In a significant step towards digitalisation, India’s payment and settlement system has recently witnessed a transition from manual to automatic. Initiated in the 1990s, the digital payment and settlement system has undergone a massive transformation, therefore serving as useful model for other developing economies, argues Nufazil Ahangar (Central University of Kashmir, India) and Farooq Shah (Central University of Kashmir, India).

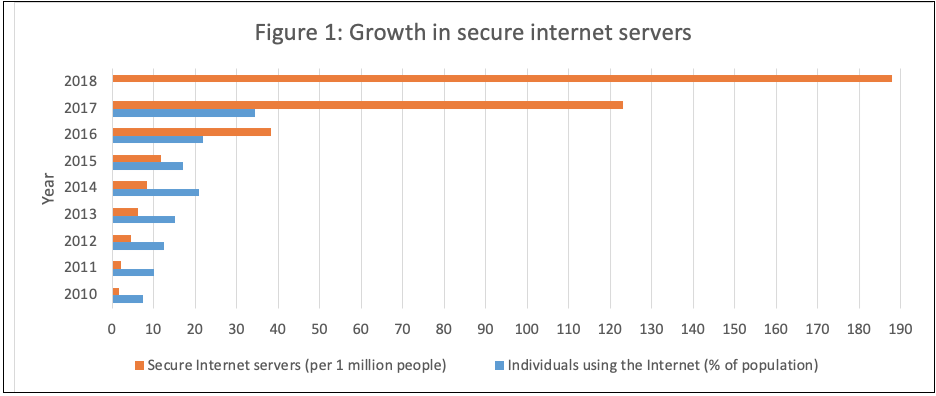

Over the past decade, India has witnessed a progressive trend in the number of secure internet providers and individuals using the internet. The World Bank Netcraft Secure Server Survey estimate reveals that secure internet servers per 1 million people increased from 1.66 in 2010 to 187.80 in 2018. In addition, the World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and Database (World Bank) shows that individuals using the internet as a percentage of population grew from 7.5 in 2010 to 34.45 per cent in 2017.

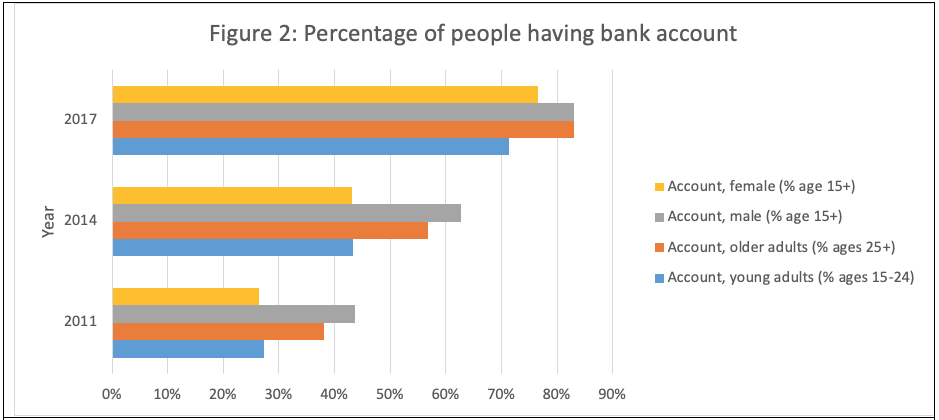

Furthermore, over the last decade, India recorded a sharp rise in financial inclusion. The World Bank’s Global Findex Database used as its measure the “spread of bank accounts” for financial inclusion, and according to their estimates, the percentage of young adults (aged 15-24) who have an account (by themselves or together with someone else) at a bank or financial institution increased from 27 per cent in 2011 to 71 per cent in 2017. However, for older adults (aged 25+), the figures increased from 38 in 2011 to 83 per cent in 2017. This sharp rise in the number of bank accounts is also observed across genders: the percentage of bank accounts held among men (aged 15+) increased from 44 per cent in 2011 to 83 per cent in 2017, while as for women in the same age group, the number increased from 26 per cent in 2011 to 77 per cent in 2017.

Source: World Bank Netcraft Secure Server Survey and World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and Database;

Source: World Bank’s Global Findex Database

With the massive growth in internet connectivity on the one hand, and the sharp increase in the number of bank accounts on the other, the challenge India faced was to enhance the electronic payments and settlement systems across the country – systems that would reduce transaction costs, be safe, secure and efficient, reduce the branch visits and most importantly, be trusted by users.

The steps taken to achieve this have included the introduction of debit and credit card based payments and electronic clearance services (ECS) in the 1990s, followed by the electronic fund transfer system in the 2000s, and real time gross settlement (RTGS) and national electronic fund transfer (NEFT) in 2005. The amplified penetration of banking, coupled with enhancement of internet and banking operations, brought in challenges of regulation and supervision.

Accordingly, the Payment and Settlement Act (2007) came into being that authorized the Reserve Bank of India to build a robust digital financial infrastructure, draft an effective supervisory and regulatory mechanism, and introduce a customer centric payment and settlement system. Since the development of a strong digital financial infrastructure is a comprehensive process, it has comprised three major phases:

Phase 1: The introduction of the unique identification codes

Phase 1 involved the introduction of the unique identification codes in order to verify the identity of each resident. In January 2009, India adopted “Aadhaar biometric identity system”. Aadhaar requires biometrics (fingerprint and iris scan) and photograph (headshot) for identification. In addition, it carries information on four demographic points: name, date of birth, gender and residential status to generate a 12-digit unique identity number (Aadhaar) that is stored in the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) silos.

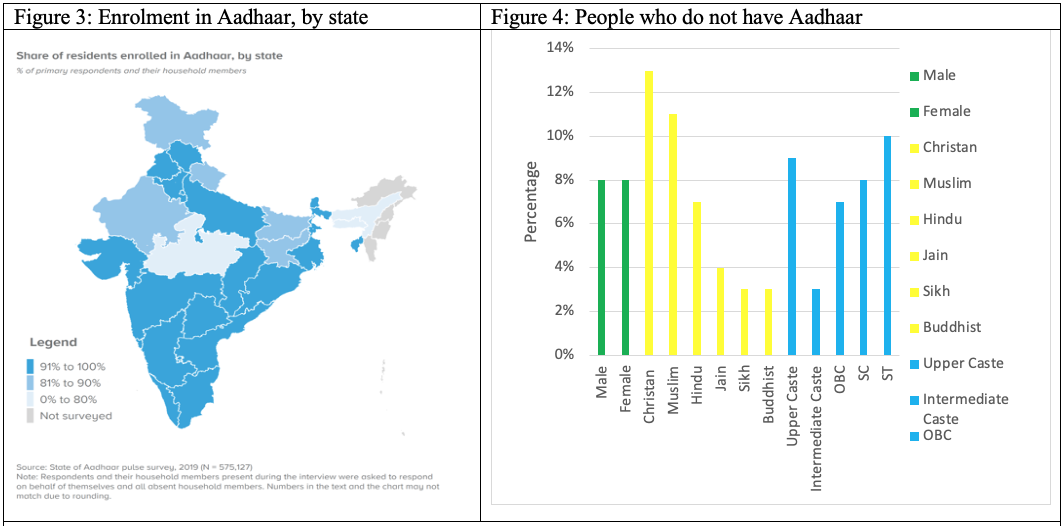

Currently, Aadhaar is the most widely used ID with high enrolment levels across the country. Figure 3 presents the share of residents enrolled in Aadhaar by state. The figure reveals that more than 90 per cent of residents in India (an estimated 1.2 billion people) have Aadhaar. In fact, enrolment for Aadhaar is currently more than the voter ID in India with 15 out of 28 states and union territories having enrolment level of more than 90 per cent. Despite this huge Aadhaar enrolment, a sizable minority still does not have yet Aadhaar, which mostly include marginalised groups. According to the State of Aadhaar Report 2019, some minority religious groups like Christians (13 per cent) and Muslims (12 per cent) have higher non-enrolment levels than the national average of 8 per cent. In addition, among marginalised groups, scheduled tribes (ST) have lower levels of enrolment than other backward classes (OBC) and intermediate castes. However, there was no enrolment difference between men and women according to the State of Aadhaar Report 2019.

Sources: Figure 3 and 4 State of Aadhaar Report 2019

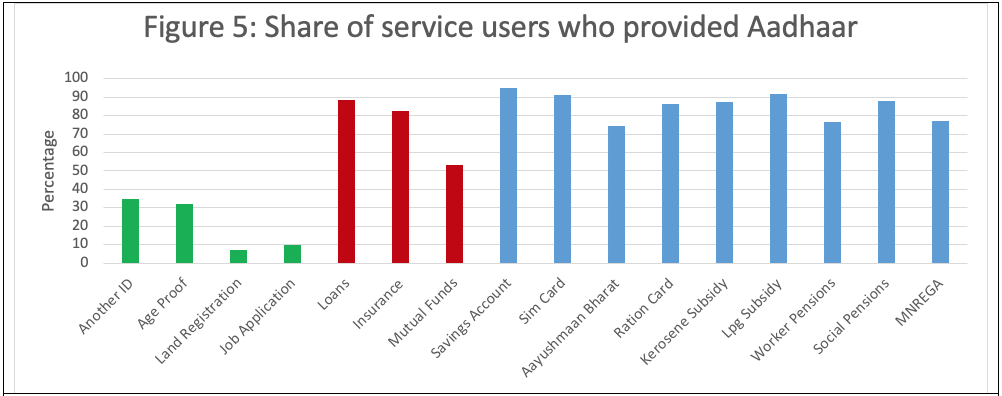

Furthermore, Aadhaar is now used as a general purpose form of identity and is usable across various consumer conveniences and services. In fact, the statistics of State of Aadhaar Report 2019 reveals that Aadhaar is used even when it is not mandatory. Figure 5 shows the share of service users who have provided Aadhaar either voluntarily or mandatorily. In this figure, both green as well as red lines represent Aadhaar as not mandatory but voluntarily used; green lines represent voluntary use of Aadhaar for non-financial services and red lines represent voluntary use for financial services. In addition, blue lines in the figure represent Aadhaar ‘can be mandatory requirement’. ‘Can be mandatory requirement’ is defined as per the 2018, Supreme

Court of India ruling on Aadhaar: “Aadhaar can be made mandatory for targeted government welfare benefts and can no longer be made mandatory for private-sector service delivery”. However, the data in the figure suggest that Aadhaar is used in almost all mandatory requirements besides being used voluntarily for availing financial services.

Another important application of Aadhaar is its use for e-KYC (know your customer) process. Besides being paperless, Aadhaar based e-KYC is a cheap, fast, hassle-free process. Moreover, it reduces the risk of document forgery as service providers can use customer biometrics, demographic information and photograph for verification in a fraction of second.

Source: State of Aadhaar Report 2019

Phase 2: Digital financial transformation

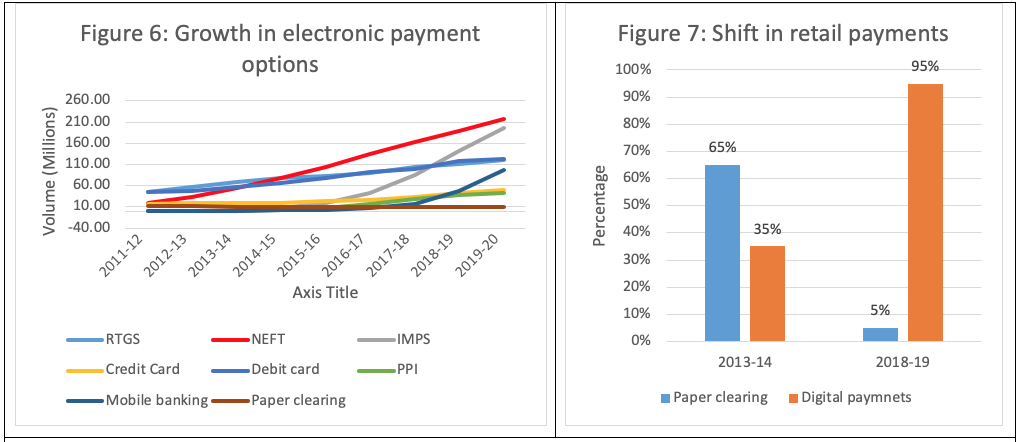

Phase 2 focussed on the digital financial transformation by enhancing the real time payment and settlement system. Towards this end, India implemented a series of electronic payment (EP) options offering customer to customer (C2C), business to customer (B2C) and business to business (B2B) interface. These include real time gross settlement (RTGS), national electronic fund transfer (NEFT), immediate payment system (IMPS), credit cards, debit cards, mobile banking and prepaid payment instruments, comprising mobile wallets and prepaid cards.

Figure 6 below shows the growth in EPs from 2011-12 to 2019-20. All the EP options show a sharp growth with NEFT, RTGS, IMPS and mobile banking being significant contributors to the growth, while as credit and debit cards registered comparatively a lower growth. The popularity of EPs has led to a sharp fall in paper clearing across the years. Interestingly, retail payments shifted to a digital mode from 5 per cent in 2013-14 to 65 per cent in 2018-19. In a same manner with 35 per cent in 2013-14, digital clearing rose to 95 per cent in 2018-19 (see figure 7).

Sources: Figure 6 – Reserve Bank of India; Figure 7 – BIS paper 106

Phase 3: Data Sharing

Given the increasing link between internet and banking, increasingly large chunks of data are generated. Therefore, the last phase in the development of digital financial infrastructure was to develop the effective mechanism of data sharing. For this, India, through the RBI, adopted regulated data fiduciary entities called account aggregators. Under this system, the data is shared within the regulated financial system with the customer’s knowledge and consent. With data sharing, customers can also reap the benefits of the

data they generate. Earlier, newly created data was retained in proprietary silos of a particular organization and was not shared. However, with data sharing, customers can show evidence of income and businesses to attest revenues and earning potential, thus improving access to credit and other financial services.

To conclude, India’s digital financial infrastructure development is definitely a well-built model that can be replicated by states across the world that are desperate to digitally revolutionize their payment system. However, this model may not fit in to all jurisdictions keeping in view the peculiarities prevalent across the countries. However, India’s digital transformation journey can serve as a reference to deal with the technicalities and nuances.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Photo: Online Payment Card. Credit: Rupixen, Pixabay.

Nice and informative writeup.