Pippa Virdee has been regularly crossing the land border between Lahore and Amritsar in the course of her research on partition and the history of Punjab for more than fifteen years. As Pakistan and India celebrate the 70th anniversary of independence, she reflects on how the border has evolved over the years.

Pippa Virdee has been regularly crossing the land border between Lahore and Amritsar in the course of her research on partition and the history of Punjab for more than fifteen years. As Pakistan and India celebrate the 70th anniversary of independence, she reflects on how the border has evolved over the years.

Located at a short distance of 24 kilometres from Lahore, Wagah is a small village in Pakistan placed strategically on the Grand Trunk Road; it serves as the main goods and railway station between India and Pakistan. The Indian counterpart is Attari and the two serve as the only official land border crossing between India and Pakistan.

The Wagah-Attari border is more accessible to foreigners than the citizens of India and Pakistan. Having used this route numerous times, it brings up all sorts of surprises every time. There is always a sense of uncertainty about the political climate between the two countries, which can change at short notice. When relations are good between them, the border seems a little more open and less hostile, there is generally more people traffic, especially those with green and blue passports. Otherwise, only the diplomats, foreigners and the select few cross the border. I am one of the privileged few. The Pakistanis always ask me if I’ve enjoyed my stay, and have I faced any problems? I always reassure them that I’ve had a wonderful time. The Indians it has to be said are less talkative, though on occasions I have been “treated” to cups of chai. With frequent visits, the staff now recognise me as the lone traveller between this no man’s land.

The Radcliffe Line that divides them was the scene of both immense horror and gratitude for those fleeing to the “promised lands.” Poignantly for writers such as Sadat Hasan Manto, many migrants were torn between the two spaces of no man’s land. This legacy continues today. Almost always there is plenty of dramatic material for the writers, artists, and peaceniks etc. that want to spend time here for inspiration. There is sadness as people (de)part, despair as people fail to cross over due to lack of proper paperwork, there are covert (or not so covert) spies keeping an eye on passengers, and then there are security/customs people who are keen to show their power and within the ordinary, there are the money changers and inquisitive coolies working hard, often in the full sun. But there are always people wondering about the “other”.

When I first crossed this border, over fifteen years ago, the border was a basic set-up in old “homely-style” colonial bungalows. You could literally walk across from one side to the other. Today, both have made this border into an airport-style, elaborate process with scanners and plenty of formalities and paperwork. Previously porters were employed to help carry people’s luggage to the international boundary that divides the two countries and they would also exchange goods that were permissible under trade agreements; the two carried on side by side. Now trade is exchanged more formally via the goods and transit terminal and the porters make their livelihoods through the meagre travellers passing through. Most of the labourers belong to Wagah and Attari and come from a generation of families who have lived and worked in this border area. It is unlike any other place in India or Pakistan. They have seen many changes and have many tales to share, and are often from divided migrant families themselves.

The Indian Border Security Force and the Pakistani Rangers have their daily ritual of lowering of the flag ceremony at the end of the day before sunset. Immaculately dressed, in Indian khaki and Pakistani black, the soldiers walk and strut in their fast paced and intimidating style. Michael Palin, during his travels around the world, compared this to the Ministry of Silly Walks from the Monty Python sketches; this is not too far-fetched. Often referred to as the strut of the peacocks, this is a show of prowess, power, and pride of the most superficial nature. Hundreds of Indians and Pakistanis flock to see this spectacle of jingoistic and patriotic display. Few would wonder about how this well-choreographed ceremony actually happens. It is in many ways an obscene drama that takes time to practice and perfect, and requires the two forces to work together. They do this away from the public gaze, so as to not taint the public image that both countries like to project. This tradition that started back in the 1950s has evolved now to only provoke the nationalist desire and to fuel this antagonistic relationship between the two countries. It has continued to grow, attracting foreign as well as local tourists.

Crossing the border only a few days before the 70th anniversary of the drawing of this line, there is more change. The Pakistanis are busy erecting a giant pole to hoist their flag in time for “celebrations” on 14 August. The official at the border remembers our previous conversation a few months back, he says, “madam ji, you were commenting on the Indians building their pole last time, come and see what we are doing. Inshallah it will be on full display by Monday.” I commented on the problems the Indians were having in sustaining and maintaining the hefty price/weight of their flag, which incidentally is empty at the moment. He retorts, “ours will be a superior quality!” I leave to cross over to India and wish them luck.

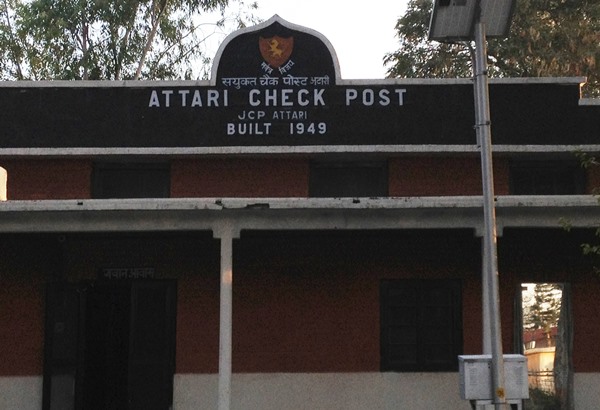

As I take the short walk to India, a similar construction site awaits me, like the Pakistanis they are busy expanding their seating capacity to accommodate the growing demand from visitors and tourists. As I walk on, I noticed one of the small remnants from the earlier days is gone, demolished to make way for the new buildings. The Attari Check Post from 1949 is no longer there. I had a brief chat with BSF solider and he was happy to confirm that it was gone to make way for new buildings. I shared the picture I had with him, he smiled and said “it is only preserved in pictures like this now.” It was the only building remaining from that period. Today the strong and stern buildings stand tall instead of the small informal bungalows that once operated here.

Seventy years on from when the Radcliffe Line was drawn it seems this border, if anything, has become even harder than previously. As I leave the border, there is sadness, there is always sadness. Very little divides the people of Lahore and Amritsar, yet so much division has been created between them in the interest of the nation states. The “two-nations” reign supreme.

This is an updated version of an article that originally appeared on the author’s personal blog Bagicha. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Dr Pippa Virdee is Senior Lecturer in Modern South Asian History at De Monfort University Leicester. Her areas of interest include British colonial history, the history of the Punjab, especially the Partition and its legacies, the construction of identity in colonial and post-colonial India and Pakistan, and the South Asia diaspora. Her work focuses particularly on the marginalised voices of Partition in an attempt to highlight the value and contribution of these silent voices.

Dr Pippa Virdee is Senior Lecturer in Modern South Asian History at De Monfort University Leicester. Her areas of interest include British colonial history, the history of the Punjab, especially the Partition and its legacies, the construction of identity in colonial and post-colonial India and Pakistan, and the South Asia diaspora. Her work focuses particularly on the marginalised voices of Partition in an attempt to highlight the value and contribution of these silent voices.