Amid protests, it is the quotidian lessons of citizenship that have been taught and practised over seven decades that are now being used to express what it is to be Indian, argues Mukulika Banerjee (Director, LSE South Asia Centre).

In a small village in West Bengal, every year on 26th January, a young schoolteacher called Akhtar organised a picnic for the children of the village.

On India’s Republic Day, with schools closed and no family-oriented activities, as there are on religious festivals, the children missed nothing by being away from the village. Akhtar knew most of the children personally, either as students at his school or as their private tutor. The quality of his tuitions was considered very good given that he possessed a rare degree in English, and so any knowledge that he could impart was at a premium. His widowed mother fiercely believed in the value of education for her two sons and one daughter, and made sure they all went to university, inculcating in them the importance of supporting education wherever they went.

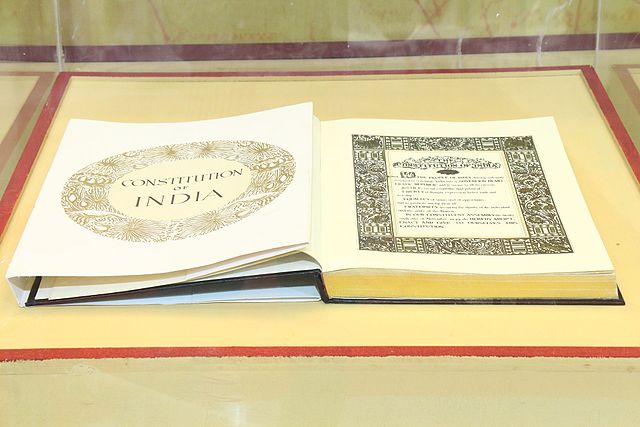

On 26th January, Akhtar rounded up the children and, as the national flag was unfurled, they sang the national anthem and sweets were distributed to everyone who stopped by. Then he took the children for a picnic, which they called a ‘feastie’, to a little copse about a couple of miles away, not far from the edge of the highway. It was a lovely spot, with some unusually large trees, the ruins of an old inspection bungalow and a dried-up river bed. Akhtar read out the Preamble of the Indian Constitution, after which he explained to the children that these were the very words that were read out on the same date in 1950 when India became a Republic, and gave a brief commentary explaining the meaning of the words in it. The children then played some games he organised and won small prizes of stationery and books, after which everyone enjoyed a modest picnic of muri, salted peanuts and fruits. By late afternoon, the children were back in the village.

While Akhtar did not intend to make too obvious a statement by this gesture, the choice of Republic Day to mark his ritual calendar was of course heavy with symbolism. He was the most educated member of the village but kept his distance from all party politics, including all Left politics, which was dominated by the local comrade. Nor did he overtly support the opposition party his brother had initiated. He also tended to stay away from Eid and other religious festivals and weddings as he found them wasteful and claustrophobic. Instead, he chose to invest his personal money and time on Republic Day, preferring a ‘modern’ and ‘secular’ ritual as his contribution to the social life of the village.

In the short speech that he made to the children, Akhtar drew their attention to the Preamble’s words and explained the significance of living in a Republic, what being a sovereign citizen meant, and the rights and responsibilities it brought to each of them. Quietly, he underscored that while they were too little to vote, they should not forget that India’s founders had laid the foundation for political and social equality through universal franchise and urged the children to always remember that.

Akhtar himself belonged to the elite Syed caste and had benefited from having had an education up to the Masters level. This little celebration allowed him to also mark his commitment to a wider distribution of this privilege, which he practised the rest of the year through free and excellent tuitions for those who could not afford to pay. By including children from every household, regardless of caste and religion, and by taking them away from the glare of the village, Akhtar was able to avoid any debate and competition with anyone else. In a context where very few social activities were arranged purely for children, people in the village saw his gesture as noble, affectionate and progressive, if slightly eccentric.

I never got to know Akhtar very well, or ‘Akhtar Master’ as we all called him, despite having visited his village for over 20 years. But his picnic stood out for me as a unique moment in the social life of a community when an otherwise taciturn adult went out of his way to do something meaningful for the children of the village and made it fun. At this point in India’s history, when millions feel the very constitutional soul of the Indian Republic is under assault, it is possible to see the real worth of Akhtar Master’s gesture and that of all the Akhtar Masters across India. They have celebrated and taught future generations the values of the Republic and an Indian citizenship — sovereignty of people, the secular basis of our political foundations, the importance of civic participation, civility in competition, the importance of team spirit and the joys of togetherness. As one watches India erupt in a wave of popular protests and demonstrations unfettered by the petty rivalries of political parties, of the young providing leadership to the disillusioned, of 90-year-old women inspiring young men to keep up, it is the quotidian lessons of citizenship that have been taught and practised over seven decades that are now being used to express what it is to be Indian.

On this Republic Day, I hope that Akhtar is holding his feastie as usual, and I expect there will be a few extra goodies for the children on this special 70th anniversary.

This article was first published on 26 January, 2020 at The Indian Express.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Image Credit: Constitution of India at the Geospatial World Forum 2017, Hyderabad, India (Geospatial World CC BY 2.0).