Nepal’s civil war ended in 2006. The post-war political transition has opened up opportunities to increase the political representation of marginalised and disadvantaged groups. While representation of women and of disadvantaged caste/ethnic groups in Parliament has increased significantly, the simple numerical data tells a partial story. Behind the ostensibly representative political institutions, new practices perpetuate the dominance of male high-caste elites. Jayanta Rai looks at the role played by the Constituency Development Fund in this process.

The issue of inclusive political representation has been central to the post-war political debate in Nepal, after the end in 2006 of a ten-year long war between the state and Maoist rebels. The demands for political inclusion of historically excluded caste/ethnic groups, championed by the Maoists during the conflict and in the post-war period, were translated since the Interim Constitution of 2007 into formal political institutions that increased representation through a system of quotas. The new Parliament, and the two Constituent Assemblies before it, were the most diverse in the history of the country, with unprecedented proportions of women and of representatives from disadvantaged groups.

However, the changes brought by the war have failed to transform the underlying configurations of power and their impact on political inclusion has been limited by the continued dominance of traditional elites. In a recently published article, I have looked at the

Constituency Development Fund (CDF) as one example of how privileged high-caste groups have managed to twist the working of apparently inclusive formal institutions to cement their political and economic dominance.

First-class and Second-class MPs

It has been argued that, in countries transitioning from conflict, political representation of ethnic, religious and regional groups in parliament through a proportional system contributes to resolving conflict and establishing a stable peace. Looked in this perspective, the achievements of post-war Nepal are remarkable.

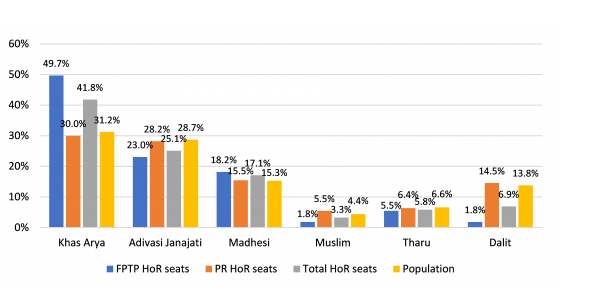

The 2015 Constitution mandates that 40% of the members of the House of Representatives be elected through a proportional system, with separate quota for six caste/ethnic groups that reflect their respective shares of Nepal’s population. There is also an overall quota for women. As a result, the current Parliament looks much more inclusive than before the war: almost 33% of MPs are women (compared to less than 6% in the 1999 Parliament), and the proportion of MPs belonging to the politically dominant Khas Arya group (hill high-castes) has decreased from 58% to 42%, although it is still higher than their share of population (31%).

However, these numbers tell only part of the story. Much of politics remains dominated by the old Khas Arya elites and

new arrangements have been designed to perpetuate such dominance in the context of ostensibly more inclusive political institutions.

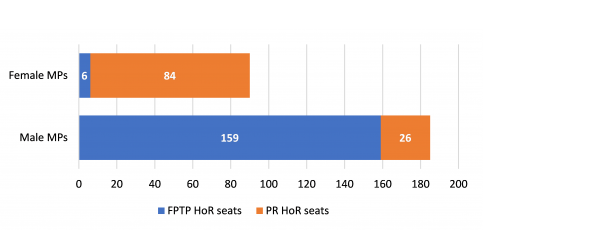

A closer look at the House of Representatives shows that not all MPs are created equal. The Parliament contains two different groups of MPs elected through two different systems of elections. Of the 165 MPs elected through a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, almost 50% are Khas Arya, reflecting the persisting dominance of this group within the leaderships of political parties; disadvantaged groups like Dalits and Muslims are particularly underrepresented; and only 6 out of 165 are women (see, Fig. 1), consistent with the patriarchal character of Nepali society.

Figure 1: Representation of caste/ethnic groups in the House of Representatives © Jayanta Rai

The design of the quota system results in the representation of historically excluded groups and of women (Fig. 2) coming mainly from the 110 MPs elected through the proportional representation (PR) system. In this context, institutions that limit the autonomy and power of PR MPs have the result of reinforcing the political dominance of the traditional male high-caste elites.

Figure 2: Gender composition of the House of Representatives © Jayanta Rai

The Role of the CDF

Until its recent suspension due to the COVID crisis, one of these institutions was the CDF, which allocated funds directly to MPs to be spent on development projects in their own constituencies. While CDF programmes have been criticised in the past as a source of corruption and inefficient use of resources, the way the scheme was designed in Nepal also reinforced historical patterns of political exclusion in access to resources.

The CDF grew in size in recent years, with increasing amounts being allocated to the members of the Constituent Assemblies (between 2008 and 2017) and then to MPs (since 2017).

The allocation, however, was different for FPTP and PR representatives.

FPTP members saw their funds increase from Rs 10 million in 2013 to Rs 60 million in 2019-20; each PR representative, on the other hand, only received around 1/6 of the amount until 2017, and nothing after the 2017 elections.

The difference in access to resources translated into a difference in representatives’ ability to strengthen their political base. Patronage is a crucial part of politics in Nepal, where political parties are mainly coalitions of informal and personalised networks linking powerful politicians to their supporters.

The CDF played a significant role in enabling MPs to acquire loyalties through the provision of local infrastructure and the choice of contractors.

The lack of similar resources made it difficult for PR MPs to create their own support base. This added to the perception by bureaucrats and in some cases voters that PR MPs are less capable of getting things done.

Given the sharp differences in the caste/ethnic and gender composition of FPTP and PR MPs, the system tended to cement the political dominance of hill high-caste men, while leaving female MPs and many MPs from historically excluded groups dependent, for their political career, on their parties’ leadership, itself mostly formed of hill high-caste men.

A Centralised Mindset

The other main change brought by the war and the post-war transition has been the establishment of a federal structure of government. Given the historically highly exclusionary character of the Nepali state, a federal reform was presented as key to addressing political, economic and social exclusion by facilitating the integration of groups marginalised by the centralised state and giving them a degree of autonomy over decision-making processes and access to resources. A federal structure was formally established by the 2015 Constitution – although without addressing many of the demands from marginalised sections of society – but its implementation has encountered many obstacles, the result of a political leadership with a centralised mindset and fearful of losing its traditional power.

The CDF played an important role in this effort to hinder the implementation of federalism and, in so doing, perpetuate a less inclusive political system. First, it changed MPs’ priorities: if people judge MPs by the development work they bring to their constituency, rather than by their parliamentary work, they have an incentive to disregard their duties in Parliament and spend more time in their constituencies. The absence of MPs has significantly delayed the approval of laws necessary to implement federalism. Second, the CDF perpetuated a centralised mindset according to which, if something is needed in a town or village, people go to their MP, rather than to their representatives in the local government, to which the Constitution gives authority over local development. This on the one hand delegitimises the new local political institutions, and on the other reduces the pressure they face to be accountable for their (lack of) action.

Beyond the Numbers

As the case of the CDF shows, political inclusion goes beyond the simple numerical data on representation in Parliament, or in other formal political institutions. A fuller assessment of the inclusivity of a political system requires an analysis of the interaction between institutions and the distribution of power and resources. Such analysis can reveal how apparently inclusive institutions can hide more subtle mechanisms through which the dominance of traditional ruling elites is maintained.

In the case of Nepal,

if we look at the actual exercise of power and access to resources, the political system looks much less inclusive than what formal representation statistics suggest.

The political settlement at the centre remains dominated by conservative forces, while political representation of disadvantaged groups failed to translate into substantial inclusion that could address their socio-political and economic grievances. This has also been reproduced in the newly created sub-national governments.

Banner Image: Photo by Sujitabh Chaudhary on Unsplash.

The views expressed here are those of the author and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre, or the London School of Economics and Political Science.