The use of Randomised Control Trials to evaluate development policies has garnered significant attention in the last decade. In this article, Mridulya Narasimhan and Advitha Arun take a closer look at the strengths and pitfalls of RCTs, and the potential to integrate these with approaches such as rapid fire testing.

The use of Randomised Control Trials to evaluate development policies has garnered significant attention in the last decade. In this article, Mridulya Narasimhan and Advitha Arun take a closer look at the strengths and pitfalls of RCTs, and the potential to integrate these with approaches such as rapid fire testing.

In addition to clinical biologists (and probably their assistants), every development-research enthusiast nowadays is fairly familiar with the term ‘Randomised Control Trials’ or RCTs. Since their inception in the early 2000s, RCTs have influenced research in development economics, and consequently, the careers of many aspiring economists or ‘randomistas’. Fast forward 17 years and today we ask ourselves the question ‘are RCTs the only way to measure and evaluate impact?’ or ‘are RCTs subject to availability bias?’. Although still regarded as the ‘Gold Standard’ in impact evaluations, the sheen on RCTs is slowly fading away, due to the high costs associated with them. Though RCTs help in answering what works, the question of why it works is left open. Newer and improvised methodologies are catching up with the trend to fill in these gaps.

The Gold Standard’s monopoly

Field experiments done in the past have helped policymakers answer certain essential questions, for example relating to the effects of distributing deworming pills or distributing free textbooks in schools. However, a major source of concern is that RCTs, by virtue of their design, tend to have high temporal as well as monetary costs. On an average, it takes half a million dollars to conduct a social experiment in the field. To put things into perspective, at least US $965 million has been spent on RCT-based studies in the past 15 years. In terms of the life-cycle of an RCT-based evaluation the journey from esoteric economic journals to pragmatic policy implementation can take an average of 4.17 years, with some flagship projects extending up to 10 years. This often results in a policy lag where the economic, social and political factors might have changed, raising concerns about the internal validity of these studies which is of first-order priority.

In certain cases, even if the transformation process from theoretical evidence to policymaking has been fast-paced, there are newer bottlenecks in the implementation process which the study may not have originally addressed. For example, Han quotes a study conducted in 2012 in Kenya that showed the effectiveness of short-term contract teachers in increasing test scores. However, the reality on-the-ground showed that the scale up was successful in a specific context i.e. only when a non-profit partner implemented the programme, rather than the government.

Thus, research design as well as implementation of RCTs bear equal relevance in determining the causal attributions. Angus Deaton rightly summarised this by stating that RCTs typically answer the question of ‘what works’ rather than why it works. Understanding the mechanisms of change, which is of paramount importance in policymaking, requires supplementing RCTs with other refined methods that can shed light on the causal pathway.

The era of optimisation

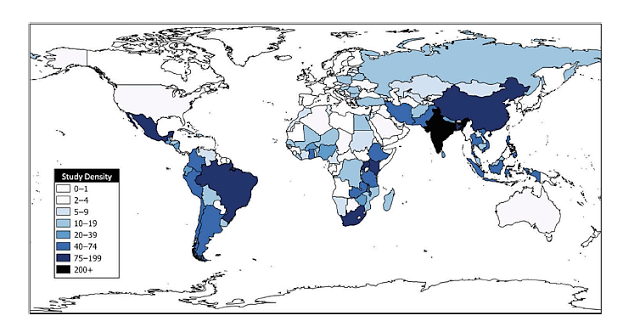

In the light of the perceived limitations of RCTs, the time is now ripe to seek innovations that make RCTs more efficient and effective. This is particularly important for a country such as India, which finds itself in a ‘missing middle’ situation with respect to international development aid. With 252 studies, India also ranks first in the number of impact evaluation studies conducted between 1981 and 2012. This points to an evident case of saturation with respect to development aid. The financial and time crunch in the current scenario indicates the need for optimised methods that can support governments and policymakers in taking evidence-based decisions, with no comprise on rigour.

Figure 1 Heat Map of low- and middle-income country Impact Evaluations (1981-2012)

Enter Rapid Fire Tests

Rapid prototype testing (A/B testing, or Rapid Fire Tests) refers to the process of evaluating program designs and improvising them, based on the impact they create. An evolved cousin of RCTs, A/B tests use behavioural insights to understand the reasons behind why a program may or may not work. For example, one might use different versions of SMS reminders to remind people about their savings commitments. Tracking such interventions over a period of time to understand the overall welfare impacts would qualify as RCTs, whereas rapid fire tests involve using secondary data sources to test whether specific targets have been achieved and incorporate changes to devise an intervention which is a better fit for the research and policy question at hand.

The use of A/B tests in driving social change has been pioneered by ideas42 and IPA in countries such as the Philippines, Peru, Uganda, Bolivia, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The focus thus far has been on issues such as increasing the adoption and use of financial services among the unbanked poor and better debt management among low-income populations.

In the developed world, the UK and US governments have acknowledged the potential of integrating behavioural insights with program delivery. As a result, a quasi-governmental entity – the Behavioural Insights Team – was set up by the UK Government, and the White House set up the SBST – Social and Behavioural Sciences Team.

In addition to this, one of the most credible validations to use the A/B testing methodology comes from IPA and Centre for Effective Global Action (CEGA). Their Goldilocks initiative highlights best practices that social entrepreneurs and non-profits can follow in monitoring and evaluation (M&E). The toolkit of methodologies includes A/B testing as an effective way of evaluation (IPA, 2016).

Two sides of the same coin

The main advantage that A/B tests offer over RCTs is that these tests are deeply intertwined with implementation, unlike traditional RCTs. By relying heavily on easily scalable interventions, A/B tests are pliant and help minimise the costs of evaluation and streamline scale-ups.

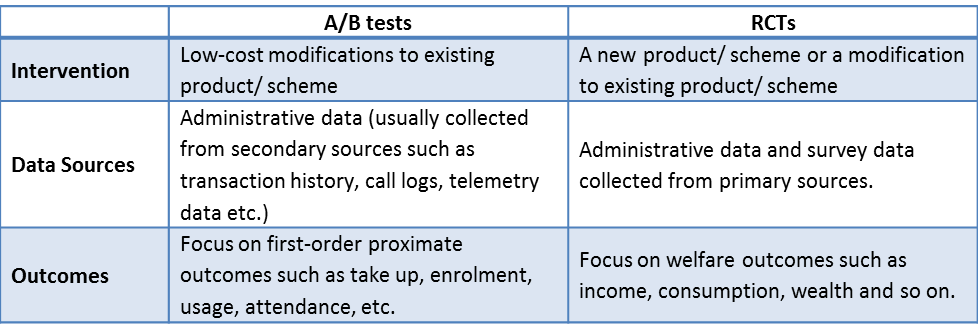

By focusing on administrative data collected, the feedback mechanisms under these tests are much quicker, and thus enable researchers to test several hypotheses within the given time and resource constraints. Further, primary data collected from administering household surveys runs the risk of using self-reported data in formulating policies. Using real-world data also has the advantage that the outcomes are relevant to the decision-making processes, which bear long-term policy implications due to high external validity (Pietri & Masoura, 2014). The following table provides a snapshot of the differences between RCTs and A/B tests.

Table 1 A Snapshot of Key Differences between RCTs and A/B Tests

In 2015, IDinsight proposed a separation between ‘Knowledge-Focused Evaluations’ (KFEs) and ‘Decision-Focused Evaluations’ (DFEs ). Whereas KFEs primarily aim to contribute to knowledge regarding development theory, DFEs are tailored methods that set sights on context-specific decision-making. In line with this, while RCTs are placed within the realm of KFEs, A/B tests which are intensive methods used for applied decision-making can be categorized as DFEs.

In India, IFMR LEAD has kicked off two studies using the methodology with capacity-building from ideas42, to test technology-based interventions. These studies include – a study focusing on increasing digital payment uptake and usage among small scale merchants; and another working towards improving private wealth management practices of Uber drivers. Such studies fall in the latter category of DFEs and hold the potential for being scaled up effectively.

To make RCT studies more effective, Sendhil Mullainathan, a proponent of cognitive economics suggests integrating ‘mechanism experiments’ into policy evaluations. Similarly, Maya Shankar, Senior Policy Advisor at SBST in the White House, stresses the importance of using behavioural understanding to define fundamental features of a policy or program to make it more effective.

The secret recipe for a successful evaluation

In the fight against poverty, researchers in the field of development economics have achieved a lot in the past decade. The emphasis on data and rigour for policymaking is praiseworthy. However, to inform development action more effectively, it is necessary to integrate several methodologies that can account for robust evidence in evaluation. Conducting either several short-term A/B tests or encompassing them into a large scale RCT can be a force multiplier. The choice of the methodology, however, should depend on the constraints as well as the potential to scale up the policy and sustain it in the long term.

Cover image: Monitoring and Evaluation in Uttar Pradesh, India. Credit: TESS India CC BY-SA 2.0

This article originally appeared on the Development Outlook blog and is reposted with the authors’ permission. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Authors

Mridulya Narasimhan is a Research Manager with the MSME and Entrepreneurship vertical at IFMR LEAD . She holds an Master’s degree in Public Management and Governance from the London School of Economics (LSE), and an Integrated Masters in Business Administration with a dual specialisation in Finance and International Business. She has been a Capstone Consultant with World Bank and previously worked in Corporate Strategy for Intertek Plc. Her interest in international development is grounded in the experience of living in India, Bhutan and China. She tweets @Mridulya.

Mridulya Narasimhan is a Research Manager with the MSME and Entrepreneurship vertical at IFMR LEAD . She holds an Master’s degree in Public Management and Governance from the London School of Economics (LSE), and an Integrated Masters in Business Administration with a dual specialisation in Finance and International Business. She has been a Capstone Consultant with World Bank and previously worked in Corporate Strategy for Intertek Plc. Her interest in international development is grounded in the experience of living in India, Bhutan and China. She tweets @Mridulya.

Advitha Arun is a Research Associate at IFMR LEAD. She is currently working on a project that involves understanding the digital finance scenario among merchants in India. Her research interests include development economics, gender economics and public policy. Prior to starting work at IFMR LEAD, she interned with Frost & Sullivan and Goldman Sachs. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stella Maris College, Chennai.

Advitha Arun is a Research Associate at IFMR LEAD. She is currently working on a project that involves understanding the digital finance scenario among merchants in India. Her research interests include development economics, gender economics and public policy. Prior to starting work at IFMR LEAD, she interned with Frost & Sullivan and Goldman Sachs. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stella Maris College, Chennai.