All nation-states have nationalist master-narratives; selective historical memory is crucial to establishing the story. In this post, Dominique Dillabough-Lefebvre takes a tour of the Defence Service Museum in Nay Pyi Taw, and describes its displays — which tell the Burmese military junta‘s official story of the nation through forgetting, remembering and rehabilitating memory.

All nation-states have nationalist master-narratives; selective historical memory is crucial to establishing the story. In this post, Dominique Dillabough-Lefebvre takes a tour of the Defence Service Museum in Nay Pyi Taw, and describes its displays — which tell the Burmese military junta‘s official story of the nation through forgetting, remembering and rehabilitating memory.

As streets across Burma filled with protestors following the military coup on 1 February 2021, lyrics of the song ‘Kabar Makyay Bu’ (lit., ‘We Won’t be Satisfied till the End of the World’) echoed across the country. The song had originated in the country’s anti-junta demonstrations in 1988 in which hundreds if not thousands of unarmed students were massacred on the streets of Yangon by the Burmese Sit-Tat (lit., ‘military’) or Tatmadaw (lit., ‘royal military’, used here interchangeably with the more neutral ‘Sit-Tat’).

For the revolutionaries, this history — written in blood — represents salvation from the fate of a country long shaped by the Sit-Tat, as the youth once again returned to the streets and the jungles to fight the junta.

The evocative echoes of the voices of the street protestors strangely brought back to me a visit I had made a year earlier (2020), to the Defence Service Museum in Nay Pyi Taw, Burma’s purpose-built capital city. The Museum, a 603-acre monument to the State of Myanmar located on the outskirts of the characteristically eery sprawling capital, is a monument to the nation as imagined and projected by the military junta. In doing so, it traces the violent incorporation of the ‘internal enemies’ present on its peripheries, whose very existence is central to most justifications of continued military ‘stewardship’ of the country.

Initially a nationalist, anti-colonial, revolutionary army, the Tatmadaw has never been an ethically- or class-inclusive institution in terms of its beneficiaries. Its persistence as a steward of national ‘integrity’ has, since its inception, been based upon the exclusion and persistent warfare against its perceived ‘others’. The ethnic insurgencies against which the military has waged war are perhaps more readily acknowledged, yet neglected from many narratives are the entire class of landless farmers who constitute the majority of the countries’ population. While this group was not typically the target of military violence, they saw few rewards through half a century and more of military rule, suffering in ways that have been largely ignored in scholarship. While portions of Burma’s Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) have long fought for the end of military rule, the (often landless) Bamar (ethnic Burmese) peasants appear to be at a crossroads in terms of acknowledging the true nature of military suppression. These parallel struggles, often sidelined due to perceived ethnic animosity, illuminate the importance of a national agrarian struggle. Set in relief against the beneficiaries of extended military rule who have been looting the natural resources of the country for decades, these rural farming populations, in cooperation with a younger militant middle class, now have a chance to remember that which the nation itself has learnt to forget.

Reflecting on a quote by the conservative historian Ernest Renan in which he highlights that

‘Forgetfulness, and … even … historical error, [is] essential in the creation of a nation’ (1882/trans. 2018, ch. 9), the political scientist Benedict Anderson replied that ‘the state itself preserved the knowledge which needed to be forgotten for national identity’ (1991: 199f).

*

This post retraces steps through the Museum, marking the slighting of memory which create and mute national histories. A journey through this site of forgetting, it is an attempt to hear the voices ringing across the country differently, refracted through the eyes of a military which portrays the periphery as perhaps its most vital constituting force. I see such an attempt, howsoever partial, as a means to rehabilitate memory — echoing the ‘histor(ies) written in blood’, but also those written in the seemingly mundane daily actions that sustain human life, joy and hope.

Photo 1: (L-R) Portraits of Generals Ne Win, Aung San and Than Shwe in front of different flags © Author (see information below); used with permission.

It is important to highlight what makes this Museum unique: largely empty of visitors, only occasional school tour groups and military personnel visit it. In such a sense, it can be seen as a monument to itself, an empty museum without a nation as witness, in which the military projects its own ideology of conquest and domination. We often approach museums as sites of remembering, but what if we highlight their role in forgetting the past? What can paying attention to such historical exclusions do towards fostering a space in which the younger generations can create meaningful and inclusive futures?

State-building: Violence, Fragile Alliances & Cycles of Revolution

I started writing about this a year prior to the 2021 military coup, having travelled south from Shan State to Loikaw, and then on to Nay Pyi Taw. I passed through Moebye and Pekhon, at the time peaceful settlements not far from the tourist hotspots of Inle Lake. In the aftermath of the coup, these areas have seen tens of thousands of people fleeing due to fighting between the Sit-Tat and newly formed anti-junta groups called Peoples Defence Forces (PDF). The state capital of Loikaw was hit by junta airstrikes in January 2021, causing nearly half of the population to desert the city.

I returned to photographs I took during my visit to the museum as a means to explore the bewildering slippages between indifference, trauma, violence and processes of forgetting, now ever more present amidst renewed armed conflict in the lowlands of the country. While fighting has continued since independence, many EAOs involved in these long-standing armed struggles were often considered — both by significant portions of international community and many Bamar alike — as peripheral to Myanmar’s future. They were often cast as groups that would be defeated by a stronger Burmese force or wither away in the face of financial incentives. Perhaps more significantly, the international community and much of the country’s population seemed to be largely unaware of the ongoing realities of these insurgencies, for example often saying that groups reporting human rights abuses were exaggerating the scale of conflict in the borderlands.

Yet, in ways far more significant than after the uprisings of 1988, the EAOs have become a central element in a coalition of forces aiming to overthrow the junta. Several of them, in fact, never stopped fighting since the 1950s (not long after independence) in what is often called the world’s longest ongoing civil war. How these ongoing conflicts were largely ignored as then US President Obama welcomed a semblance of democracy to Myanmar, or as urban Bamars in most parts of the country forgot about their EOA allies from the anti-juntademonstrations of 1988 is a critical piece of this puzzle of forgetfulness and indifference. As large groups of youth flee once again to the jungles to train with these established EAOs — as in 1988, but in far greater numbers — questioning the erasures contributing to such outcomes seems essential to Myanmar’s future.

Through promoting acts of forgetting the ‘others’ who have shaped present-day Burma, whether through exclusion or incorporation, the military have long managed to monopolise a narrative of an ethnic (Bamar) and religious (Buddhist) nation. In the aftermath of the coup in 2021, such a national identity is being challenged at a scale unseen since the years of civil war following independence.

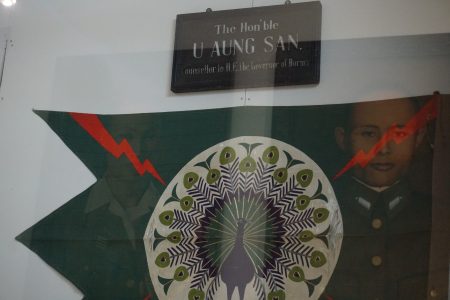

The Tatmadaw has been the most powerful institution in Burma since independence from British rule in 1948. It traces its origins to the anti-colonial revolutionary forces of the Burma Independence Army, perhaps most famously symbolised through the figure of Aung San, portrayed as the father of the Burmese nation. The Sit-Tat’s self-declared raison d’être has been to purge the country of ‘internal enemies’ to protect national sovereignty, and thus to prevent the disintegration of the union.

Photo 2: Reflection of portrait of Aung San in a display of the flag of the Burma Independence Army © Author (see information below); used with permission.

There has been limited, and at best partial, access to the Myanmar military and its archives for researchers (see Callahan 2003, Myoe 2009, Nakanishi 2013; Callahan acknowledged that her archival research, considered by many to be one of the most authoritative accounts of Tatmadaw history, is ‘at best a tentative attempt to understand the internal dynamics of a military’.). Accounts of the Tatmadaw written by Burmese authors, on the other hand, tend to focus on specific military battles rather than providing in-depth details on its inner workings. Such partial access has often led to portrayals of the Sit-Tat and its leaders as irrational, mystical and uniquely psychopathic. Despite its bold slogans such as those framing Nick Dunlop’s iconic ‘Brave New Burma’ — ‘Move, Shoot, Communicate’ and ‘Our Native Land is Fire and Manoeuvre’ — to paint a picture of a military ideology as part of some uniquely Burmese psyche fails to see the parallels between military institutions and forms of colonialist ethno-nationalism worldwide. I discuss this point in greater detail elsewhere, touching on the role of imperial museums worldwide as sites of ‘continued violence’, as recently described in Dan Hicks’ stellar The Brutish Museums.

*

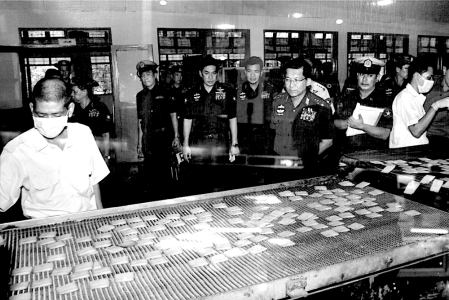

What the Museum in Nay Pyi Taw offers is a meticulous documentation of the conflicts against its internal enemies, ranging from panoramic oil paintings of notable battles to lit-up miniature models of porters and mules re-supplying military bases in mountainous regions. Such striking displays lie next to missiles filed neatly in glass cabinets; in other rooms there are more banal photograph displays of junta leader Min Aung Hlaing visiting military biscuit and football factories.

Photo 3: General Min Aung Hlaing visiting a confectionery production factory © Author (see information below); used with permission.

But beyond this, the displays trace the genealogy of the state as imagined by the military itself, one marked by endless strife. In marking such conflicts, the Sit-Tat highlight acts of violence by which it consolidated state power, yet ‘forgets’ the importance of the fragile alliances between many of the same armed actors with whom the military has been in ongoing conflict. Here I refer to the range of economic and military alliances that have shifted over time between the Tatmadaw, its officials and associated cronies and the armed groups typically seen as its enemies. While this could be seen as part of a divide and rule strategy (such as concessions or the incorporation groups) I argue that they must be seen as part of the very fabric of the state itself. Notable examples include the incorporation of EAOs as nationally subordinate Border Guard forces, or the Sit-Tat’s temporary tactical alliance with the United Wa State Army to oust Khun Sa’s Mong Tai Army out of southern Shan State. As new alliances emerge between groups of the Bamar agrarian class and typically ethnically-aligned EAOs, addressing these silences can help move towards a new form of historical reckoning.

Photo 4: Diorama display of Military Work against Insurgency © Author (see information below); used with permission.

Photo 5: ‘Without Communication You Can’t Command & Control’; Museum Guard in Military Uniform posing in front of display of Signals Intelligence © Author (see information below); used with permission.

Photo 6: Sculpture of a soldier feeding a child © Author (see information below); used with permission.

Photo 7: The author viewing a display of rifles at the Museum © Author (see information below); used with permission.

Looking through the museum, its displays of military iconography, nationalist histories and extensive collections of weaponry are emblematic of the exclusions of the state. Addressing such historical silences through the Museum might help towards a reconciliation would that would address the dynamics of shifting alliances and conflicts, at a moment when the boundaries between those cast as state and non-state actors becomes ever more unclear. Studying how the nation has been taught to forget, in other words, is essential to how it can remember a new past and move forwards. The Defence Service Museum in Nay Pyi Taw offers us meaningful landmarks towards such a goal.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and not of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photographs © Personal collection of Dominique Dillabough-Lefebvre; no photograph may be used/reproduced without written permission of the author.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Dominique Dillabough-Lefebvre, Defence Service Museum, Naypyidaw, Myanmar, 2020. ‘Statue of three soldiers. One holds aloft a leafy branch, another raises a five-pointed star, and the one in the middle carries an unfurled flag. The statue’s massive red and white pedestal surmounts a large white star, above the emblem of Burma’s armed forces (Tatmadaw). Reminiscent of another 10-metre high statue of Burma’s three warrior kings (Anawratha, Bayinnaung and Alaungpaya) which tower over the main parade ground of Naypyidaw’: description from Andrew Selth, ‘A Statue in Naypyidaw‘, 2012.

The ‘Myanmar @ 75’ logo is copyrighted by the LSE South Asia Centre, and may not be used by anyone for any purpose. It shows the national flower of Myanmar, Padauk (Pterocarpus macrocarpus), framed in a design adapted from Burmese ikat textile weaves. The logo has been designed by Oroon Das.

*