Last month, India’s job crisis gained world attention when young applicants rioted against the alleged lack of transparency in the recruitment process of Indian Railways – one of the biggest employers in the country. Despite having a very large working-age population, and even during periods of marked economic growth, India has long suffered from intractable youth unemployment, which has been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing on key labour statistics, Radhicka Kapoor draws out the structural nature of the problem, and suggests reforms needed to correct this anomaly if India is to reap its long-promised demographic dividend.

The violence that erupted recently in the populous states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (U.P.) as angry job aspirants protested against the Ministry of Railways’ recruitment examination has brought India’s job crisis to the centre of the economic policy debate in the country. However, this crisis is not new. It has been long in the making.

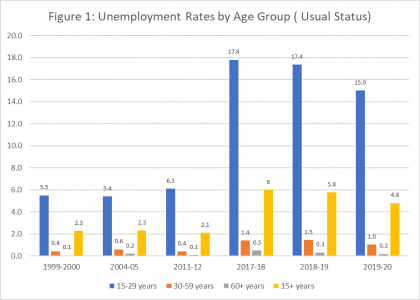

In 2017–18, the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), a household employment–unemployment survey providing annual estimates on key labour market indicators, reported a 45-year high in India’s open unemployment rate of 6.1%. What was particularly alarming was that this statistic was largely a consequence of high unemployment amongst the youth, i.e. those in the 15–29 age bracket. The aggregate youth unemployment rate stood at 17.8% and has remained at above 15% in the period 2017–2020.

While the youth unemployment rates observed over the last three years are considerably higher than those witnessed ever before, it is noteworthy that even in earlier employment–unemployment surveys, the unemployment rate amongst the youth has been significantly greater than all other age groups (Figure 1).

Source: Data from PLFS and NSS Employment–Unemployment Surveys (several years)

What is more, a disaggregated analysis of trends across the youth by education levels shows that unemployment rates rise with education levels. In 2018–19, before the pandemic struck, the unemployment rate amongst the educated youth (defined as those having secondary education and above) stood at 24.5% compared to 7% amongst those with primary education only.

Given these statistics, it is no surprise that the fact of highly-qualified candidates applying for low-level jobs was one of the drivers of the recent disturbances in U.P. and Bihar. Amongst the 12.5 million candidates, who had applied for the 35,281 job openings in ‘non-technical popular categories’ (typically considered low-end jobs), many had college degrees. In fact, some of the protesting applicants felt that the Railways were biased towards candidates with college degrees, shortlisting them even for jobs where the minimum requirement was lower. The widespread joblessness amongst the educated youth, therefore, created fears amongst the less educated that they would be crowded out of even low-end jobs.

The phenomenon of higher unemployment amongst the educated youth is not a recent phenomenon. A time series analysis of earlier employment–unemployment surveys shows that the educated youth have typically reported a higher unemployment rate than other age- and educational-groups. As far back as1959, Professor K.N. Raj had pointed to the high open unemployment rate amongst the educated youth and cautioned that India’s future lay in the quality of jobs generated for its youth. The challenge has dramatically exacerbated over time as the Indian economy has failed to generate adequate employment opportunities outside the agriculture sector for its rapidly rising young population, which has been becoming increasingly educated over time.

However, it is important to note that the clamour for Railways’ jobs is not just about the disillusionment amongst the youth due to their inability to find jobs. It is also about their inability to find ‘good jobs’ that offer them security of tenure, earning stability, access to social protection schemes and career advancement opportunities. In 2018, too,19 million candidates had applied for 63,000 vacancies with the Indian Railways.

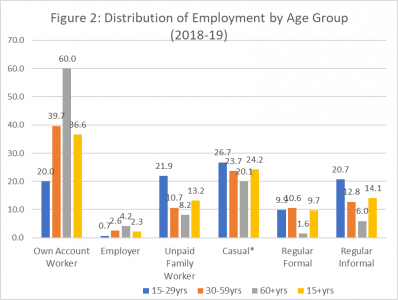

Given the nature and quality of youth employment, this is unsurprising. Using the most recent PLFS data for the pre-pandemic period (2018–19), it is observed that over one-fourth of employed youth were engaged as casual labour (Figure 2). One-fifth were working as unpaid family workers/helpers in their household enterprises – they were working full- or part-time but did not receive any regular salary or wages in return for the work performed. Only 10% were engaged in regular salaried work that provided access to social security benefit (referred to as regular formal employment).

Jobs which provided security of tenure were few and far between. Amongst the youth engaged in regular salaried work, over 78.3% had no written contract and a mere 11.3% had contracts for more than three years. In contrast, in the older cohort of 30–59 years, the quality of regular salaried work was comparatively better, with the share of regular salaried workers who had no written contracts was 65.6%, while the share of those who had contracts for more than three years was 26.5%.

Source: Data from PLFS (2018-19)

Note:* A person who is casually engaged in others’ farm or non-farm enterprises (both household and non-household) and, in return, receives wages according to the terms of the daily, or periodic, work contract is considered casual labour.

Given the precarious nature of their job contracts, it is unsurprising that post-pandemic the youth have borne a disproportionate burden of the job losses. Many of them have found themselves pushed to work as unpaid family helpers with the share of this group of workers in 2019–20 rising to 25.3% – a 3.5 percentage point increase over the previous year.

Significantly, the two states, Bihar and U.P., where the violence was witnessed account for the largest share of youth in India – Bihar accounted for 7.9% and U.P. for 17.2% of all 15–29 year olds in India. However, both states perform particularly poorly in terms of quality of employment. In Bihar, a mere 9.6% of the youth had regular salaried jobs. In U.P., the corresponding share was 15.2%. What is more, 58.4% and 65.7% of the youth in Bihar and U.P. respectively were self-employed, working predominantly in agriculture. The lack of adequate employment opportunities outside the agriculture sector, which is reflected in the low shares of employment in the industrial sector (particularly the manufacturing sector which accounts for only 4.75% of total employment in Bihar and 11.1% in U.P.), have compelled many frustrated job-seekers to look for government jobs.

The above facts pertain to only those individuals who are in the labour force and are actively seeking employment. They, therefore, provide only a partial view of the extent of challenges faced by the youth in India. A key statistic to examine for this cohort is the share of youth who are Not engaged in Education, Employment or Training (NEET), i.e. those who are not engaged in any productive activity.

In 2018–19, an alarming 34.5% of the youth were in the NEET category. Significantly, this ratio has been over 30% in all employment–unemployment surveys since 1999–2000 suggesting that almost one-third of India’s young are idling away their lives indulging in what Craig Jeffrey described as “timepass” (just passing time) . These trends appear to be a consequence of multiple factors.

One, there are not enough quality jobs being created for the young. Two, they have very few incentives or they face too high constraints to be in education and training. And three, the transition from school to work is by no means smooth.

There is no silver bullet for addressing these challenges. However, as India’s young seem dangerously out of patience in their wait for decent and gainful employment, policy support to young people including employment services, active labour market programmes (such as hiring subsidies) and entrepreneurship schemes need to be examined urgently. The inability of young adults to secure good jobs at the cusp of their career is not only demotivating and discouraging for them but can also lead to a scarring effect on their career with a higher likelihood of being unemployed later in life and a wage penalty. For society, growing youth unrest may be the price to pay.

Banner Image: Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash.

The views expressed here are those of the author and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.