The German model of “Kurzarbeit”, or short-time work, has proven to prevent the loss of jobs in a rapidly contracting economy, having found increasing purchase worldwide. Skilled jobs require specialisation and by avoiding lay-offs, the model could offer the Indian economy a means to stay resilient. Feroza Sanjana explains how adopting short-time work would help India seize the opportunity to catch up with China, and turn the pandemic into an economic opportunity.

Covid 19 and India Inc.

Covid-19 has dealt a major blow to India’s flailing economy. Even before the pandemic struck, India’s unemployment rate was estimated at a staggering 45-year high. The health emergency is predicted to push an even larger section of the Indian workforce into poverty and spiraling debt, with an additional 136 million non-agricultural jobs set to be lost as per recent projections.

These job losses will have dire consequences for Indian industry. The first relief package announced by the Indian government focused on providing cash transfers and food handouts, as well as footing contributions to employee provident funds, and the second offered a stimulus largely to Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) through collateral free loans. However, none of the measures introduced offer precise steps to avoid job losses to the skilled workforce — which is particularly striking given that MSMEs themselves employ skilled labour and also rely on demand from numerous specialised industries like aviation, manufacturing and hospitality. Those laid off will have to start the job search all over again, prolonging their hardship. On the flip-side, businesses already in the throes of liquidity problems will face additional costs of recruiting new employees, and delaying economic recovery.

Policy interventions amid Covid-19 should build resilience for both workers and businesses. One suggestion worth considering is the German model of “Kurzarbeit”.

The “Kurzarbeit” Model

“Kurzarbeit” or “short-time work” is a system introduced by the German government at the start of the 2008 financial crisis where, in instances of economic hardship owing to unavoidable circumstances, the government allowed companies to apply for permission for short-time work status. Under this provision, companies either asked their employees to stay home or reduce their working hours considerably. Employees still received a major part of their income during this time — in the German case, up to 60% of their salary, largely subsidised by the government.

Kurzarbeit has been touted as one of the reasons why Germany emerged relatively unscathed from the 2008 financial crisis. An OECD cross-country analysis of 16 countries which adopted short-time work during the crisis showed that 235,000 and 415,000 jobs were saved in Germany and Japan respectively, owing at least partially to the introduction of short-time work. A more recent study analysing firm-level data in Italy suggests short-time work helped to significantly stabilise employment and enabled firms to recover faster once the financial crisis was over. Countries worldwide have adopted the model or similar versions of it – including many across Europe and most recently, the UK which announced its Kurzarbeit-esque furlough scheme.

In response to the current Covid-19 pandemic, the German government has brought back what it calls its “protective shield”, this time to cover even more workers. In contrast to the earlier requirement of at least one-third of the workforce being adversely affected to be eligible to apply for the scheme, Berlin has now lowered the national threshold to 10%, and widened its scope to include temporary workers.

The Indian Context

Introducing short-time work could add teeth to India’s current relief package. By allowing skilled workers to receive part of their salaries, it will allow people to meet basic food, shelter and healthcare expenses. Putting employees on reduced hours does away with retroactive compensation in case of absence or termination of employment, and instead preserves existing employer-employee relationships.

For business, retaining their skilled workforce can help them recover faster in more affluent times. There are pay-offs for the economy too since unemployment figures would not rise as drastically. Additionally, given that reviving consumption is already a key challenge in the 2020-21 Union Budget, preventing the workforce from falling into debt or from breaking into their savings during the lockdown is also likely to prompt consumer spending once the virus retreats.

A Disruptive Paradigm

Admittedly, the financing of such a scheme is far more fiscally prudent for countries where their commitment to universal social security means that they face a far less thorny choice between paying unemployment benefits and reduced salaries on short-time work — which, in Germany, roughly amounts to the same, making it cost-neutral. In the Indian case, however, the lack of universal social security coverage would no doubt entail a short-term burden on the government’s purse strings and a far-reaching investment for the future.

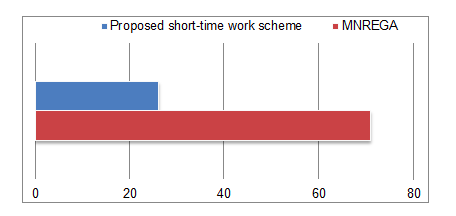

Cost of Existing Employment in Comparison to earlier Budgets (2019-20)

Source: Union Budget of Government of India, 2020-21. © Author.

To estimate the costs in India, one can focus on sectors that are currently taking a serious hit, particularly tourism, manufacturing and aviation, each estimated to lose jobs to the tune of 40 million, 9 million and 600,000 respectively. Since the aim is to ensure workers can make ends meet without losing their jobs or searching for alternative employment, a useful proxy is the daily national minimum wage as per the Code on Wages 2019 currently set at INR 176 per day. Assuming that one-third of the total expected job losses in the abovementioned sectors are highly specialised (roughly 16.5 mn jobs), this would mean that a short term work scheme to prevent layoffs would cost at least INR 8,712 crore or US$ 1.16 bn per month for all expected skilled jobs lost, excluding set-up and administrative costs. If the scheme was in place for 3 months, this would mean a total expenditure of INR 26,136 crore or around 0.9% of the entire national budget for FY 20/21 — making the scheme as a one-time expense — certainly within reach.

The payment of salaries of high-skilled employees who would otherwise be laid off could be financed by direct transfers by the government and/or via collateral-free loans provided to employers. Skilled contract workers salaries could be supported by the Corporate Social Responsibility Fund (CSR), not at all too different from allowing CSR spending towards a social security corpus for temporary employees since September last year. Alternatively, Indian employers could be encouraged to participate to co-finance the scheme.

Ultimately the preference for short-time work over lay-offs is rooted in a different paradigm of government and corporate social responsibility which is not mere philanthropy but rather the idea that government and businesses are responsible for safeguarding the human rights of their own workers, whether they be permanent or temporary. While there has been a perceptible shift in thinking that India, strengthened by positive and progressive steps such as the Corporate Social Responsibility Rules 2014 under the Companies Act 2013 and the ongoing finalisation of the National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights, there is still much to be done.

In line with this alternative paradigm, Kurzarbeit offers a valuable tool to protect vast swathes of the Indian workforce against a crisis of no small magnitude. Failing to soften the blow during the coming months will not only cost jobs to Indian industry which are unlikely to bounce back in the near future but will also make it extremely difficult for the country to stimulate demand once the lockdown is eased. The Ministry of Finance and the Niti Aayog should take note of positive evidence on the benefits of Kurzarbeit. Industry leaders and policy-makers need to urgently engage in policy initiatives — to turn the pandemic into an economic opportunity.

© Photograph: “At work, Mumbai”, Jeet Dhanoa, Unsplash.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of South Asia @ LSE blog, nor the London School of Economics and Political Science.