Film magazines offer a unique lens to appreciate a culture of expression pertaining to film censorship concerns in Bangladesh. In this post, Arpana Awwal traces some of the censorship debates in archived film magazines Chitrali and Purbani between 1981–1991.

Film magazines offer a unique lens to appreciate a culture of expression pertaining to film censorship concerns in Bangladesh. In this post, Arpana Awwal traces some of the censorship debates in archived film magazines Chitrali and Purbani between 1981–1991.

Regardless of the fact that files of censored films remain restricted to public access in Bangladesh, archival materials such as film magazines chronicle pulsating conversations on film censorship that amount to moral panic, blame games, breaking laws, bans, court cases, and what not. The Bangladesh Film Censor Board (BFCB), which functions under the Ministry of Information, is a governing body that inspects and monitors motion pictures. Though amended, Bangladesh’s Film Censorship Code is modelled on the censorship laws introduced by the colonial British administration in the Indian subcontinent in response to growing nationalist sentiment at the time. Studies suggest that film as a medium was considered as potentially enticing and inciting the colonised subject as early as in British India. Even today the most heated discussion on film censorship in Bangladesh is governed by the rhetoric of ‘obscenity’, ‘morality’, ‘nationalism’ and ‘violence’. In this post I touch upon some of these issues with regard to specific genre films in Bangladesh’s popular Bengali-language film magazines Chitrali and Purbani from 1981 to 1991.

On 21 April 1983, Purbani (p. 12) published the following message sent by one of its readers:

There is no audience for good cinema. There is a dearth of healthy films. There are no viewers of healthy films. Since they don’t want to watch healthy films, producers and directors are making action and fantasy films (all translations from Bengali by author).

The message conveys a common line of perception that polarised good and healthy films against action and fantasy films. What is apparent in the magazines is the ostracisation of action and fantasy films on grounds of violence and ‘obscenity’, two terms that are used extensively. It is worth mentioning here that although there were import and projection bans on Indian and Pakistani films in Bangladesh, the introduction of new technologies (like VFS and VHS) in the early 1980s gave people access to foreign films of all genres, including action and fantasy. Small venues that housed projections of foreign films, including pornography, soon became very popular. Complaints by filmmakers in this context reveal the irony in BFCB’s stringent method of examining genre films (Purbani, 17 November 1983, p. 6). Magazine reports also echo BFCB’s laxity in scrutinising ‘indecent’ and ‘violent’ images in costume/fantasy films based on the logic that ‘because fantasy-based films have little connection with reality, they are less likely to affect the general viewers’. One film director commented, rather sarcastically, that ‘thanks to the Censor Board we will have a new definition of vulgarity’ (Purbani, 17 November 1983, p. 6). Curiously, words such as ‘obscenity’, ‘indecent’, ‘immorality’, ‘violence’, ‘culture’, ‘tradition’, though mentioned in the Censorship Code, are not defined. And of course, this gap allows both parties, the Bangladesh Film Development Corporation (BFCD) and BFCB, to produce their own conflicting interpretations. The Censorship Code also presents a peculiar and dichotomous condition when it states (in Clause IV(j)) that scenes of semi-nudity and intimacy may be shown in foreign films but not in those made in Bangladesh. One can begin to see how the leniency in identifying the ‘vulgar’ in fantasy films was based on the belief that human ‘fantasy’ was outside regular norms and conditions because of its extraordinary content.

At different points statements made by officials give a sense of how the government perceived the role of the film industry in society. The Deputy Minister in the Ministry of Information, suggested that the ‘people in the film industry must learn from the ideals of Jahir Raihan’ (Chitrali, 5 February 1982, p. 3). Jahir Raihan, journalist, writer, a pioneer film-maker and freedom fighter, is seen as a symbol of nationalism. Given that new technologies were seen as competition, the Information Minister warned that ‘one must not make vulgar films in an attempt to capture the market’ (Chitrali, 12 February 1982, p. 3). At the same time, people outside the ministry had a different view on the matter. Magazine reports suggest the inaction of the Censor Board regarding plagiarised films (Purbani, 20 October 1983, p. 10). In a similar vein, actor Alamgir points to BFCB’s negligence in film inspection and claims that the institution alone is responsible for clearing films of low-quality which leads to further production of poor-quality films (Purbani, 18 October 1984, p. 5). Similar concerns were expressed by general readers like Md. Didarul Alam and Shahidul Alam who penned a letter titled ‘Copy films and Censor Board’ in Purbani (8 September 1983, p.12). On 1 November 1984, another news item quoted the Information Minister declaring that the Censor Board would not clear costume, action and ‘bizarre unrealistic’ films (Purbani, p. 3). In response, Kamal Parvez, the General Secretary of Bangladesh Film Distributors Association, voiced his angst against such laws which blackball certain genres and will cause major setbacks in the industry (Purbani, 4 October 1984, p. 4). Such conversations resonate concerns similar to those of the British in colonial India about the ‘excitable’ power of the visual and, therefore, the need for ‘healthy’ and ‘educational’ cinema.

While these news items are telling of the antagonistic relation between BFDC and BFCB, Parvez’s stance that besides ‘healthy’ and ‘educational’ films there is need for films to entertain points to a larger question of film’s role in society. His remark is suggestive of popular films as separate from, or even the opposite of, ‘educational’ and ‘healthy’ ones. Similar to ‘obscene’ and ‘vulgar’, there is no clear definition of what is ‘healthy’ and ‘educational’. For the Censor Board the terms can be interpreted in any number of ways, and so can they be for film-makers. Moreover, while there is a perpetual attempt to curb indecent images in reference to nation, culture and morality, such repetitive discourse makes sexuality even more existent. Following Michel Foucault’s ‘repressive’ hypothesis one can argue that a pervasive moral panic reflects obsessive references to the ostensibly forbidden subject.

In an interview, actor Alamgir’s statement that the Censor Board could only reject his film if it had anti-state elements (Purbani, 18 October 1984, p. 5) is indicative of a deeper concern about how the state, nation, and citizenship was generally understood within the larger socio-political setting during the presidency of Hussain Muhammad Ershad (1982–1990). Censorship of political content was not limited to films alone. The Censor Board, during Ershad’s time, rejected many TV dramas and edited scenes with political messages: to cite an example would be the two edits in the TV drama Protikkhar Prohor (Hours of Waiting) for reasons of seditious content (Purbani, 3 January 1991, p. 13). But that is not all. There prevailed an overarching tension over the genre of historical films, especially war films, one that can be traced back to the time of Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman (1977–1981).

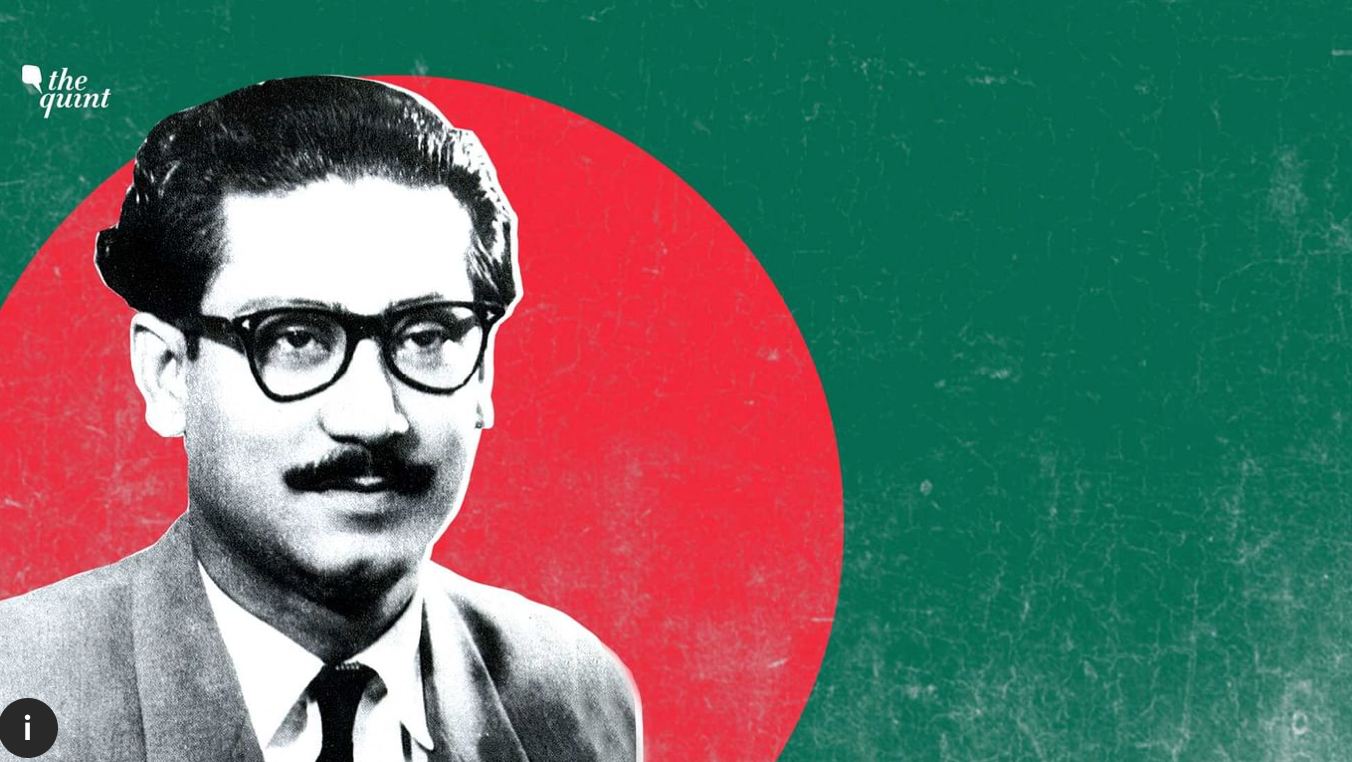

Photo 1: A feature titled ‘The death of President Zia brought a dark cloud of grief over the film industry’, Inset photo of Ziaur Rahman, Chitrali, 5 June 1981, p. 5. © Chitrali; used with permission of author.

War films did not sit well in Zia’s regime, which is why ‘producers [did not] consider making war films’ (film director Subhash Dutta, Chitrali, 27 March 1981, p. 5). What began as an amnesia in the production of war films during Zia’s government can be read as the genre’s conflict with the new set of nationalist ideologies that Zia was propagating. Feature stories in the magazines imply that throughout his regime, state politics was a deciding influence in shaping film narratives, self-censorship in filmmaking and political groupings of film-makers to curry favours from the government (Chitrali, 27 March 1981, p. 5). Within this context, one is not surprised to read Parvez’s comment that the ‘Indian Censor Board gives clearance to films on social and political themes which would never be possible for us.’ His other comment on the failure of law enforcement agencies in preventing illegal exhibitions of pornography across the country and the Censor Board’s inaction against the exhibition of Pakistani and Indian films in cinema halls in certain élite areas (Purbani, 4 October 1984, p. 4) brings forth two sets of paradoxes. The first paradox lies in the strict scrutiny of BFDC films for ‘obscenity’ but inefficiency in controlling the viewing of pornography; and the second one is on the issue of nationalism, especially given Bangladesh’s history with Pakistan and the projection of Pakistani films in government venues while being officially banned.

Photo 2: Actor-turned-Politician Kobori (left) with Sheikh Hasina (right; current Prime Minister of Bangladesh, and leader of Bangladesh Awami League party). The title reads ‘Hasina Wajed and Kobori: Two Stars of Two Different Skies’, front page of Chitrali, 16 September 1983. The actor joined Bangladesh Awami League and served as an elected member of the parliament from 2008–2014. © Chitrali; used with permission of author.

The 1990s brought a wave of change and hope with Bangladesh’s politics moving towards a democratic government. This change was also reflected in the release of the film Linja (1991) which was not certified by Ershad’s government because of its potential to stimulate a movement against the regime, said Dewan Nazrul, the producer of Linja (Purbani, 14 February 1991, p. 4).

Photo 3: A report featuring the news of the release of Linja with a still from the film. Source: Purbani, 9 May 1991, front page; © Purbani; used with permission of author.

Linja showcased contemporary social realities in the absence of democratic governance. The wide coverage of the censorship of Linja in magazines is an important referent of the intersection between the public, political, popular and censorship. Much like the mass movement that brought about the end of Ershad’s dictatorship, Linja was released on face of substantive pressure from Chhatra Oikka or Sarbadaliya Chhatra Oikkya Parishad (an alliance of student political parties formed in 1990 that gave force to the anti-Ershad movement) (Purbani, 9 May 1991, front page). Further demands were being made from the new government to release previously censored films and TV dramas. G. M. Hamid, theatre personality and producer at Bangladesh Television, for example, was demanding that the Censor Board under the new government clear four television dramas that had been blocked in Ershad’s time, three of which were based on Bangladesh’s War of Liberation in 1971. This demand echoes the long absence of war films and dramas.

Photo 4: Front page of Purbani, 7 February 1991 covering news of the upcoming elections. It shows Sheikh Hasina (left), current Prime Minister of Bangladesh and daughter of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman), and Khaleda Zia (right), Chairperson of Bangladesh National Party and widow of late Ziaur Rahman; © Purbani; used with permission of author.

Such intense engagement with political developments in film magazines suggests that the political is never very far from the popular. On 3 January 1991 a report featured a list of actors, producers and directors who were looking forward to political candidacy in the coming election (Purbani, p. 3). Every issue had some news item on the political climate of the country. That the front page of Purbani published a feature on the manifestos of the two political parties, Bangladesh Awami League and Bangladesh National Party, for the then upcoming election (Purbani, 7 February 1991) reveals the intimate relationship between the film industry and national politics. The preoccupation of politics in popular film magazines indicates the film industry’s dialogue with the larger politics.

The lens of the censorship in reading film magazines does not only reveal socio-cultural ideologies but also ideologies of shifting political changes. On the question of ‘obscenity’, one begins to see a pattern of formulaic and static, but also vague, sense of what is morality, culture and tradition. Yet, curiously, the features also reveal nuanced ways in which nation, state and sexuality are understood. Moreover, there is an awareness that nationalism is obliquely bound up with a sense of morality and responsibility of the film industry.

*

This article gives the views of the author and not of the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics & Political Science.

© Banner image: ‘Cinematographer’s Room’ by Noom Peerapong, Unsplash.

The ‘Bangladesh @ 50’ logo is copyrighted by the LSE South Asia Centre, and may not be used by anyone for any purpose. It shows the national flower of Bangladesh, Water Lily (Nymphaea nouchali), framed in a design adapted from Bangladesh’s dhakai & jamdani textile weaves. The logo has been designed by Oroon Das.

*