has to be a social problem beyond just having lots of children that cannot be dealt with. In most situations my analysis indicates that that is the driving force.

As far as statistics are concerned we have no consolidated numbers on abandonment. Even if we started doing research on it the cases we will have will be those where children are found dead because these are the only reported cases. So many cases are slipping through the cracks.

That said, the number of abandonments is going up. I deal with international adoption as a lawyer so I work with other organisations in that context. So I have a good sense of the placements that are happening through those contacts and the indication is that the number is rising.

You talked about illegitimacy as a key driver. What agency do couples have in controlling how many children they have and the circumstances under which they have them? Abortion is illegal, and contraception…?

Abortion is illegal here, contraception is not – the issue there is around people’s religious beliefs. We’re working with communities and we have a programme that deals with birth control, but it’s a sensitive subject. A growing number of people are willing to use contraception; there is definitely awareness and a need but social, moral and religious pressures are put on a couple to not use it. The other problem is if you come in for family planning after your eighth child it won’t make much difference!

I think resistance to birth control is going to be overcome with the passage of time as awareness grows and as these things are talked about more (even if they are never going to be talked about openly).

The panel talked about philanthropic organisations filling in for the state. In an ideal world, what would the government be doing to support your activities and also provide the services on a wider scale?

Solutions don’t lie with philanthropic institutions and they never will. We are literally a drop in the ocean as far as the larger landscape is concerned. I can’t claim Imkaan is going to run 100 colleges, schools and clinics and that will change everything – it won’t. If we are equipped with expertise, we have to take that and plug it in where the need is.

The government needs to make the policies. Once the policymaking is there, then the focus has to be the implementation of that policy. One does realise that there are a lot of things on a policy level that do exist but then they don’t filter down into the reality of what is happening. There needs to be a happy marriage between the two.

Do you feel able to have impact on policy?

We’re still a very young organisation but we are open to it. We are making our contacts and linkages. If you want a larger impact that is the next step. There is an impact in philanthropy, you do touch x number of lives but is that institutionalised? It’s a difficult question because people are not willing to work with the government for a variety of reasons, which can be understandable but you have to think about what you want in the long term.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Tahera Hasan is an advocate and runs the legal consulting firm Tahera Hasan & Co, and is founding Director of Imkaan Welfare Organisation, a philanthropic organisation that deals with infanticide and the abandonment of children in Pakistan. She practices law at all subordinate and high courts of Pakistan, specialising in family law and international adoption cases. Hasan is a contributing writer to World Music and She magazine, and is a founder of the Karachi Adoption Group. She is also the member of Karachi Bar Association, the Sindh Bar Council and the Sindh High Court Bar Association.

Tahera Hasan is an advocate and runs the legal consulting firm Tahera Hasan & Co, and is founding Director of Imkaan Welfare Organisation, a philanthropic organisation that deals with infanticide and the abandonment of children in Pakistan. She practices law at all subordinate and high courts of Pakistan, specialising in family law and international adoption cases. Hasan is a contributing writer to World Music and She magazine, and is a founder of the Karachi Adoption Group. She is also the member of Karachi Bar Association, the Sindh Bar Council and the Sindh High Court Bar Association.

Sonali Campion is Communications and Events Officer at the South Asia Centre. She holds a BA (Hons) in History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Comparative Politics from LSE. She tweets @sonalijcampion.

Sonali Campion is Communications and Events Officer at the South Asia Centre. She holds a BA (Hons) in History from the University of Oxford and an MSc in Comparative Politics from LSE. She tweets @sonalijcampion.