For many years, political science research has suggested that women know less about politics and government than men do. In new research, Melissa K. Miller finds that how we ask people about their political knowledge is biased to favor men. If we remove ‘don’t know’ options from multi-choice political surveys and expand questions to include government programs and state politics, she writes, it turns out that women know just as much as men do about politics, if not more.

For many years, political science research has suggested that women know less about politics and government than men do. In new research, Melissa K. Miller finds that how we ask people about their political knowledge is biased to favor men. If we remove ‘don’t know’ options from multi-choice political surveys and expand questions to include government programs and state politics, she writes, it turns out that women know just as much as men do about politics, if not more.

In the aftermath of the historic 2018 midterm elections, with a record number (131) of women elected to Congress, it is hard to believe that the conventional wisdom has long held that women know less about politics and government than men. Yet this is what decades of political science research suggests.

For years, political scientists measured political knowledge in ways that boosted men’s scores on quiz-style survey questions while depressing women’s. Two major flaws in the measurement of political knowledge led to an apparent gender gap and the impression that women knew less than men.

The first flaw was the seemingly innocuous availability of a “don’t know” option when respondents were asked standard survey questions like “Which party has the most members in the US Senate?” and “Which party is more conservative at the national level?” It turns out that women tend to be less likely to guess than men. Right out of the box, this puts women at a scoring disadvantage when correct answers to multiple-choice-style questions are tallied.

Imagine two survey respondents; let’s call them “Freddy” and “Frieda.” Each has exactly the same amount of (partial) knowledge relevant to the question, “How much of a majority is required for the US House and Senate to override a presidential veto?” Neither Freddy nor Frieda is 100 percent certain of the majority required, but both think to themselves, “It’s definitely more than a simple majority.”

Educational testing research suggests that Frieda will be less confident than Freddy. As such, Frieda is more likely to choose the “don’t know” option than Freddy. Frieda thus automatically earns a “0” toward her aggregate political knowledge score. As a more confident guesser, Freddy automatically earns a higher score than Frieda on any set of knowledge questions – even if his actual political knowledge is exactly the same as Frieda’s.

To make matters worse, respondents were traditionally surveyed either over the telephone or face-to-face, with the interviewer reading the following standard script at the outset: “Many people don’t know the answers to these questions, so if there are some you don’t know, just tell me and we’ll go on.”

Guess who was more likely to take the bait offered in the introductory script? Not just our fictional Frieda, but women in general.

A second measurement flaw contributing to the apparent gender gap in political knowledge was the definition of political knowledge itself. Think for a moment about how you would measure political knowledge if you only had a single survey question to do it. What question would you pose? How about if you were allowed a handful of questions to measure political knowledge? What should those questions be? These are difficult considerations precisely because there is no single agreed-upon definition of what constitutes politics.

In the 1990s political scientists gravitated toward a standard set of five survey questions to measure political knowledge. Each pertained to national-level political figures (e.g. “What job or political office is currently held by Al Gore?”) or the rules of the game at the national level (e.g. “Whose responsibility is it to determine if a law is constitutional or not?”).

Photo by Alexis Brown on Unsplash

Notice how these standard questions pertain only to national politics, where men have traditionally dominated the most. Even after the 2018 midterms, women occupy less than one-quarter of the seats in the US Congress.

Measuring political knowledge using survey questions about national-level politics and political figures disadvantages women. Would men be similarly disadvantaged if forced to demonstrate their knowledge of a political system dominated by women? Of course. Recent research in states with at least one woman serving as US Senator found that women in those states were significantly more likely to be able to name her than men.

Measuring political knowledge using questions narrowly focused on national-level politics and the rules of the game is additionally problematic since it ignores knowledge of what government does in favor of who occupies national government positions and what rules govern relations between its branches. A powerful argument can be made that knowledge of government programs is vitally important in a democracy.

Researchers in both the US and Canada have found women’s knowledge to be the same as or even surpass men’s when survey respondents are queried about local government as well as specific government programs.

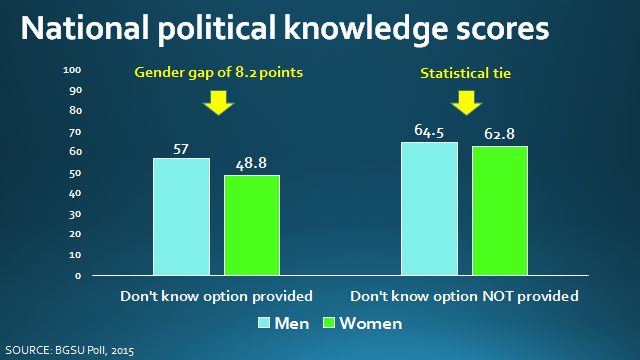

So what becomes of the gender gap in political knowledge when both of these design flaws are simultaneously corrected? Data from the BGSU Poll – a statewide, web-based survey of 804 Ohio voters in 2015 – reveals that the gender gap vanishes or, in some cases, even reverses.

Respondents to the BGSU Poll were queried about their knowledge of politics and government with multiple choice survey questions in three different domains: 1) national-level politics and the rules of the game; 2) state-level politics; and 3) government programs. In addition, the sample of voters was randomly split in half. Half were shown a don’t know option along with three multiple choice options; the other half were not.

Women scored significantly lower than men only when given a don’t know option and asked about national-level politics and the rules of the game. Sure enough, as Figure 1 shows, there was a significant gender gap of 8.2 points. But amongst those randomly-selected respondents who were not provided a don’t know option, women’s and men’s scores were statistically indistinguishable. The gender gap vanished.

Figure 1

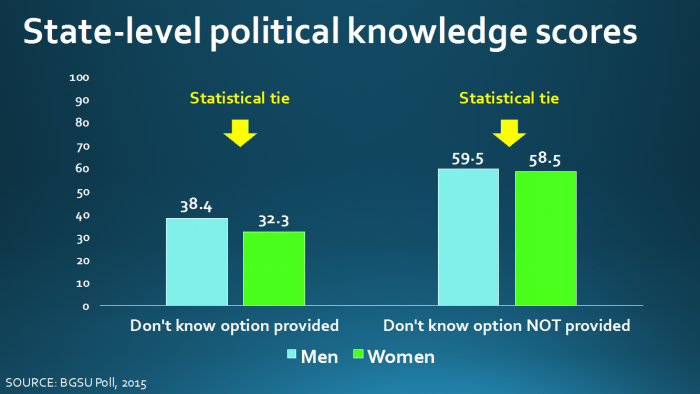

When the definition of politics shifted from the national to the state level (Figure 2), there was no statistical difference in scores between women and men. The availability of the don’t know option did not make a difference. Either way, the gender gap was non-existent.

Figure 2

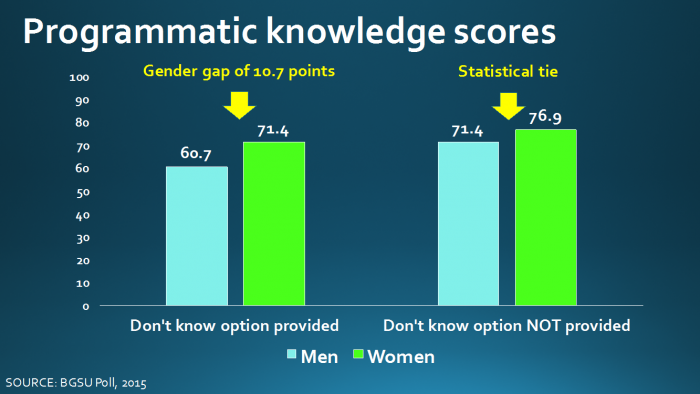

When the focus shifted to knowledge of government programs (Figure 3), a gender gap emerged, but only when the don’t know option was available to respondents. Strikingly, the gender gap favored women, who scored nearly 11 points higher on average than men. Amongst those respondents to whom a don’t know option was not available, women’s and men’s scores were again statistically indistinguishable. And incidentally, each of these findings withstood statistical controls for age, education, race, income, and partisanship.

Figure 3

Savvy readers will notice from the figures accompanying this article that scores increased among both women and men when the don’t know option was omitted, regardless of knowledge domain. This begs the question: is it appropriate to measure political knowledge knowing that scores will be inflated by forced guessing?

Partially inflated scores seem a small price to pay for a clean measure that doesn’t conflate political knowledge with the propensity to guess. Especially when the goal is to compare knowledge across subgroups of the population, omitting the don’t know option is the only way to create a level playing field.

Broadening the conceptualization of political knowledge beyond the national level also makes sense. Citizen interaction with government may be both more commonplace and more desirable at the local and state level. Government programs and services are often delivered at these lower levels of government. Surely there is value in citizen knowledge of both lower levels of government and programs and services offered by government.

In short, it is time to dispel the myth that women are less politically knowledgeable than men. Women know more than you think.

- This article is based on the paper ‘Who Knows More About Politics? A Dual Explanation for the Gender Gap’ in American Politics Research

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2J9LzZU

About the author

Melissa K. Miller – Bowling Green State University

Melissa K. Miller – Bowling Green State University

Melissa K. Miller is an associate professor of Political Science at Bowling Green State University. Her research focuses on gender and politics, voter behavior, and political participation. Her work appears in Public Opinion Quarterly, Political Research Quarterly, Politics & Gender, and PS: Political Science & Politics, among others.