High-rise living is increasingly common in urban areas, especially in fast-growing economies like India. Even as residential living grows vertically, reaching skyward, Ishita Patil discusses how these gated spaces reproduce socio-cultural practices and prejudices even as they promise exclusive, modern communities of living.

In ‘India’s New Middle Class’, Leela Fernandes studies the rising middle class in India, their internal differences and political practices. This group, which emerges through India’s efforts at economic liberalisation, marks its distinction via representational and classificatory practices, by adopting certain lifestyles, cultures and consumerisms.

By converting forms of capital available to them, the middle class tries to preserve their social standing and develop capacities for upward mobility, shaped largely by an individual’s position in the existing structure of the society. Middle-class culture also plays out in the public sphere, and politics, through the exercise of power on the reclamation of public space (like the removal of street hawkers), described by Amita Baviskar as ‘environmental bourgeoise’.

The rise of this new class saw a parallel rise in the advertising industry, and efforts by private/corporate companies to sell their products to them. Through visual representation, modern technology assured the middle-class of a non-erasure of their traditional values: an advertisement campaign by ‘Carrier’ (an brand of airconditioners) shows a sadhu (mendicant) sleeping comfortably in an air-conditioned room. The choice of a sadhu for the advertisement rides on the notion of preserving traditions with modernity. In this post, I discuss the role of advertisement as a means of creating aspirations, lifestyle changes, the politics of visibility associated with it, and the paradoxical nature of upward mobility.

*

The stability of owning a house is a milestone in an individual’s life, and the importance it plays in society, and political spaces, cannot be stressed enough. Real estate is a booming market marred by the politics of inequality and the value attached to it is reflected in the prices attached to it. The significance of housing is also visible in the growth of real estate developers, and their advertisements all over the city. The images in this post are from two cities – Mumbai and Bengaluru; the common theme across them is the provision of premium, luxurious, world-class amenities by the property developers.

As described by Falzon, these gated communities offer a degree of ‘inward-orientation’ by selling the idea of having a city-within-the-city with amenities like parks, swimming pool, gyms, activity centres, etc. The central notion of the gated community is to have a space unencumbered by the chaos of outside society. Fear of crime and the need for security due to rising communal tensions, over-population and unstable economic conditions play a crucial role in the demand for gated communities.

Forces of urbanisation and modernisation are to gradually break down caste-based segregation and discrimination in Indian cities. But rather than being ‘melting pots’ and places of social mobility, cities are increasingly mirroring social and economic inequalities of villages. Indian cities are highly segregated along lines of caste and religion.

Caste is a crucial feature of social hierarchy in India that has adapted itself in the urban context through the built environment, and hides in plain sight in the city. Residential segregation by caste is widespread and more-pronounced than segregation based on socio-economic status, and that is not all: not only are metro cities segregated as a whole, they are also highly caste and religion-segregated at the neighbourhood level. But as is visible from the images below, this segregation is now reproducing itself within gated communities, and even within the household.

*

Notices specifying separate elevators for ‘maids, servants, cooks, delivery boys, courier boys, guards, etc’ are a common sight in many new residential complexes. Apartment blocs with only one elevator often impose rules that restrict service personnel from using it simultaneously with residents. But this does not end here. Nowadays, it has become increasingly common for apartments to feature a small, non-ventilated room with an attached, tiny washroom, as a ‘servant’s quarter’. These quarters are typically designated for families employing a permanent, stay-at-home domestic help. Notably, these ‘quarters’ have a separate entry/exit door, strategically designed to keep the domestic worker out of sight, perpetuating a sense of segregation.

In essence, the social norms prevailing among the middle class have profoundly shaped and altered the physical landscape, solidifying practices that reinforce unequal treatment within residential spaces.

*

The language of advertisements, like ‘Own a Possession as Precious as the Queen’s Crown’ and others showcase the creation of a demand for housing, but with a distinctive lifestyle. The epitome of this distinctive aspiration is the visual representation of a project called ‘Passcode Uncommon’. Their advertisements have a common theme, an image divided in two: a black-and-white image of a slum, paralleled with an image of a happy and posh lifestyle (see Photo 1). These advertisements go with the tagline of ‘Live Uncommon’. Clearly, the Indian middle class has travelled from its famous cartoonist & illustrator R.K. Laxman’s ‘Common Man’ to the desire for an ‘uncommon, lifestyle.

Photo 1: Screen-grab of ‘Passcode Uncommon’, Vihang Group of Companies, Mumbai, 2023 © For copyright information, see below.

In a recent article Pankaj and Jha discuss the struggles and challenges of the Dalit middle class in establishing their position in society. Here, again, the culture of developing and adopting distinguishing lifestyles, and consumption practices, play an important role in achieving the status of being middle class. Further, the Dalit middle class is also cautious of their residential location, as they identity the city as a space for lower classes and those belonging to the élites. This perpetuates segregation within the city, but also brings out another aspect cutting across caste- and religion-based segregation, one that is based on distinctive and classificatory practices.

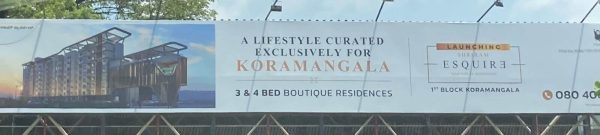

An advertisement in Mumbai for a ‘50-storeyed Award-winning Skyscraper’ promises its potential buyers that ‘even your views start at a higher level than others’ (see Photo 2). This advertisement (and several others) offer ‘The ultimate abode of Urban Luxury’ promising a ‘A Lifestyle Curated just for You’ in a way where the idea of exclusive, secluded housing is normalised and made attractive (see Photos 3 and 4). Further, as the boundaries of the new middle class are determined by their everyday practices, the subordinate fraction of the middle class aspires to attain and emulate the practices of the dominant fraction of the middle class, eventually reproducing the inequality and discrimination inherent in their cultural practices.

Photo 2: Street hoarding of ‘Higher Views’, Kalpataru Group, Mumbai, 2023 © For copyright information, see below.

Photo 3: Street hoarding of ‘Curated Lifestyles’, Shriram Properties, Bengaluru, 2023 © For copyright information, see below.

Photo 4: Street hoarding of ‘Ultimate Abode’, Naman Habitat, Mumbai, 2023 © For copyright information, see below.

*

Not only are cities highly segregated but now this exclusion has also seeped into household units. Housing has become a space for capitalist production as political intermediaries have enabled their growth and sustenance over time. Built on capitalist and élite ideas, gated communities embody exclusionary notions and harbour spaces of discrimination. This has effects on interpersonal relationships between individuals living within these gated communities, necessitating the need to study housing as a space of class and caste inequality. Advertisements create aspirations which rely on exclusionary, secluded, and private living. For lower caste communities, for whom it was vouched that the urban would be a haven devoid of caste discrimination and segregation, the city has not only accommodated caste discrimination but worse, normalised it under the veneer of ‘luxurious’ world-class living. Here, it is not just the language that is promoting this idea of social exclusion but also the conception and use of space in terms of the floor plans, service elevators, and so on.

Indians now are increasingly living in cities where exclusion has become a normalised and well-accepted bearing of urban living.

*

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Copyright information © All advertisements are the property of the respective companies. All photographs reproduced here have been taken by the author. Photo 1 is a screen-grab from the Facebook page of Vihang Group of Companies; photos 2-4 are from street hoardings, and used here by permission of the author under the Creative Commons License/Fair Use policy of LSE blogs.

Banner image © Vamshi, Bengaluru, 2022, Unsplash.

*

This is an important topic. It could have included the EWS mandatory houses. During corona the maids helped many seniors survive but post COVID the lifts are segregated again.

Very thought provoking!

Lifts are segregated for ease. Not due to caste segregation lol. Indian cities are not segregated on caste lines. Nobody in city cares who comes from which caste. Segregation is on economic factor which can be seen. This article is funny and the author tries hard to find caste everywhere including servant quarters. If servants will not be in servant quarters then where they will be? In bedroom?