Preceding her lecture ‘The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Geographical Imagination of Pakistan‘ in October, Professor Lucy Chester spoke to Rebecca Bowers about her research on the enduring legacy of partition, and what can be learned from it today.

Preceding her lecture ‘The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Geographical Imagination of Pakistan‘ in October, Professor Lucy Chester spoke to Rebecca Bowers about her research on the enduring legacy of partition, and what can be learned from it today.

Your publication Borders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab has been described as the first full length study of this subject. Would you say there has been a dearth of scholarly material on this subject and if so why?

Yes. There is absolutely a real dearth of material on the boundary commission specifically with some really important exceptions. Joya Chatterjee has worked on the boundary commission of Bengal, and Willem van Schendel has also worked on the repercussions of boundary making in Bengal but I was really surprised at the lack of material on the Radcliffe commission itself maybe I’ll tell you how I got into this….

My sophomore year at University we were reading Wolpert’s new history of India which is a somewhat problematic textbook… but there was one paragraph on the Radcliffe commission and I just read that paragraph and I was like ‘this is bananas I need to find out more’ and I tried to find out more and discovered there was nothing written about it so as I got into it I realised that the main reason that is is that the source base is so limited because Radcliffe destroyed his papers and because a lot of the material… not so much on the British side but definitely on the Indian and Pakistani side is still so sensitive that it’s not accessible. And so that’s partly the reason I got so interested in maps. Because maps are one of the aspects of the Radcliffe boundary Commission source base that is more accessible and so I found that a really exciting way into analysing what actually happening.

I am hearing more and more the last couple of years younger scholars are starting to work on the boundary commission specifically, so my sense is that there is more happening and I want to give a shout out for a young scholar named Hannah Fitzpatrick who is at St Andrews who is a geographer who is working on the role or lack thereof geography in the boundary commission, so a lot of exciting stuff is happening in the last few years…

It’s interesting… when I thought about the image I put up on Twitter for this event (which was a map that was meant to be drawn along religious divisions) people asked ‘where did you get this map from?’ or complained ‘it doesn’t show this’ and so I can see how it’s controversial…

Oh yes. It’s so controversial and there are laws in both India and Pakistan about what maps can be distributed and published and there’s very strict censorship so yes maps are still mostly tied to national identities and national anxieties.

With this in mind as well how would you say that your work is now relevant in a wider context to Kashmir but also on a global scale as well?

I think the larger issue of partition is unfortunately still extremely relevant. There was for a while a lot of discussion whether or not the US should partition Iraq and there’s been less of that lately. But just a few years ago Sudan was divided in two and that resulted directly from partition era policies during the time of colonial control, so I think unfortunately partition and this whole idea that ethnic and religious conflict can potentially be resolved by geographical divisions is something that keeps coming up so I think unfortunately it’s very relevant. What I hope my work does is show that partition seems like a very attractive, very simple option, but it’s actually incredibly complicated and incredibly problematic and very, very difficult to do right.

You are currently exploring connections between British India and the Palestine Mandate. Can you talk a little about that and what research you’re up to now?

Yes so as I was finishing my book on 1947 in India, in the back of my mind I was thinking ‘I wonder what the British were thinking about India as they looked at Palestine which they withdrew from in 48’ and I went into it rather naively with the idea that I could find some lessons which British imperial policy makers were deriving from India and applying in Palestine and basically the short answer is there wasn’t any of that. There’s some really fascinating material… there’s a cabinet meeting in September 1947 where Prime Minister Atlee says ‘look at what’s happening in India right now’ September 1947 right in the thick of the violence in North India. There’s a close parallel to what’s happening in Palestine and basically he says ‘India can be a useful model to what’s happening in Palestine’. If he’s deriving lessons, they are completely the wrong lessons. I think the lesson he was trying to draw was ‘we need to just set a clear deadline and pull out after that deadline’. I think that’s a problematic lesson. So the much more interesting side of this is at the time is that there are all of these nationalist and anti-colonial actors both in India and in Palestine who are looking very closely at each other and or deriving lessons in terms of how to fight British power and British control. So that’s been a much more exciting side of it.

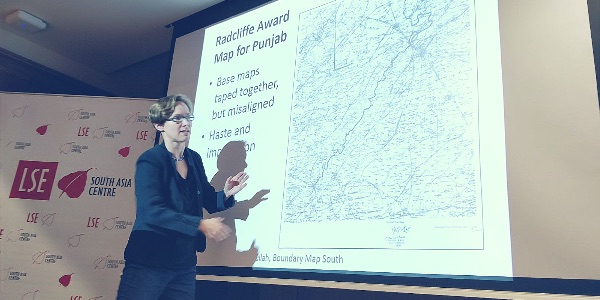

Professor Lucy Chester giving her lecture ‘The Radcliffe Boundary and the Geographical Imagination of Pakistan’ at LSE. Photo credit: Mahima A. Jain.

For our readers who are not attending tonight’s lecture but want to know more on this subject, do you mind giving a brief summary on what you are going to talk about

Sure. So this draws from my book on the Radciffe Boundary Commission and then from what I think will be my next project which is the pre 1947 geographical imagination of Pakistan. So the extent to which the whole Pakistan campaign and debate threw in geography and cartography and I’m going to try and weave that together and look at what was in many ways a lack of maps of where Pakistan would be pre 1947 and how that relates to the kind of maps that were used in the Radcliffe boundary commission process and then try to draw some larger lessons on what that means for partition more broadly. Not just this big piece where the line was drawn but the whole process which is very hasty, very poorly planned… very politically driven but disguised in this pseudo-judicial framework.

And would you say that in your career it’s been quite a difficult subject to study? What are the biggest challenges that you have faced as a scholar studying this area?

I have definitely got criticisms on my work on South Asia and focusing too much on the British for example and not allowing enough for nationalist agency and those are criticisms that I think are helping me in the direction of my next project looking at more nationalist imaginations and how they intersect with colonial imaginings of colonised territory. I have to tell you that navigating various controversies in South Asian history seems relatively easy compared to the controversies of going into Israel Palestine history!

You’ve chosen some very contentious areas…

I’m very excited about this India-Palestine connections project, but I am not trained as a Middle East historian so I’ve been accidentally stumbling onto these landmines – so I’ll be pretty happy to get back to South Asia!

Did you ever find it was difficult accessing any information or archives?

Anyone who has worked in South Asian archives will know that they are very difficult to work in. You just have to be very patient. You can’t count on anything in particular showing up. You have to go in with the attitude that if you get good stuff that’s great – that’s exciting. I’ve also had problems with being able to see that exciting material was there – for example, in the index… but it wasn’t accessible to me or it was classified sensitive.

It would be great to see more interdisciplinary research in this area. Geography, anthropology, history….

I hadn’t really thought about it in those terms before but I think in many ways because the source base is so limited you really have to be interdisciplinary and come at it from different angles to be effective.

Were you able to have many interviews with people who remembered partition? What were your experiences like with those people?

Oh gosh. Those are some research moments that I am most grateful for. People were just incredibly generous to me with their time and there were a number of cases where I had met people through family members and I would do an interview and the family member would say afterwards ‘my grandfather has never told us this’. I think there’s a really interesting dynamic there. I think somehow it can be easier to talk about horrendous things to an outsider rather than to someone you’re going to see every day.

Another thing that really struck me with the oral history stuff I did… this was 1999-2000 mainly 50 years after these events and almost all of the people I talked to, had a narrative already in mind. And I found that the interviews were best if I give them space to tell that narrative and then ask more specific questions that I wanted to ask because they had to get that out before they were almost physically capable of talking about more detail.

Cover image: Map showing ‘Prevailing Religions of the British Empire 1909’. Image credit: John George Bartholomew, Public domain.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

Professor Lucy Chester was awarded her PhD in History from Yale and currently teaches at the University of Colorado, where she is Associate Professor of History and International Affairs. Her recent research compares Britain’s withdrawal from India and the Palestine Mandate. She is the author of ‘Orders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab’.

Professor Lucy Chester was awarded her PhD in History from Yale and currently teaches at the University of Colorado, where she is Associate Professor of History and International Affairs. Her recent research compares Britain’s withdrawal from India and the Palestine Mandate. She is the author of ‘Orders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab’.

Rebecca Bowers is a blog editor at the South Asia Centre and a final year PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the London School of Economics. Rebecca’s research explores the lives of female construction workers and their families in Bengaluru, India.

Rebecca Bowers is a blog editor at the South Asia Centre and a final year PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the London School of Economics. Rebecca’s research explores the lives of female construction workers and their families in Bengaluru, India.