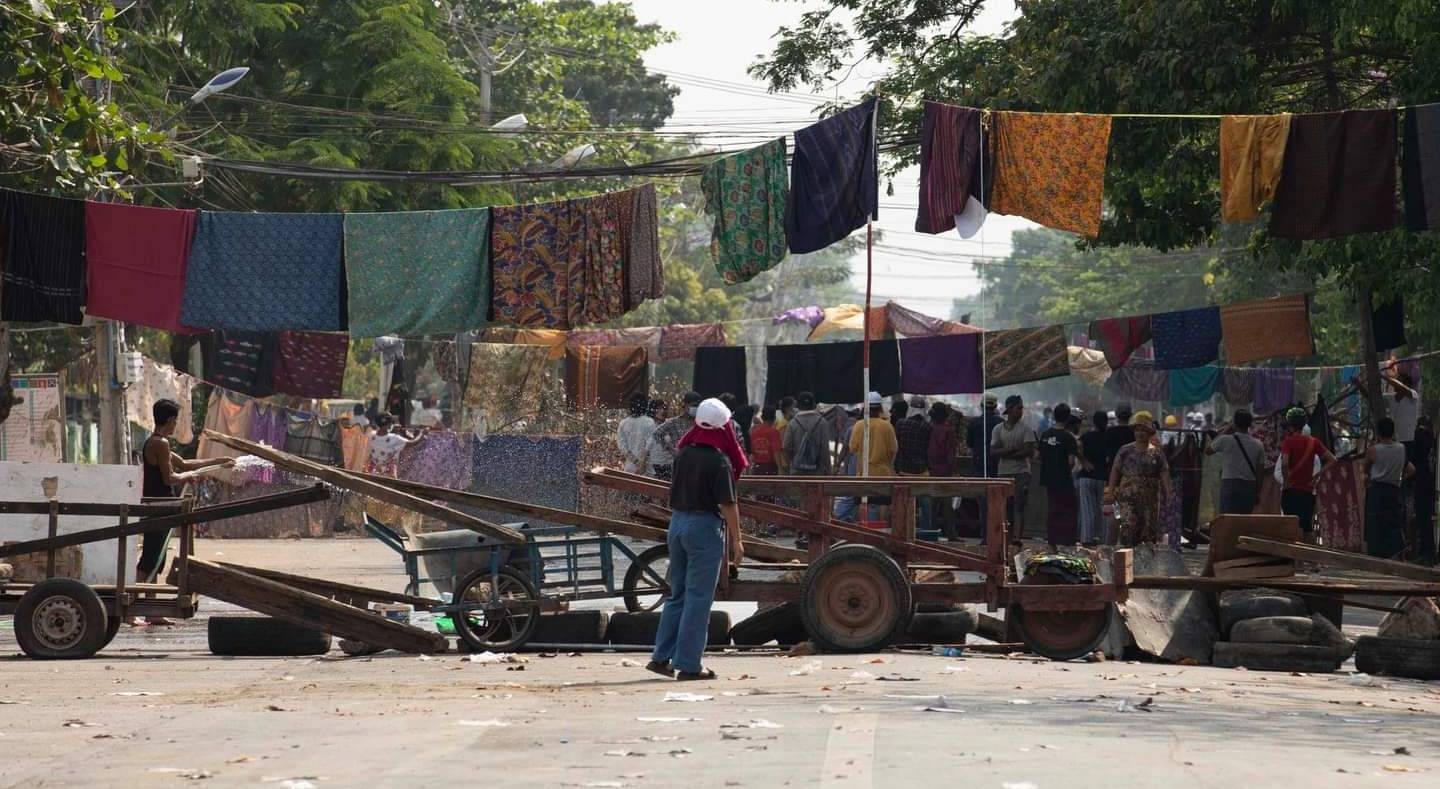

On show in the Atrium Gallery at LSE, ‘Not Another Protest Exhibition: Myanmar in Revolt & Feminist Art Practice’ features the work of Chuu Wai, a multidisciplinary artist from Shan State, Myanmar, now living in Paris. In this post, curator and LSE PhD Research Scholar Sara Wong discusses the historical and socio-political context of contemporary Myanmar through artwork that responds creatively to the historic role that women have played in resisting military rule. (See also ‘“Htamain” at the Front: Breaking Tradition, Resisting the Coup in Myanmar‘, published today.)

In this post, I reflect on Chuu Wai’s creative practice, and its relation to feminist and revolutionary imperatives. In doing so, I hope to open up broader questions about the co-constitutive relationship between art, politics and resistance in post-colonial contexts.

Revolution and the Everyday

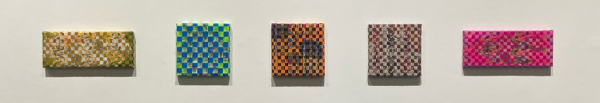

In creating artworks for this exhibition, Chuu Wai uses materials relating to everyday objects and practices: from fabric and textiles to woven baskets and photographs. Ubiquity is an intentional aesthetic motif in the pieces, attended to primarily through the deployment of a familiar basket-weaving technique from baskets that are used in everyday, mundane ways in Myanmar. Using this as the canvas, Chuu Wai interweaves collaged elements, paintings and fabric in the Woven series (Image 1). In doing so, the artworks ask: how might we understand the relationship between the everyday and the revolutionary? This open question, of which both the artworks and exhibition obscure obvious answers, is especially important in a political context where, over three years on since the military coup in February 2021, people across Myanmar are subject to authoritarian rule and experiences of abject violence on a daily basis. Says Chuu Wai,

I simply ask the questions in the paintings, and I hope people will ask their own questions through the paintings as well.

The visual impact of utilising this technique results in a jarring viewing experience, one where you do not quite know where to look or what you are looking at. This is intentional for the artist, who views her artwork as a kind of ‘puzzle’ or ‘game’ to be pieced together and worked through by the audience.

Image 1: ‘Woven’ series: Two 20x50x3.5cms, three 20x20x3.5cms, acrylic and collage on canvas, woven with Myanmar textiles, 2024 © Chuu Wai. Used with permission; see below for more details.

Textiles and Representation

Textiles are another important thread which runs through the pieces in this show. In some paintings, the artist makes use of fabric as a canvas, in others it is interwoven with other collaged and painted elements (Image 2). The use of fabric appropriates a cultural stigma which sees women’s skirts (htamain) as unlucky, dirty and a thing to be avoided by men. This very stigma acted as inspiration for protestors in Myanmar immediately after the 2021 coup, who used the widespread idea that htamain should not be walked under, and hung them across the city in order to barricade military and police personnel. Although the artist’s use of fabric preceded this strategic use in the protest movement, the artworks also commemorate this approach and, in doing so, record this creative protest practice in the wider historical archive. Representing the conflict in this way was important to the artist:

I wanted to do a bit of reflection on war and conflict without saying it directly, because a lot of artists who were displaced from Myanmar, when they arrived in Europe, many galleries and people expected more violent work, for us to describe killings and conflicts. I wanted to approach it in a different way.

This illustrates the ways in which representations of political violence, resistance and conflict are shaped not only by individual artists’ renderings but also by a broader cultural (and political) infrastructure subject to processes of tokenisation and exploitation, one which reflects and reproduces wider global inequalities.

Image 2: ‘Chew you up or Spit you out’, 120x90cms, acrylic and collage on Myanmar textile, 2024 © Chuu Wai. Used with permission; see below for more details.

The use of fabric and textiles — each with their unique patterns, dyes and materials — in the artworks also speaks to the ethnic diversity found across Myanmar, where hundreds of languages are spoken amongst its many ethnic communities. Since its demarcation as a nation-state in 1948 following independence from British colonial rule, Myanmar has always been a multi-ethnic country, despite the Bamar (the dominant ethnic community) historically holding most positions of power in the military and government. It is important to note that while the 2021 military coup (and resistance to it) was an important historical juncture, non-Bamar ethnic communities (like the Rohingya) continued to experience violence and genocidal actions of the Myanmar military even through the decade of ‘democratic transition’ (2011–21) that preceded it.

Collage and Photographs

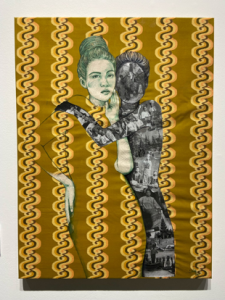

Throughout the pieces featured in this exhibition, the artist uses archival photographs that both reflect and destabilise the notion of an enshrined historical past where women in Myanmar (then Burma) dressed and presented themselves ‘modestly’. Taken from archival sources, newspapers and collections, these photographs are overlaid with painted figures of women embodying postures and wearing clothing which subvert this ‘modesty’ (Image 3). In this way, the artworks aim to disrupt and re-write cultural codes which the artist sees as confining women to imagined histories of modesty and diffidence. A number of photographs used are taken from the last dynastic period in Burma (Konbaung Dynasty, 1782–1885) before British colonisation led to the abolition of the monarchy. Chuu Wai reflected on her choice of using archival photographs from this era, saying,

When people criticise women, how they should or how they shouldn’t dress, they take this era and this time as the representation of tradition. And then when we look at the real portraits of these, it was a little bit different. They look modern and they look free.

The juxtaposing of mixed media and collage like this leverages the artworks’ broader historical questions about the relationship between perceptions of the past, the politics of the present and possibilities for the future.

Image 3: ‘Shadows in the Ayeyarwaddy’, 120x90cms, acrylic and collage on canvas, 2024 © Chuu Wai. Used with permission; see below for more details.

Protest and Displacement

The pieces featured in ‘Not Another Protest Exhibition’ also interweave words taken directly from posters from protests during the height of the Civil Disobedience Movement. Written demands from protesters interwoven into these pieces range from basic things like, ‘I want to live and sleep peacefully’, to hopes around livelihoods, ‘I don’t want to go back to riding a trishaw for a living after high school’, to, finally, a reflection on displacement from the artist herself which reads, ‘I’m just the one who doesn’t know where home is’.

According to the UNHCR, nearly 2 million people are internally displaced in Myanmar, and 1.3 million are refugees or seeking asylum outside. While exile and displacement are not the primary focus of Image 4, this subtle reference helps humanise the rippling impacts of military rule, as a way to relate to these unfathomable statistics differently. Many artists from Myanmar, including Chuu Wai, participated in the 2021 protests and as a result had to flee the country; they now continue their (creative) resistance from elsewhere. In trying to articulate the emotional experience of displacement, Chuu Wai says,

I feel more and more dissolved in this place, you know?

Picking up where the limits of words leave off, her artwork has allowed her to reflect on the embodied and intangible experiences of displacement.

Image 4: ‘Want To Sleep Peacefully’, 20x20cms, acrylic and collage on canvas, woven with Myanmar textile on textile canvas, 2024 © Chuu Wai. Used with permission; see below for further details.

*

By linking feminist imperatives with revolutionary ones, the artworks in this exhibition draw connections between patriarchal oppression and military rule, and in doing so, allow audiences the opportunity to engage with such linkages not just intellectually, but also affectively. From paintings and poetry to music and performance, (feminist) resistance in Myanmar and the diaspora to colonial, military and authoritarian rule has often been brought to life in varied and creative ways. This exhibition is but one expression of the ways in which art and revolutionary politics do (and could) overlap.

*

Not Another Protest Exhibition: Myanmar in Revolt & Feminist Art Practice (29 January–23 February 2024), Atrium Gallery, OLD Building, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE, is open to the public on weekdays, 9am–5pm.

Copyright information: All artworks © Chuu Wai; all photographs © Sara Wong. Used with permission; no artwork image/photograph may be used by anyone without prior written permission of the artist and photographer.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent the views of the ‘South Asia @ LSE’ blog, the LSE South Asia Centre or the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please click here for our Comments Policy.

This blogpost may not be reposted by anyone without prior written consent of LSE South Asia Centre; please e-mail southasia@lse.ac.uk for permission.

Banner image © Sara Wong, ‘Not Another Protest Exhibition: Myanmar in Revolt & Feminist Art Practice’, 2024. Used with permission.

*