Solid Waste Management affects each and every individual on the planet. This is of particular relevance in the developing world where increasing population, urbanisation and lack of resources very often make city life unclean, unhealthy and hazardous. Climate change has exacerbated these issues. On the occasion of Earth Day, Mani Nepal and A.K. Enamul Haque discuss the findings of their study, in two cities of Nepal and Bangladesh, that successfully identified the main challenges faced by city administrations in tackling the issue, and impacted on the policies adopted.

Every year, most cities in South Asia experience waterlogging, especially during monsoon. Streams of dirt and debris run through streets, and temporary water bodies are formed due to waterlogging (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Waterlogging in Banepa, Nepal (Photo: Himal Khabar, 6 March 2022), used with permission.

The first obvious reason for this seasonal waterlogging is a poor stormwater drainage system. This means that the rain water has no proper route for being drained from the ground’s surface. Many cities in South Asia are built on filled-up, low-lying land or on agricultural land, and city planning bodies have failed to invest adequately in the drainage system.

However, there are other reasons too. Climate change is a big contributor. It triggers intense and frequent rainfall events that overwhelm urban drainage systems. Indiscriminate dumping of solid waste in urban settlements, which clogs the drainage system, is another reason. This dumping is specifically a behavioural issue that involves how cities manage their solid waste and to what extent citizens cooperate with civic bodies to dispose their waste (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Waste dumping (Photo: Research team)

Our study

To understand the linkages between municipal solid waste management and the waterlogging issue in urban areas, a study – entitled “Cities and Climate Change” – was conducted in Bharatpur (Nepal) and Sylhet (Bangladesh). The study, conducted between 2017 and 2020, used various methods including hydrodynamic modeling, hedonic price model, randomized controlled trial, and choice experiment.

The transdisciplinary research team included economists, urban planners, gender experts, GIS experts, modellers, hydrologists, engineers, and land-surveyors. In this article,

we discuss the key lessons from our research focusing on factors that increase the risk of waterlogging in urban areas, ways to reduce such risk, other benefits to city residents from better municipal solid waste management, and financing waste management activities in cash-strapped cities.

Investment in drainage infrastructure alone not enough

Investment in constructing a city’s drainage system is often considered a solution to the problem of urban waterlogging. We collected field data covering a wide range of factors and methods (Figure 3) to understand the current capacity of the stormwater drainage systems in Bharatpur and Sylhet.

We considered various scenarios to understand the implications of extreme climate events, including

high-intensity, short-duration rainfall events, which are a major cause of waterlogging in these cities.

Figure 3. River cross-section and land-level data collection (Photo: Research team)

The study found that:

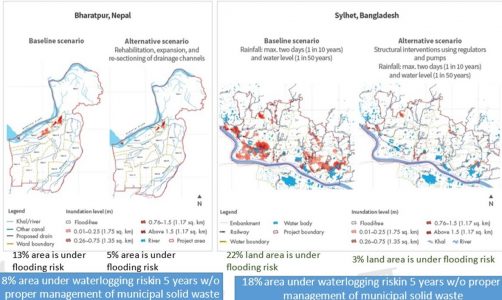

- given the existing drainage infrastructure, about 13% of the land area in Bharatpur and 22% of the land area in Sylhet are currently at waterlogging risk from extreme climate events (Figure 4);

- investing in the construction and expansion of the drainage infrastructure would bring down the area under flood risk to 5% and 3% in Bharatpur and Sylhet, respectively.

Our study predicts that

- if current waste management practices in these cities continue, a significant amount of waste will end up settling in the drainage system, which would reduce the depth of the canals and drains by over 10 cm per year. Subsequently, in five years, the areas at flood risk would revert to 8% in Bharatpur and 18% in Sylhet;

- this reduces the returns from investment in the drainage infrastructure. As such, attempts to reduce the risk of flooding by

investing in the drainage infrastructure alone would be unsustainable without proper municipal solid waste management.

Figure 4: Baseline and improved scenarios of waterlogging in Bharatpur and Sylhet (Source: Pervin et al. [2020]])

Current waste collection system unsatisfactory

In Bharatpur, residents pay NPR 30–100 (~USD 0.25–0.8 in 2018) per month for waste collection services depending on the frequency of collection per week. Over 50% of residents in Bharatpur expressed dissatisfaction with the existing practice of waste management.

There is a lack of synchronisation between the time households put their waste out and the time the waste is collected for disposal. Most of the waste, therefore, gets scattered on the streets (by scavenging animals or scrap material collectors) and finally to the drains.

City dwellers in Bharatpur are ready to pay an extra fee between 10% and 28% to support waste management services. However, our back-of-the-envelope cost–benefit analysis suggests that the additional revenue is not sufficient to finance the additional services for synchronised collection of waste and keeping the streets clean.

Separating waste at source and composting reduce collection and transportation costs

In Bharatpur and Sylhet, much of the household waste produced is organic and biodegradable. However, most households do not segregate the waste properly and dump it all in one basket, which goes to the landfill.

In our study, we motivated three local clubs in Sylhet to promote community-based composting of kitchen waste on a pilot basis, where over 90% of the waste is biodegradable. This was the first composting pilot in the city that demonstrated how compost fertiliser could be produced from biodegradable household waste and used in kitchen gardens and elsewhere.

Bharatpur promotes subsidised composting at the household level. However, if more households are interested in the composter, the city will not be able to bear the cost of the subsidy.

Since much of household waste is biodegradable, at-source segregation and composting would reduce the volume of waste by 70%–90% in these cities, resulting in drastic reduction in waste collection and transportation costs.

With less waste going into the landfill, the lifespan of landfill sites would extend.

Once segregated, items such as metal, paper, and plastic could be collected and recycled, generating additional revenue. The concept of a circular economy, if enforced properly, can help reduce waste management costs and generates revenue from recycling.

Therefore, the absence of proper management of municipal waste in South Asian cities is not just because of a lack of resources; it is mainly because of the lack of management plans and effective implementation.

This learning is useful since at-source waste segregation and composting is easily replicable in other cities.

Cities can improve property tax base and generate resources by investing in municipal waste management

In another study of ours, in 58 urban areas/cities across Nepal, we found that urban residents place a higher value (by 25% or more compared with those areas without such a service) on their housing property, if the community had waste collection services. We also found that in neighbourhoods where the community is exposed to open drains, the self-assessed housing value goes down by 11%, suggesting that the city can enhance its property tax base by investing in municipal waste management.

When housing property prices appreciate due to better management of municipal solid waste, cities could generate more resources from property tax without increasing the tax rate.

Such additional resources could be sustainable if cities develop and execute such policies effectively.

Further, since plastic waste is a serious concern in South Asia and globally, resources can be generated by imposing additional tariffs on plastic raw material that is used to produce single-use plastic which goes to the landfill or pollutes the environment. Such a tariff would also make single-use plastic items expensive and increase the value of recyclable plastic, thus promoting recycling while providing incentives to replace single-use plastic bags with locally available substitutes. These substitutes (such as cloth or paper bags), if locally produced, could support the local economy through employment generation.

Simple low-cost interventions could make cities cleaner

Our research on evaluating the impact of two low-cost interventions found that awareness-raising on the importance of managing waste properly, and placement of low-cost small waste bins on the streets (Figure 5) could help keep the city streets cleaner.

Further, after being sensitised to the issue, women waste managers perform well in segregating waste at source and composting degradable waste, although they do not seem to do as well with regard to managing plastic/paper/metal waste after segregation, probably due to lack of market information. We found that informing women about the price of recyclable waste in the local recycling market is effective in reducing the volume of recyclable waste that ends up in landfills.

Figure 5: Low-cost interventions: (Up) information dissemination and (Down) street waste bins (Photo: Clean Up Nepal [field partner in the research project] and SANDEE)

Use of mobile app could reduce waste burning, dumping, and littering

Our field partner Clean Up Nepal developed and deployed a pilot mobile application – Nepal Waste Map – in a ward in Bharatpur to assist relevant stakeholders in collecting and disposing municipal solid waste. With the use of this mobile app, instances of waste burning, dumping in open spaces, and not collecting waste from households reduced significantly. ACD developed a similar mobile app and used it in Bangladesh with similar results, suggesting that

the use of technology helps keep cities cleaner.

Figure 6: Mayor of Bharatpur launching the mobile app (Photo: Research team)

The study’s policy impact

The research was planned jointly with relevant stakeholders and city officials, who were constantly appraised on the activities and progress (Fig 7). Due to such collaboration, Bharatpur Metropolitan City introduced a policy to segregate waste at source and manage it properly. However, the absence of a landfill site for properly disposing of the segregated waste and composting facility for managing biodegradable waste are impeding the successful implementation of this policy.

Our collaboration also led the Government of Nepal to ban single-use plastic bags less than 40 microns thick from production, import, and use starting from 16 July 2021. However, the policy is yet to be implemented due to the change in government in July 2021.

Figure 7: Study visit of city officials to other cities: (Up) observing waste management in Dhankuta, Nepal, and (Down) observing a waste-to-fertiliser plant in Ilam, Nepal (Photo: Research team)

In Sylhet City Corporation, the announcement of a green club award mobilised volunteer efforts by local clubs to make their neighbourhood cleaner. Since Sylhet is a popular tourist destination in Bangladesh, the project has been able to secure buy-in from the city’s mayor (Fig 8) for community-based awareness-raising campaigns to promote composting of waste from homes and businesses. The city corporation further requested the research team to study possibilities of managing restaurant and vegetable market waste in a similar way.

Figure 8: Sylhet City Corporation Mayor speaking at the Green Sylhet Award Ceremony on 28 April 2019 (Photo Credit: Asian Center for Development)

SEE MORE AT

- A short video that summarises the key findings of the research can be found here

- Adapting to urban flooding: A case of two cities in South Asia

- Making waste management and drainage sustainable in Nepal

- Improving municipal solid waste collection services in developing countries

- Sustainable financing for municipal solid waste management in Nepal

- Value of cleaner neighbourhoods

- Waste segregation at source for reducing water logging

- Low-cost strategies to improve waste management

- What makes a ban on plastic bags effective?

Acknowledgement: The International Development Research Center (IDRC) provided financial support for this research (Grant #08283-001) under the Cities and Climate Change research project (2017-2020) to conduct this study. The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable support provided by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICMOD) and its core donors – the Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Sweden, and Switzerland – towards implementing the research project.

Disclaimer: The views and interpretations in this publication are those of the authors. They are not necessarily attributable to IDRC, ICIMOD or East West University, and do not imply the expression of any opinion by ICIMOD or the University concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area of its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or the endorsement of any product.

Banner Image: Photo by Johaer on Unsplash.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.