A financial inclusion-focused entity recently engaged us to exercise due diligence on a working capital microcredit venture, with the intent of investing $1 million in equity in the business. Chief amongst the requirements was the evidence of employment creation brought about by the extension of credit to micro, small and medium enterprises. This was illuminating on two fronts. On one hand, it reinforced our belief that there is a growing appetite for relatively small-size deals, a much-needed shift in investment focus in Kenya and Sub-Saharan Africa at large. On the other hand, it awakened new possibilities with regard to the perception and understanding of social impact in the Kenyan landscape.

Fast-growing and niche start-ups have often defined the cherry picking of Africa-focused social impact investors. However, the continent’s macroeconomic environment slowdown has affected the business landscape. The search for the blend of promise of return while simultaneously achieving social impact has become elusive. The social impact investment space in many parts of the continent today finds itself at a point of possible inflection from the overarching search for scalability in business ventures to the pressing need to scale investing beyond the traditional focus. The reality of this shift in the operating environment is necessitating revision of the optic through which social impact investors perceive Sub-Saharan African opportunities.

In Kenya, this is bringing to the fore the social impact potential held by the vast micro (annual turnover of less than $ 4,854 and less than ten employees), small (annual turnover in the range $ 4,854 ─ $ 48,543 and between ten and fifty employees) and medium enterprise (MSME) segment of the economy. Three factors converge to make this rethink a potentially significant game changer in ‘crowding in’ social impact-targeted investment into the country:

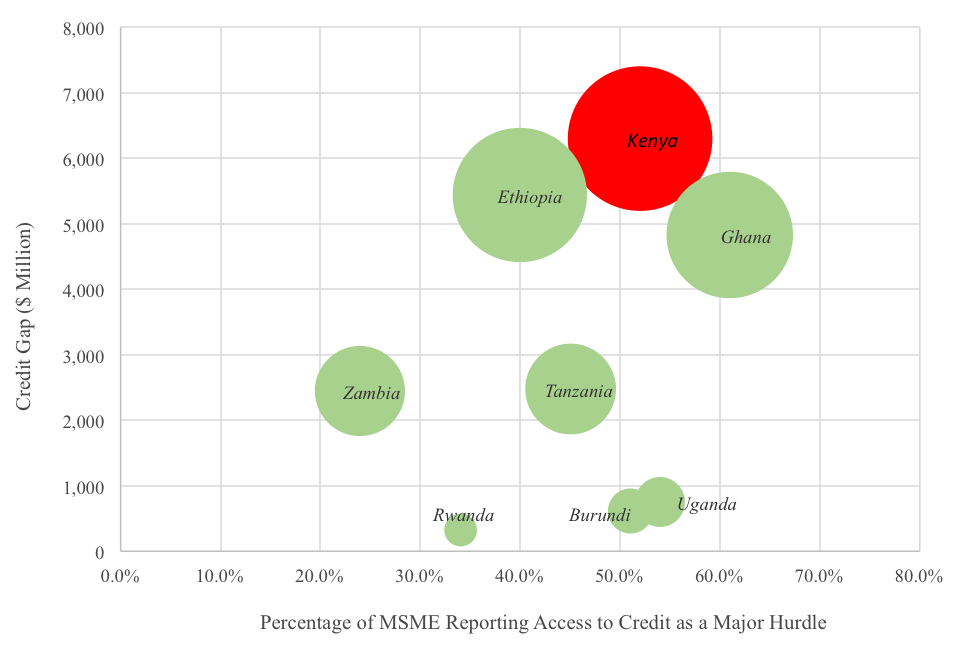

- MSMEs face significant funding challenges despite being the main engine of employment creation. Between 2015 and 2016, 87.3 per cent of all jobs created in Kenya were in the MSME-dominated informal segment of the economy. The significance of MSMEs within the social impact paradigm is amplified when viewed within the context of Kenya’s high unemployment and the need for creation of gainful employment for a growing pool of youth. This pivotal position notwithstanding, the segment continues to face considerable hurdles, chief of which is access to capital. The MSME funding gap (an estimation of both the unserved and underserved funding) in Kenya is $6.3 billion, making it the largest in Eastern Africa, and larger than in a number of peers in sub-Saharan Africa such as Ghana and Zambia. Further to this, the fact that most MSMEs rely on family/own funds to drive operations (72 per cent of MSMEs rely on family for capital) and shortage of funding is the main reason for closure of business (accounting for 30 per cent of closures) point at the urgency with which funding constraints ought to be addressed to unlock the potential of this segment of the economy

Figure 1. MSME Credit gap and access to credit

Source: International Finance Corporation

- Kenya is the hub of social impact investment in East Africa, which in 2015 reportedly stood at about $650 million and $3 billion for non-development finance and development finance investors, respectively. As such, the country is well positioned to leverage this status in realigning the interest of social impact investors towards MSMEs. The 2013 passage of the Micro and Small Enterprise Act, for instance, provided a major shot in the arm, giving form to a hitherto amorphous segment of the economy. By and large, this Act not only provides a clear regulatory framework for MSMEs, but more importantly brought to investors visibility of the potential in this segment. This is not to suggest that sourcing viable investments within MSMEs has been made significantly easier but that periodic surveys now allow us to make sense of developments within this segment of the economy

- Adoption of the Banking Amendment Act 2016 was followed by a deceleration of credit infusion into the private sector, afflicting largely retail borrowers and MSMEs perceived to be high risk. This has served as an awakening to the pressing need for alternative sources of finance for early-stage and businesses perceived as having high risk. Since adoption of the Act, growth in credit to the private sector has plunged from 7 per cent (July 2016) to 1.5 per cent (June 2017) whilst credit to the government has surged from -8.4 per cent to 15.8 per cent in the same period, respectively, a likely indicator that businesses are becoming increasingly disenfranchised as commercial banks opt for safer lending to the government

Hurdles remain despite promising opportunity

These bright spots notwithstanding, the following factors are likely to present hurdles to social impact investors’ shift towards the MSME space in Kenya and other African economies:

- Existence of viable exit opportunities will be one of the main risks for would-be investors targeting the MSME space in Kenya. Whilst Kenya boasts of relatively developed capital markets, by African standards, that would provide a viable platform for exit through Initial Public Offers (IPOs), lack of activity by MSMEs at the exchange puts into question the use of local exchanges as a realistic exit option. Despite the roll-out of the Growth Enterprise Market Segment at the Nairobi Securities Exchange in 2013, four listed entities out of a target 16 by the end of 2016 points at lethargy that undermines confidence.

- Small size investments, which on the whole render most potential investee companies relatively unattractive. This notwithstanding, it is imperative that social impact investors perceive this as an opportunity to fill the financing gap and tailor packages suitable for this segment of the market.

- The investment readiness of a number of MSMEs is also likely to present a major challenge in the quest to have more social impact investors tap into the segment’s potential. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, about 22 per cent of micro enterprises do not keep any form records. This information gap presents a major challenge for would-be investors.

The search for companies with clear exits combined with the reality of a lack of short-term avenues for such exits presents a quagmire for impact investors and a real challenge to the standard 5-7 year time horizon for most of private equity type investments. Instead of dismissing the MSME sector for having limited exit opportunities, impact investors should reconsider the investment model and focus on long-term holding structures, which can continuously grow and gain the requisite scale to become regional financial institutions. These would be able to accomplish exponentially more impact when reaching a critical mass, while keeping a sharp focus on the real reason why the investment was made in the first place.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- Correction: Due to a typo by the editor, we had used the wrong percentage in the fourth paragraph. It has now been corrected to 87.3 per cent.

- This blog post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Small loans widen horizons for the poor, by Africa Renewal, under a CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 licence.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Julio de Souza is the Director of Small and Medium Enterprise and Impact Finance at StratLink Africa and has previously worked with United Nations Development Programme (Kenya and Uganda) focusing on private sector development and co-founded Nuru Energy East Africa, a social enterprise in the renewable energy sector.

Julio de Souza is the Director of Small and Medium Enterprise and Impact Finance at StratLink Africa and has previously worked with United Nations Development Programme (Kenya and Uganda) focusing on private sector development and co-founded Nuru Energy East Africa, a social enterprise in the renewable energy sector.

Julians Amboko is a Senior Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

Julians Amboko is a Senior Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola. He tweets at @AmbokoJH

Konstantin Makarov is the Managing Partner at StratLink Africa Ltd. He is responsible for launch of African practice and oversight of all Sub-Saharan African and South East Asian transactions at StratLink Africa. Previously, he was directly responsible for market entry of US and CIS based companies into Sub-Saharan Africa and has been involved in a wide scope of activity focusing on emerging economies in Africa and South East Asia.

Konstantin Makarov is the Managing Partner at StratLink Africa Ltd. He is responsible for launch of African practice and oversight of all Sub-Saharan African and South East Asian transactions at StratLink Africa. Previously, he was directly responsible for market entry of US and CIS based companies into Sub-Saharan Africa and has been involved in a wide scope of activity focusing on emerging economies in Africa and South East Asia.

A very competent article and just the sort of thing we would like to see more of in the LSE Business Review. I’d like to get the whole report – and hope to see the findings of the study available to as wide an audience as possible. What do I particularly like about the article? – Firstly, It identifies an area that needs to be the real focus for social impact investing. There is so much out in the “market” about impact investing but little with any focus – some of the stuff I’ve seen up close and personal in this new ‘field’ is a bit wishy washy – in my books investing requires impact (almost as a matter of definition) – and in many cases I just don’t see it. I see it here – investing in capital for MSME lending has potential for impact. We need to also focus on measuring it – hopefully the article will attach additional funding for that purpose.

Secondly I like the way the study has both quantified the requirement for Kenya and ranked it in respect of the region.

Lastly it has highlighted a key issue in SSA – deficit funding by Governments and the super attractive “investment” opportunities ii creates in T Bills and other Government backed paper. In some ways I liked the idea of the South African Government to pressurize commercial banks to achieve a certain level of MSME lending in their total loan portfolio.