The General Elections of 1984 — following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in October — was a seismic event in Indian politics. Amogh Dhar Sharma examines the use of advertising and new technology, which played a novel and vital role in the elections that followed and brought her son Rajiv to the forefront, the first time political ‘marketing’ was consciously used by political parties so extensively as part of their electoral campaign.

The General Elections of 1984 — following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in October — was a seismic event in Indian politics. Amogh Dhar Sharma examines the use of advertising and new technology, which played a novel and vital role in the elections that followed and brought her son Rajiv to the forefront, the first time political ‘marketing’ was consciously used by political parties so extensively as part of their electoral campaign.

The Rajiv Gandhi years — from his formal induction in the Indian National Congress (INC) party in 1981 to the crushing defeat in the 1989 General Elections, followed by his untimely death in 1991 — are but a short period in the larger trajectory of Indian politics. Yet this all too brief period witnessed many significant developments: the ‘Shah Bano’ judgement, Bofors Scandal, the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), ascendance of regional parties, piecemeal economic liberalisation, and the concomitant expansion of the Indian middle-class, to name a few. Less well appreciated is the fact that Rajiv Gandhi also presided over the rise of the most recognisable feature of contemporary Indian politics — the high-decibel, media-driven, professionalised political campaign.

According to some scholars, the 1980s was an era in Indian politics when ‘media politics [was] displacing organisational politics’ and ‘the cassette recorder [was] replacing the local notability and vote banks’ (Rudolph and Rudolph 1987: 150). Such transformations were no doubt the result of the growing ubiquity of televisions, video-cassettes, and Video Home System (VHS) players as items of mass consumption in middle-class households (Boyd, Straubhaar, and Lent 1989; Rajagopal 2001) and the meteoric growth of vernacular language newspapers (Jeffrey2000) witnessed through the decade. Equally so, this is a story of how a small group of political élites and advertising professionals worked behind the scenes to midwife the industry of political marketing in the lead up to the General Elections of 1984.

The Road to 1984

What made the 1980s the pivotal moment for the rise of political marketing? The answer lies in the unexpected confluence of three parallel developments: the growing of the Indian advertising industry and consumer market research; a generational turnover in the Congress party as represented by Rajiv Gandhi and his coterie; and the increased volatility and partisan de-alignment of the Indian voter.

In the early 1980s, the advertising industry in India witnessed spectacular growth. Fuelled by the growing consumer culture of an expanding middle class and proliferating opportunities of advertising in print media and commercial television, Indian advertising firms were raking in an estimated ₹420 crore (ca US$5.2 million today) in annual revenue circa 1981, and there were nearly 400 advertising agencies in the country. However, the primary domain of these advertising agencies was consumer goods, and the field of political marketing was largely non-existent. In the lead up to the 1980 Lok Sabha Election, copywriters at the Bombay-based Rediffusion Pvt. Ltd. made a sales pitch to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on how they could assist the Congress party in designing its election campaign’s communication. Their proposal was turned by Indira Gandhi, but once Rajiv Gandhi arrived on the political scene, these advertising ‘spin-doctors’ found a more receptive audience in the political establishment.

Rajiv’s penchant for technology and computers and his passion for introducing techniques of corporate management in the political domain are well known (Sharma 2022), a sentiment bolstered by the technocratic disposition of his coterie of advisors and close friends, many of whom shared his ideological predilections and technocratic modus operandi. Two prominent names were Arun Nehru and Arun Nanda, both having enjoyed a long stint in the corporate sector before they became Rajiv’s close political confidants. During their time at Reckitt & Coleman and Jensen & Nicholson respectively, Arun Nehru and Arun Singh had developed a close personal camaraderie with Arun Nanda (Managing Director of Rediffusion), who had helped design advertisement campaigns for the products manufactured by the two firms. This professional relationship formed the basis of a close personal camaraderie between the three Aruns, with Arun Nehru in particular playing a key role in facilitating introductions between Rajiv Gandhi and Rediffusion.

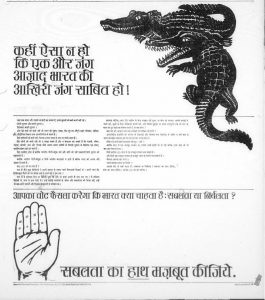

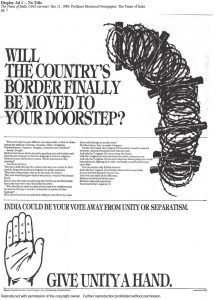

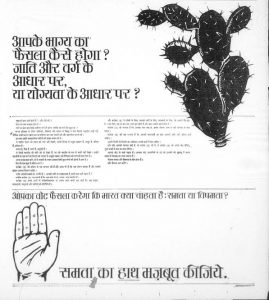

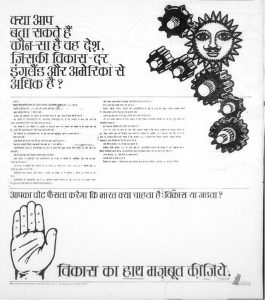

As early as 1982, nearly three years before the Lok Sabha elections that were scheduled for 1985, Rediffusion was brought on board as the key strategist for the Congress party’s election campaign. The intention was to give Rediffusion sufficient time to conduct nationwide surveys, analyse the data, and then develop a comprehensive media strategy for the party. Significantly, what bolstered the influence of advertisement firms on political parties were the strident developments in the field of consumer market research and opinion polling that had taken place in the late 1970s and early 1980s in India, which could now be leveraged to better understand the mood and preferences of the Indian voter. Other firms also assisted the Congress in creating audio-video cassettes and short films, which were screened in moving vans and cinema halls around the country. In total, Rediffusion spent an estimated ₹6-9 crore (US$ ca 737k-1.1 million today) for the Congress campaign (Sharma, unpublished PhD dissertation, 2020). The final product of Rediffusion’s efforts was revealed in the media blitzkrieg that launched in India’s leading newspapers in December 1984. A selection of these campaign posters has been reproduced below:

Source: Left, Navbharat Times, New Delhi edition, 2 December 1984, p. 7; right, Times of India, New Delhi edition, 11 December 1984, p. 5 © For copyright information, please see below.

Source: Navbharat Times, New Delhi edition, 29 December 1984, p. 7 © For copyright information, please see below.

Reading Between the Lines

As a watershed moment for political marketing in India, the Congress campaign posters designed by Rediffusion stand out both in form and content. In form, these posters dwarfed those of the opposition parties not only in sheer size but also in the frequency with which they appeared in English and Hindi periodicals multiple times a week. Thus, for instance, a comparison of the size and format of the campaign adverts of the BJP and the INC from a December 1984 issue of the Navbharat Times (a Hindi-language newspaper) is clearly indicative of the vast chasm in political finance and professional expertise that the two parties had at their disposal. While the Congress advertisement took up nearly three-fourths of the entire broadsheet and was immediately noticeable, the BJP’s advert was relegated to a tiny corner and was barely conspicuous to the casual reader.

Source: Navbharat Times, New Delhi edition, 7 December 1984, p. 7 © For copyright information, please see below.

Source: Navbharat Times, New Delhi edition, 7 December 1984, p. 20 © For copyright information, please see below.

In addition to their format, Rediffusion’s advertisements also gained public notoriety for their communally charged dog whistles, and for stoking the insecurities of the citizens in the aftermath of Indira’s death. Some of the newspaper advertisements designed by the company carried captions such as: ‘Will your groceries list, in the future, include acid bulbs, iron rods, daggers?’, ‘Will the country’s border finally move to your doorstep?’, and ‘Why should you feel uncomfortable riding in a taxi driven by a taxi driver who belongs to another state?’. The imagery of concertina wire, cactii, and crocodiles used to illustrate the posters further amplified the subliminal messages of threat, danger and despair. Against the backdrop of growing secessionist sentiment in different parts of the country (Kashmir, Punjab, Assam) and the assassination of the Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984 by her Sikh personal bodyguards, such political slogans attempted to magnify the sense of insecurity felt by ordinary citizens and portrayed the Congress as the only party that could be trusted to uphold the unity of the nation. The reference to untrustworthy ‘taxi driver(s)’ in the campaign posters was widely understood to be a reference to Sikhs, who were prominent in that trade in cities like Delhi at that time (Singh 2012). At a time when partisan loyalties among the electorate were on the decline, shrill mediatised campaigns like this were an attempt to (re-)build large electoral coalitions around the theme of nationalism, national security, and law and order.

Conclusion

Through the 1990s (and thereafter), the association between advertising firms and political parties gradually became even more commonplace. During each election cycle, a plethora of advertising firms — Clarion, Graphis Ads, Trikaya Grey, Perfect Relations, Madhyam Akshara, Madison, Forefront, Megacorp, Mudra, Nexus, Axis, Jaisons — would vie for the business of political parties with ever increasing budgets. Today, the field of political marketing is populated not just by conventional advertising firms but a plethora of other actors like social media influencers, pollsters, political consulting firms, and ‘Big Data’ experts.

To revisit the roots of the industry of political marketing in India four decades later is intellectually instructive for more than one reason. For one, it shows us how despite enjoying the first-mover advantage over the opposition parties, Congress’s slick media machinery could not keep it invisible at the ballot box indefinitely. Then, as now, political marketing has never been the silver bullet to electoral victory. For another, the 1984 election campaign posters vividly illustrate how thinly veiled communalism and the bogeyman of national security have cast a long shadow on the interface between media and politics in India.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Copyright information: All newspaper clippings have been used by permission of the author under the Creative Commons License/Fair Use policy of LSE blogs.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Rishabh Sharma, 2019, Unsplash.

The ‘India @ 75’ logo is copyrighted by the LSE South Asia Centre, and may not be used by anyone for any purpose. It shows the national flower of India, the Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera [Gaertn.]), framed in a graphic design of waves, and spindles depicting depth of water. The logo has been designed by Oroon Das.