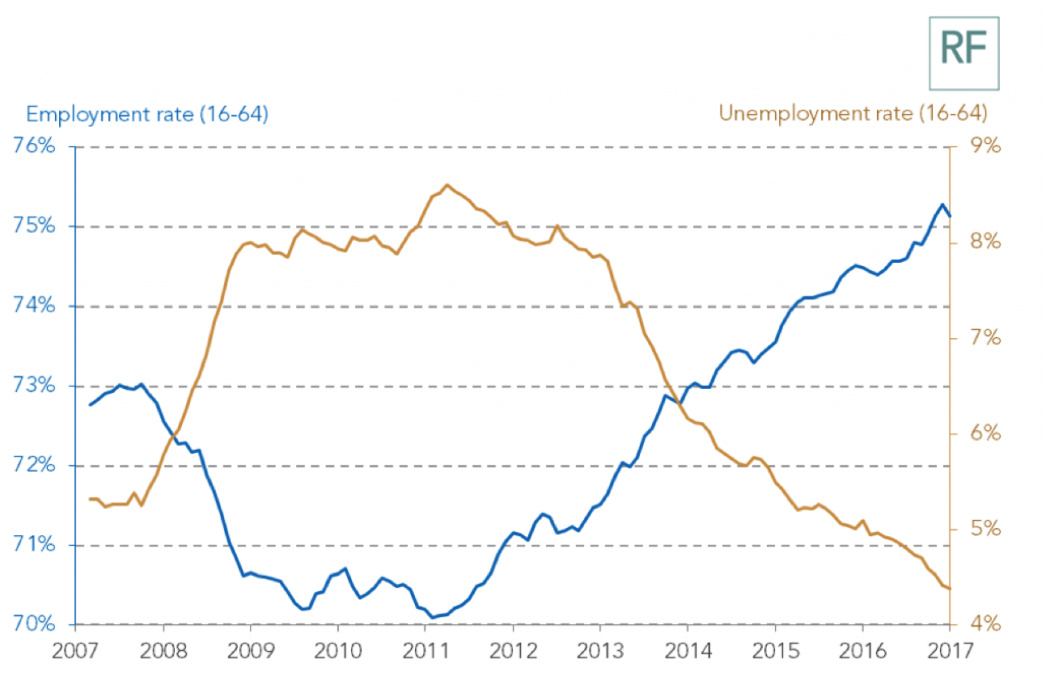

Employment is at a 40-year high, while pay is stagnating. That, in brief, sums up the last few years of changes in Britain’s labour market. As Figure 1 shows, politicians rightly highlight that employment and unemployment are undeniably trending in the right direction.

Figure 1. UK employment and unemployment rates (all aged 16-64)

Source: Resolution Foundation analysis, ONS

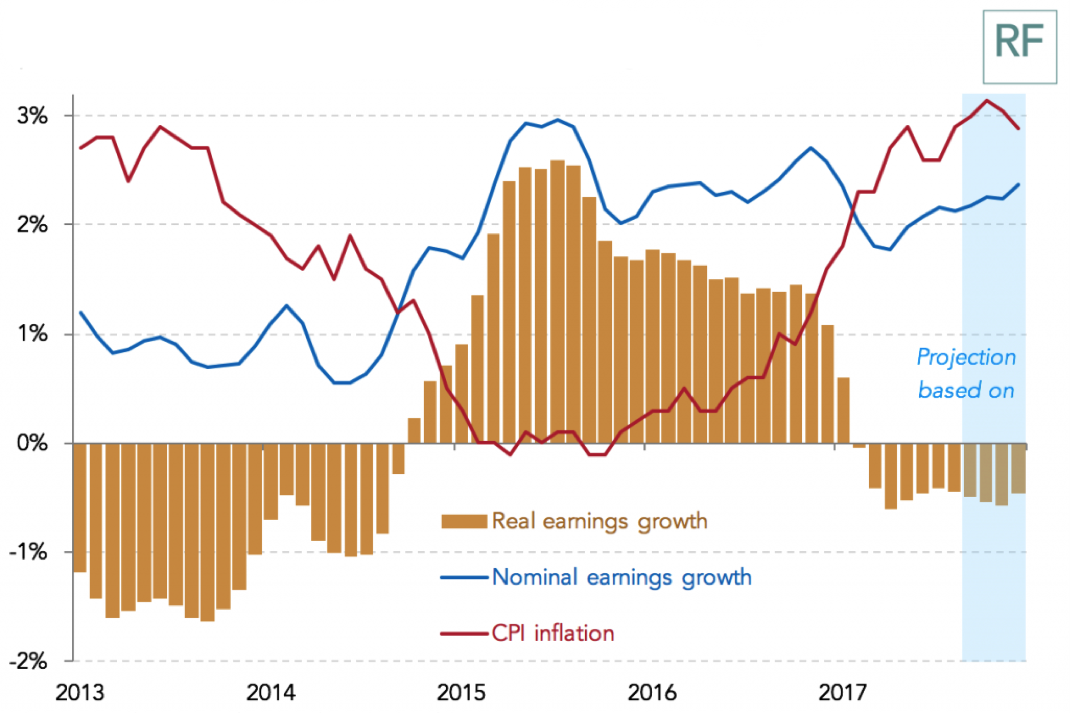

But the good news on employment has failed drastically to translate into a pay rise. A new squeeze on Britain’s median pay began in February 2017 (Figure 2), ending 27 consecutive months of real pay growth. This was due mainly to the late-2016 rise in inflation, attributable mainly to the weaker post-referendum pound, which pushed real pay down year-on-year despite nominal pay growth consistently topping 2% since early 2015.

Newly-released October 2017 data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings confirms that the new pay squeeze turns up in HMRC data too. Most observers don’t expect inflation to persist at its current level throughout 2018, as the effects of currency devaluation ‘pass through’, so today’s pay squeeze should change course in 2018. But with nominal wage rises still far below pre-crisis levels, there are few signs that Britain can expect broad-based wage growth in the near future.

Figure 2. Earnings growth and inflation, 2013-2018. Annual growth in average weekly earnings (regular pay) and CPI inflation

Source: Resolution Foundation analysis, ONS and OBR

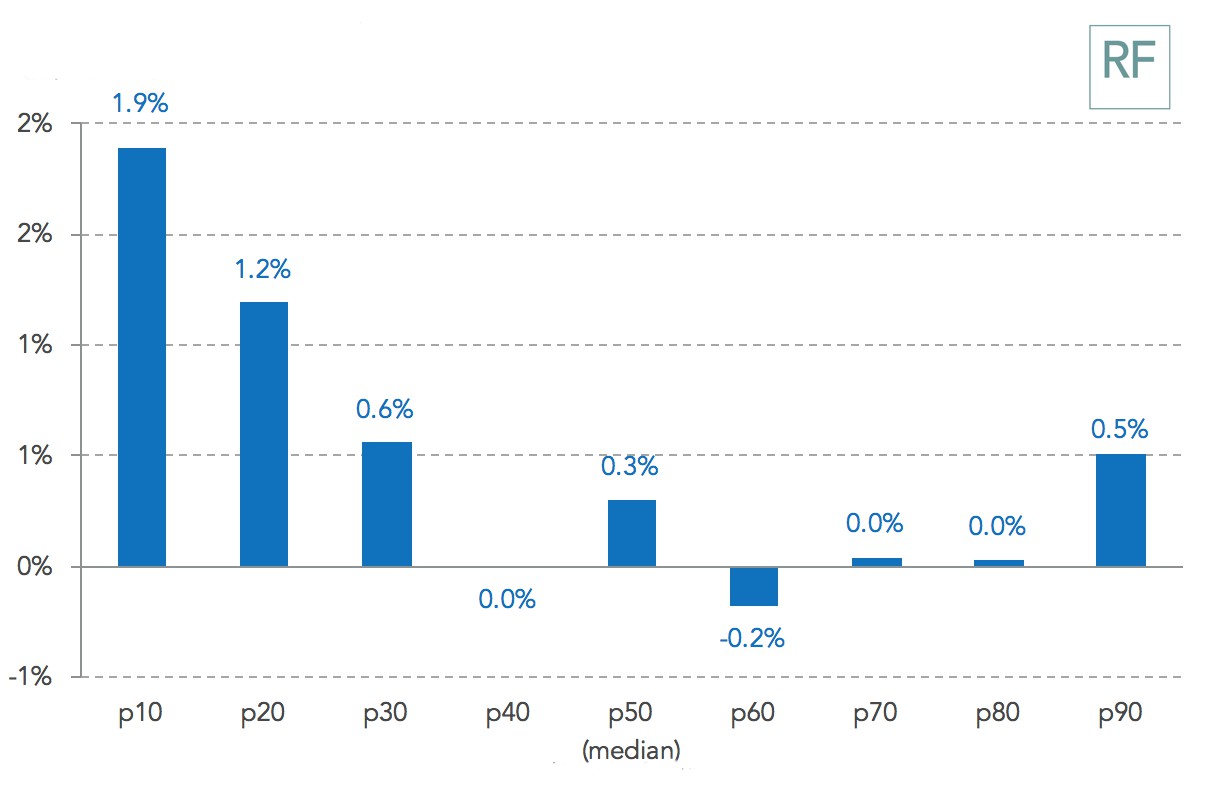

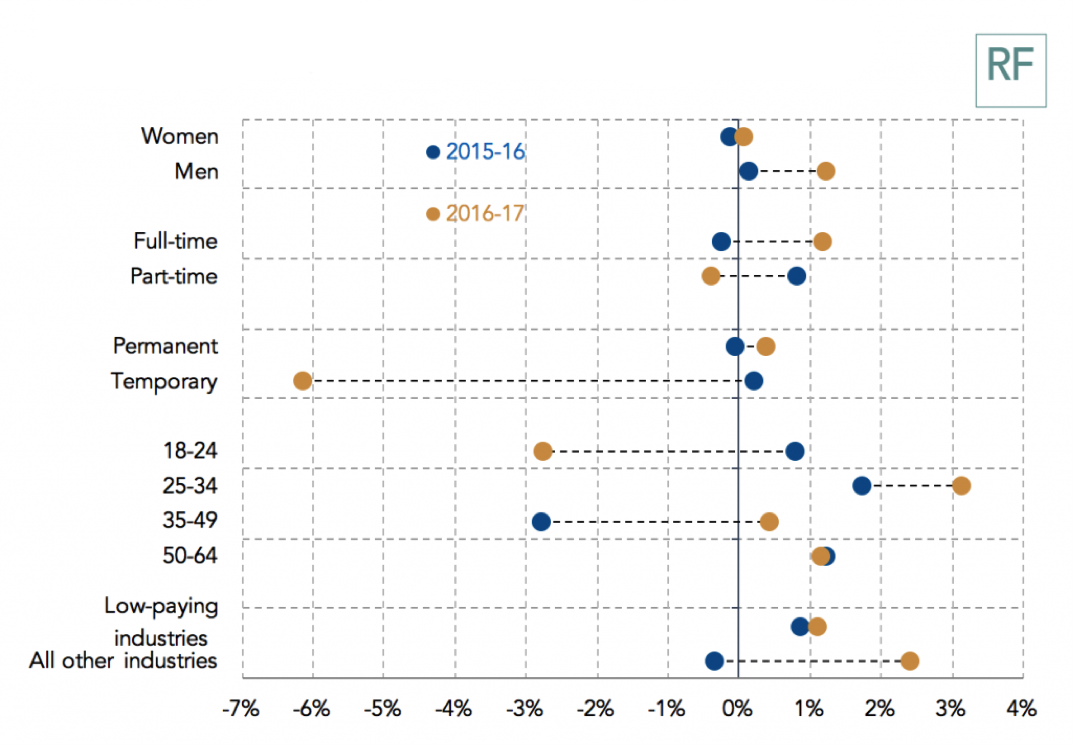

But looking at wages for the lowest-paid, we see the story on pay is much more positive. Recent Resolution Foundation analysis finds that for low-paid workers on or near the National Living Wage (NLW) recent earnings growth is stronger than for higher earners. Pay growth between 2016 and 2017 for the tenth percentile reached 3.5% for full-time workers and 5% for part-time workers. At the Resolution Foundation we use the OECD definition of low pay, as being less than two-thirds of the median hourly wage. Since the introduction of the NLW in 2016, the number of people on low pay has fallen.

Figure 3. Real hourly earnings growth across the distribution in the year to April 2017 (CPIH-adjusted)

Source: Resolution Foundation analysis of ONS, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

The NLW came into force in April 2016 for workers aged over 25, raising the minimum wage from £6.50 to £7.20 per hour in the course of a year. It now stands at £7.50 per hour and will continue to rise faster than median earnings until 2020. This rising wage floor is the main driver of the substantial recent fall in the number of employees who are low-paid, from 20.5% in 2015, to 19.4% in 2016 and 18.4% in 2017. The 2015-16 change was the largest year-on-year drop in low pay since 1977, while 2016 marked the first time since the 1980s that the share of employees who are low paid is below one in five – though a gender imbalance remains, with 61% of low paid workers being women.

To understand more about the impact the NLW is having on people’s lives, the Resolution Foundation organised focus groups in August 2017 for people on wages at or close to the minimum. Few participants reported much of an increase in their wages in the last two years, irrespective of whether they were working full- or part-time or receiving in-work benefits.

Though each of the participants had something positive to say about elements of their work, many were frustrated with their employment and living standards for a range of reasons that go beyond pay alone. Shifts continue to be long and poorly planned, managers continue to give little appreciation and recognition, opportunities for progression in seniority and pay remain limited (particularly for workers with young children), and employers continue to expect greater flexibility around employment than most employees would like to give.

In a tightening labour market where pay is still stagnating, it is possible that job quality will improve before pay does, as suggested by 2016’s halt in the rise of zero-hours contracts. What we do know is that growth in temporary employment fell sharply between 2015 and early 2017 (Figure 4), while permanent employment growth moved slightly from zero up to 0.4%.

Figure 4. Change in employment (seasonally adjusted): UK, 2015 Q2 – 2017 Q2

Despite the NLW helping the lowest paid, it is not (yet) leading to any broader shift away from the recent British model of low-skill, low-paid work. Projecting forward to 2020, if policy continues on its current track, we expect the NLW to continue to reduce the number of employees on low pay from 5.1 million in 2016 to 4.3 million by 2020.

But rather than helping eliminate low pay, the NLW is more likely to lead to greater clustering of employees around the minimum wage floor, with the number of employees earning at or close to the NLW predicted to almost double from 1.9 million in 2016 to 3.7 million in 2020.

Such clustering will further increase the salience of questions about pay progression. Our recent study of pay progression for the Social Mobility Commission found that of those employees on low pay in 2006, only one in six had ‘escaped’ long-term on to higher pay by 2016, while one in four remained stuck on low pay throughout the ten-year period. So, even ten years ago, when a smaller number of employees were clustered around the minimum wage, low paid work was rarely acting as a stepping-stone on to higher pay.

In light of these recent changes for Britain’s low-paid workers, the Resolution Foundation proposes three immediate areas for policy reform:

- First, the government needs to reset the UK’s reliance on low-paid, low-skilled work, with its upcoming industrial strategy giving it a good chance to do so. In recent years the majority of people living in poverty have been in working families. A good way to improve this situation would be to focus on raising productivity in major employing but low paying sectors like retail and hospitality.

- Second, government can help legislate to improve routes out of highly variable shifts or zero-hours contract work. The upcoming response to the July 2017 Taylor review offers an opportunity to set out policy in this direction.

- Last, employers also have a role to provide better training and progression opportunities to existing workers. This should prove a wise investment in the current tight labour market, especially as EU migration is likely to fall as the Brexit process goes on. Easy changes that could be made include widening the range of jobs offered to non-graduates.

So, although the National Living Wage has led to a significant and welcome boost to the pay packets of Britain’s least well-off workers, significant challenges remain. It is incumbent on the government to find ways to work with businesses – on a sector-specific basis – in order to ensure people don’t keep getting trapped at the very lowest end of the pay spectrum by creating progression opportunities into good quality, well paid roles.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post was originally published by LSE British Politics and Policy.

- The post gives the views of the interviewee, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Untitled by M, under a CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

George Bangham is Researcher at the Resolution Foundation.

George Bangham is Researcher at the Resolution Foundation.