India’s unorganised labour industry makes up around ninety-three percent of the country’s total workforce. Much of this work is done behind closed doors and by women. On the streets of Delhi, Sumedha Pal discovers the conditions many women have to endure. Here she argues why India has a chance to transform these women’s lives with the country’s draft Social Security and Welfare Code.

Down a narrow alleyway inside a dimly lit basement of Sonia Vihar, a suburb of India’s capital city, twenty-eight year old Soni works with her children stapling together banners that read Happy Birthday. “I get paid 40 rupees to assemble 100 pieces,” she tells me. “I spend almost all day making them.” Along another lane, forty-year old Neelam is hard at work on eight kilos of plastic flowers – her allotted amount for the day, for which she is paid a meagre three rupees per kilo. “I am the only one who does this in my family,” she says to me. “Alongside this I have to take care of the household as well – whatever money I make from this, I use it for my family and home.”

India’s garment industry is among the world’s biggest for manufacturing, employing 12.9 million people in formal factory settings, however millions more are indirectly employed and therefore unaccounted for in informal, home-based settings. In fact, India’s informal workers amount to around 93 per cent of its total workforce. On 8th January of this year however these workers went on strike to demand an improved wage and social security. Left invisible in the country’s labour narrative, this collective action exposed how many of India’s workers are home-based, and largely women.

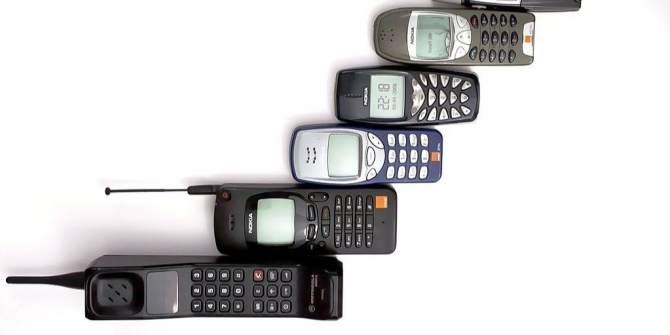

Photo: Soni making “Happy Birthday Banners” Credit: Sumedha Pal

Photo: Soni making “Happy Birthday Banners” Credit: Sumedha Pal

The scale of invisible labour

The International Labour Organisation’s definition of home-based workers includes all workers who carry out remunerative work within their homes or in an adjacent location or in any location that is not the workplace of the employer. Home-based workers can be further categorised as (i) self-employed workers (ii) homeworkers and (iii) employees differentiated through type of contract, nature of remuneration. In the Delhi, thousands of men and women work for contractors or large international clothing labels from their homes, often assembling small parts in poor working conditions. Despite the work they do, these workers are often rendered invisible in the realm of law and policy.

In a comprehensive attempt at understanding the work of these women, research by the University of California, Berkeley found that women and girls from the most marginalised communities toiled for as little as 15 cents (11p or Rs.10-25) an hour in homes across India.

Indeed, this year’s Indian Exclusion Report highlighted the adverse impacts on the health of the workers – more specifically, garment workers and weavers were more likely to experience abdominal pain and miscarriages due to continuous pedalling. Postures and poor lighting conditions result in eye problems and joint pains among garment workers and pottery workers. Also constant inhaling of agarbatti (incense) fumes causes persistent cough, cold and bronchial problems. Similarly, in the handmade paper sector, workers face immense health risks due to the chemicals they are exposed to during their work.

The gendered nature of invisible work

The nature of work is also intrinsically connected to the patriarchal notion of women needing to be guarded and kept inside homes. Since most female home-based workers earn their living in their home, what work they do, and the effort and the time spent goes unnoticed. A home-based worker in Delhi’s Sonia Vihar, Usha Amma told me, “If we work outside, it is deemed unfavourable for us, this is why we stay at home.”

The work that these women do in their houses is therefore left invisible in the eyes of the community, but also in the law and policy makers as these women are not even recognised as workers. Additionally home-based workers remain at serious disadvantage even in comparison to most other workers that fall under the category of unorganised sector. As the workers lack the ability to hold any bargaining power with the contractors, they are often isolated within the home, with limited opportunities to interact with other home-based

The draft social security and welfare code

Currently, India is gearing up to bring changes to its social security code. The code is aimed at the universalisation of social security benefits to all workers based on a rights-based approach, including both in the organised and the unorganised sector. This brings us to the ignored informal sector (including home-based workers,) and the Labour Code on Social Security. The Social Security Code will require all workers to be registered by their employers. In the case of home-based workers however it is often difficult to identify the employer, as multiple contractors are usually involved.

By the code putting the onus of registration on the employer, who may not always be willing or interested to do so, the inclusion for these women in the social security benefit system will be left down to the good will contractors. Furthermore, the under the current proposals, workers will not be able to confirm that they are working in a form of sub-contracted, self-employment, as a worker will only be able to confirm if they are one of the either. The code therefore misses some crucial nuances catering to home based workers.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting. Photo credit: Flickr, Ishan Khosla

Sumedha Pal is a Journalist at Newsclick.in. She writes about politics, social movements and gender.