I listened to a lecture called “Empirical Economics and Causality” by LSE Professor Jorn Pischke, who talked about the role of econometrics. Undergraduate students will know Pischke for his popular econometrics course at the LSE and graduate students will be familiar with his book, “Mostly Harmless Econometrics”.

Econometrics is a class—in fact—the class where students are tested (no pun intended) on whether they can consummate their knowledge of statistics, calculus, and linear algebra with their understanding of microeconomics and macroeconomics to form meaningful and testable empirical questions. Because of its prerequisites, the econometrics is usually offered as one of the last classes that economics majors can take. For many students, it is a defining moment when they can see that economics isn’t just about modeling but is in fact a social science—with an emphasis on science.

Econometrics is a class—in fact—the class where students are tested (no pun intended) on whether they can consummate their knowledge of statistics, calculus, and linear algebra with their understanding of microeconomics and macroeconomics to form meaningful and testable empirical questions. Because of its prerequisites, the econometrics is usually offered as one of the last classes that economics majors can take. For many students, it is a defining moment when they can see that economics isn’t just about modeling but is in fact a social science—with an emphasis on science.

The governing question of his talk was: “can empirical economics answer causal questions?” The answer, according to Pischke, is yes.

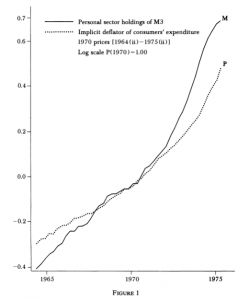

As any first-year statistics course would tell you, a big problem about understanding data is the correlation does not imply causation (which even leading newspapers will get wrong). That this claim is crap has been most humorously noted in Sir David Hendry’s inaugural lecture at Oxford, where he notes a correlation coefficient of over 0.99 between annual inflation and cumulative occurrences of dysentery in Scotland. (for more on Hendry’s example, read his article “Econometrics-Alchemy or Science?” (Economica, 1980).

Pischke chose to illustrate this with a more intuitive example by showing a scatterplot of deaths by drowning on ice cream production—and sure enough, there seemed to be a positive correlation between the two. Could it be that there was some toxic substance in ice cream that made children more prone to drowning? Intuitively, the answer here is no; one would assume that ice cream has little effect on children’s ability to stay afloat.

Econometrics takes these questions seriously and takes a methodical approach to answering them. Here, we could use a RCT (randomized control trial) to see if there really is a causal relationship between ice cream consumption and susceptibility to drowning (another method used in determining causal relationships is instrumental variables, which we defer to a later blog post). We can randomly pick half of the children and bar them from eating ice cream. If we find that they are just as likely to drown as those who did eat ice cream, then we can do away with the claim that ice cream causes children to drown.

This approach has been especially popularized in the development economics literature, thanks in no small part to the work being done by Esther Duflo (read her book, Poor Economics, for a nontechnical introduction to some of her work done in poor countries). But Professor Pischke cautions that there are criticisms of the experimental approach that we ought to take into account. One is an issue of question drift, where Raj Chetty states:

“People think about the question less than the method. They’re not thinking, ‘What important question should I answer?’ So you get weird papers, like sanitization facilities in North American reservations.

While an experimental approach to economics may yield valuable answers, it is important to make sure that we are not just looking at “small potatoes” but rather big questions about economics.

Another issue is the problem of external validity. A paper by Carpenter & Dobkin (2009) shows that motor vehicle fatalities in the US jumps at age 21, which they attribute to the legal drinking age. But as far as policymakers are concerned, the data won’t tell us anything about whether or not banning alcohol will do anything to raise or lower the mortality rate.

While econometrics offers us valuable methods in shedding light on the causal relationship between variables, the task is often much easier said than done.

All the more reason for you to join in on the academic inquiries of our day.

//By Ryo TAKAHASHI, LSE.