Earlier this year, the Indian government presented figures to the parliament on the number of suicides caused by financial distress in the country. Bankruptcy was shown as an important cause of such deaths. Raman Singh Chhina argues below that, while no panaceas are available, the government can provide more effective help to people who are unable to pay back debts due to negative life events by implementing and systematically improving the proposed consumer bankruptcy code instead of resorting to ad hoc and politically-motivated debt-waivers and other such debt-relief packages.

Insolvency in the Indian formal and informal credit economy remains ridden with violence. In 2017, a lower caste couple in Uttar Pradesh was brutally murdered by their local grocer for a debt of 22 cents [17 pence]. In the same year, six members of a family who ran a school in Madurai were found dead inside their house. They left a note which blamed their debt as the reason for suicides and pleaded the authorities to settle their debt posthumously — by selling their home and other property. Farmer suicides due to insolvency over the last two decades have been a source of seething anger in the north Indian states and manifested in the year-long protests against the farm bills in 2021. More than five hundred lives were lost in the protests and at least five of them were by suicide.

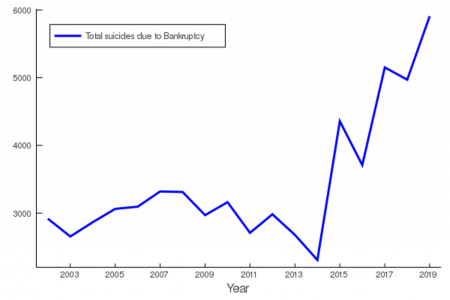

The data on suicides confirms the prevalence of deaths of despair among insolvent debtors. The number of suicides caused by Bankruptcy remains significant, and has been on a consistent rise since 2015. The ‘Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India’ data collected by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), plotted in Fig. 1 for the last twenty years, shows at least a few thousand suicides every year attributed to Bankruptcy. Given the inefficiencies that remain in the data collection in India, there are strong grounds to suspect that the numbers are severely under-reported. The actual number could be anywhere between twice to even five times the numbers shown in the figure. It is also not clear why the number has been rising since 2015. The actual reasons could be anything ranging from the financial distress caused by demonetisation in 2016 to the harsh measures for debt recovery used by the new array of micro-finance loans, or the already existing farm crisis.

Fig. 1. Source: Data from National Crime Records Bureau, Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India.

The Government Response

The government has responded unreliably to this crisis. Most of the mature economies have extensive Bankruptcy provisions for the consumers when they are not able to pay back their loans. In 2019, in US, for example, 733,000 bankruptcy petitions were filed by individuals with debts that were predominantly consumer in nature. Consumers filing these bankruptcies represented $83 billion in assets and total liabilities of $113 billion. On top of a social safety net these policies help people who are no longer able to pay back their debt due to unforeseen life events such as unemployment, illness, death of a family member etc.

The Indian government’s policy on the other hand has been completely incoherent, and has tried to deal with this issue by a populist approach of mass debt-waivers and bailouts.

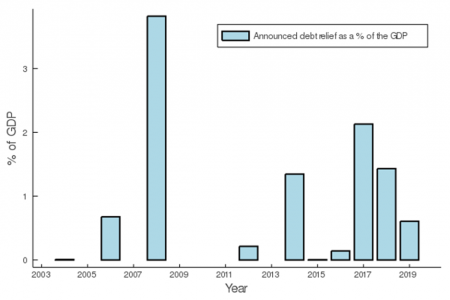

These debt-waivers almost exclusively target farm debt and have completely left the crisis looming large for people employed in other sectors. In the last three decades, the central government has issued massive debt-relief packages twice – in 1990 and 2008 respectively. In addition, there have been scores of waivers announced by various state governments over the same horizon. Fig. 2 shows the total announced debt relief packages as a fraction of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in that year. The inconsistency is apparent with as much as 3% of the GDP announced in some years but no help announced at all in others.

Fig. 2. Source: Data compiled by the Author.

Note: that these are the announced amounts. Actual implementation varied in all the schemes.

Much of the concern about these mass debt-relief packages has been a criticism of their deteriorating the rural credit culture or elevating the moral hazard problem: that if people know that a debt waiver would be announced soon, they would not honour their repayments. An influential study by Martin Kanz at The World Bank’s Development Economics Research Group, using data from four rural districts in Gujrat post the 2008 agricultural debt bailout, found that debt relief had led to greater reliance on informal credit, reduced investment and lowered agricultural productivity. They also found that it increased the moral hazard issue by lowering the beneficiaries’ concern about the future default. Further, we don’t even know how well the relief gets targeted in these policies, i.e., is it received by people who are actually at the edge of bankruptcy or whether it is appropriated by people who are going through temporary shocks to their incomes and abilities to pay back the loans. These policies leave a vast majority of distressed consumers just waiting in vain.

The Urgent Need for a Debate

A useful policy instrument which helps insolvent consumers face these extreme economic hardships in most developed countries is the bankruptcy law. In the US, for example, a consumer can file bankruptcy under Chapter 7 and the Chapter 13 of the US Bankruptcy code. In Chapter 7 the defaulter ends up getting all their assets liquidated and left with only the remaining proceeds after paying the creditors. But they are relieved of all the debt and can start afresh soon. Under Chapter 13, the consumer is allowed to keep their assets but they are put on a strict repayment plan. In India, for a long while there was no such provision. In 2016, the Modi government introduced the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code which some have touted as the government’s most important reform in all its years in power. Chapters 2 and 4, in Part III of the code, detail the process to be followed by individuals who want to get a fresh start or declare bankruptcy for their household debt. The laws, however, have not yet been implemented.

An institutional structure without the option to declare bankruptcy reinforces the wrong assumption that credit is indulgence; and ergo the wrong conclusion that the coercive recovery practises are a just punishment for overindulgence. It ignores issues such as predatory lending, economy-wide job losses or lack of fair prices to producers for their produce that shrink their income. There definitely could be other reasons or vested interests in not paying back but even leading research from two University of Chicago faculty shows that more than 70% of the mortgage defaults in a country like the US are triggered by negative life events such as illness or job loss and not by strategic or cheating motives.

This fractured institutional structure, however, continues unchecked in India. Currently, the process allows bankruptcy filing only for corporate firms and individuals who are personal guarantors to credit defaulting firms. Like any new policy, the new code has several drawbacks and it has already been amended multiple times in the last five years. The uptake, too, has been quite slow.

There are a number of issues with the current draft. Renuka Sane, at the Indian Institute of Public Finance and Policy, highlights the key concerns as vague language around the definition of assets and income, little information regarding the proposed repayment plans and the fees that would be involved in the filing process. Moreover, the Debt Recovery Tribunal and the judicial system in general are already overburdened even though execution and implementation matter a great deal if the measure is to be saved from the inefficient bureaucratic nexus.

An operational bankruptcy code would not be a panacea solving all the problems of the current farm debt crisis, urban insolvencies or the amassing Non-Performing Assets of the governments banks. There has also been a long debate about the appropriate leniency of the laws to prevent them from abuse. But in the current Indian situation, apart from the extremely wealthy individuals who are able to game the system, much of the population is without any sort of insolvency relief. Occasional debt-relief packages are neither a systematic policy nor sufficient to comprehensively deal with the crisis. Hence, the impacts of the currently prescribed code need to be debated and analysed urgently. While it might take a long while to get a proper benefits programme for the vast majority of the population in India, a functioning bankruptcy code could provide much needed relief.

Banner Image: Photo by Jasper Garratt on Unsplash.

The views expressed here are those of the author and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.