![]()

Experts in the field of entrepreneurship recently met at the LSE to discuss reform strategies proposed in a new policy brief, which seeks to promote entrepreneurship in the UK. Mark Sanders, associate professor at the Utrecht University School of Economics, presented on behalf of the Financial and Institutional Reforms for Entrepreneurial Society (FIRES) research team, following the publication of its seven step approach to stimulate entrepreneurial reform.

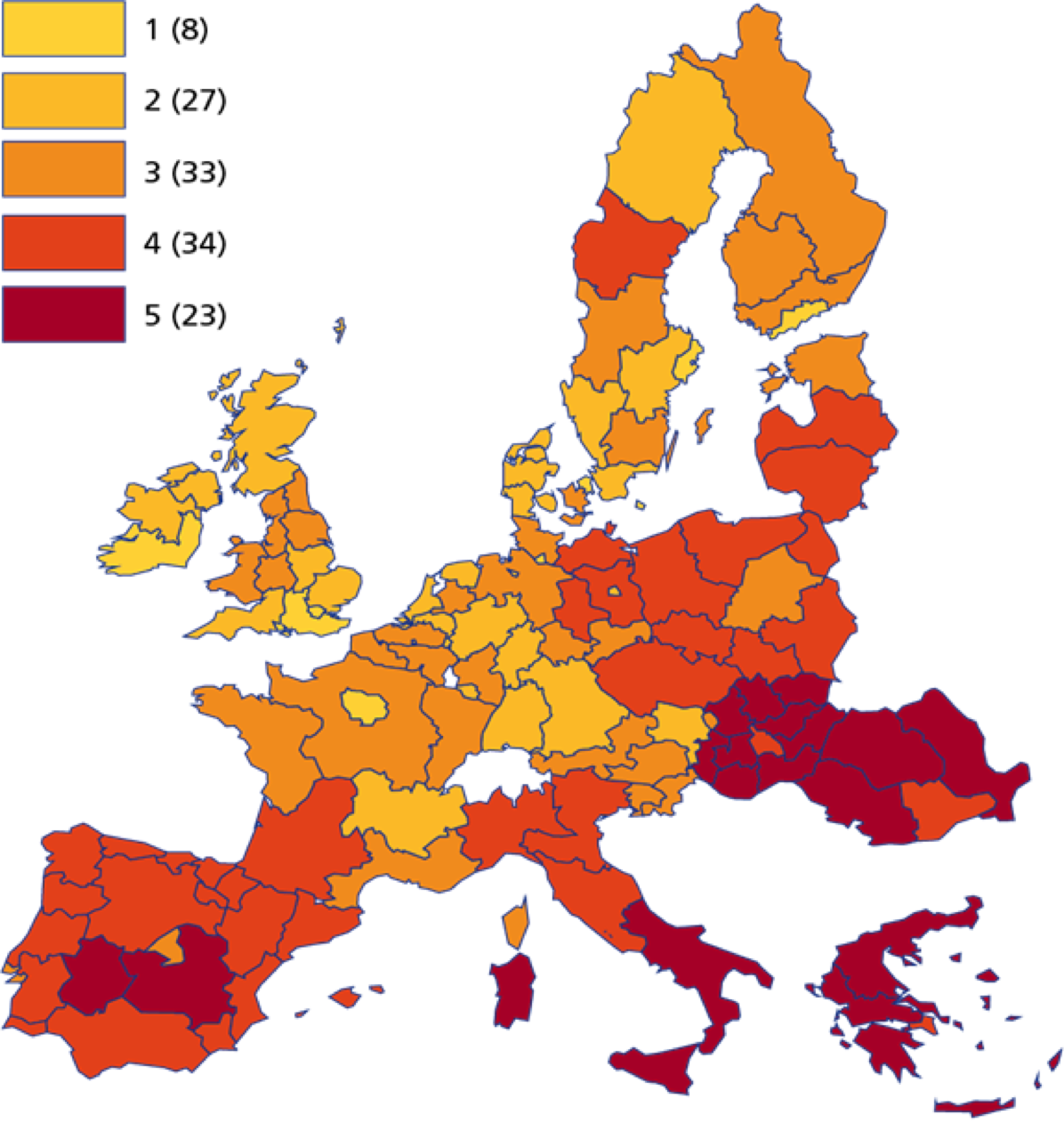

Dr Sanders highlighted a mostly positive evaluation of British entrepreneurship, in comparison with the picture in much of continental Europe. The UK’s relatively good performance of entrepreneurial activity and considerable regional variation – though not as wide as other EU countries – can be seen in Figure 1 below. The lighter shades imply higher levels of entrepreneurial activity in a region.

Figure 1. Entrepreneurial activity in European regions

Policy intervention

The UK was found to perform relatively well in comparison to other European economies especially in terms of its entrepreneurial ecosystem of liberalised markets, deep formal financial markets, strong science and knowledge creation and a powerful legacy of protection of intellectual property rights (IPR). However, the UK system based on market forces with policies centred on deregulation may have begun to reach the point of diminishing returns; it may be time to consider more pro-active government policy-making.

Strength and weakness

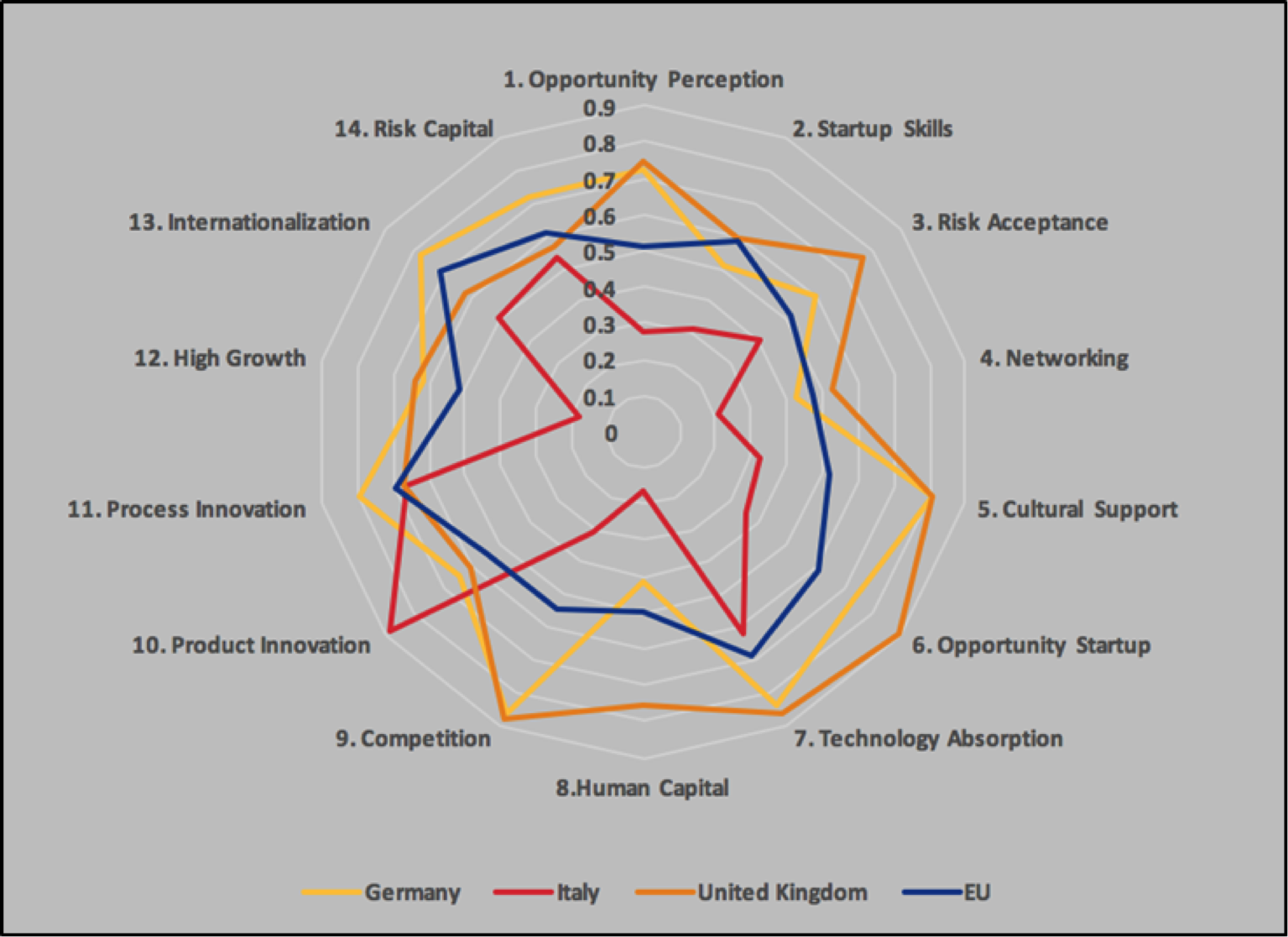

Figure 2 below uses 14 so-called pillars of entrepreneurial actions (broadly the attitudes, abilities and aspirations of entrepreneurs) to illustrate areas of strength and weakness in the UK relative to the European Union as a whole and selected countries. It reveals that the UK has a comparatively strong but rather unbalanced entrepreneurial ecosystem. It excels in ‘opportunity recognition’ and ‘risk acceptance’ by EU standards, but less so on ‘networking’ and ‘start-up skills’. Furthermore, the UK lags slightly relative to the EU average on ‘internationalisation’ and ‘process innovation’ and generally scores poorly in parts of the upper-left of figure 2 (entrepreneurial aspirations, pillars 10-14). While the UK is strong on radical innovation and identifying entrepreneurial opportunities, it is weaker in bringing those projects to fruition.

Figure 2. UK performance in the pillars of entrepreneurial activity compared to EU

Key constraints underlying pillars include labour skills. There is an uneven distribution of labour force in the UK where there is a lack of incentive for people to stay outside of London (or go back home) to contribute to growing businesses that have severe labour shortages. Firms need incentives to invest in firm-specific human capital, and public policy needs to consider the weaknesses in the supply of early stage entrepreneurial finance.

Policies to reduce failure and accelerate scale-up are also proposed to be as important as policies to generate more entrepreneurship. It was argued that in the US, start-ups may grow more rapidly, while in Germany, there might be fewer start-ups but they are more likely to survive and prosper. Entrepreneurial attitude in the UK is abundant, but the results in terms of actions lag and there is a need to focus on learning from failure in the entrepreneurial process.

Finally, while the UK ecosystem rewards entrepreneurial success it is not very inclusive, with resources highly concentrated in London and the South East. There is a visible centralisation of the entrepreneurial resources in London, which is now starting to be perceived as a competitor to Tel Aviv or Silicon Valley. Yet, the city is only attracting a narrow demography. Jonathan Levie, professor at the Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship, expressed his deep concern about this centralisation of entrepreneurial activity and resources in the UK into London. He illustrated the problem with data indicating a huge increase in company creation and growth in London boroughs such as Hackney (around Silicon roundabout), whereas in other regions of the UK the rate of company formation and growth is much slower. The UK’s political and policy centralisation is depleting regional energy and distorting national culture.

A reform agenda for the UK

Dr Sanders presented a set of general recommendations based on open access to knowledge, more inclusivity in the entrepreneurial process and levelling the playing field regionally.

As an example, FIRES proposes experimenting with open intellectual property rights to ensure access to and commercialisation of knowledge. However, participants questioned the proposal of abandoning IP protection and pointed out that regulation regarding patents seems more relevant. Regulation regarding standing patents were seen as blocking growth by allowing patent protection to continue for twenty or thirty years. It was suggested instead that one could either increase renewal fees of patents, or open IP systems to radical change towards “Open Source”. Also, some participants pointed out the importance of keeping IP laws to encourage investment, as it is one of the few tangible components of an entrepreneurial project upon which investors can make evaluations about where they should invest.

Finally, the discussion noted the ambiguity of the notion of entrepreneurship itself. It was argued that the language of entrepreneurship should be broadened to make it more specific and inclusive so that different types of entrepreneurship from restaurants, to taxi drivers, to industrial production could be independently identified, and effectively addressed by specific corresponding policies. It was also stressed that the language on entrepreneurship is mainly focused on the international success stories and fails to include all varieties of entrepreneurs, ranging from multinational fintech start-ups to the local plumber starting his own business.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The LSE round table, held on 26 April 2018 permitted leading UK investors, policymakers and entrepreneurship scholars to discuss the policy brief on the FIRES-reform strategy for the UK . Read the Policy Brief and the Policy Roundtable Report.

- This blog post appeared first on Management with Impact, blog of LSE’s department of management. It is based on Policy Brief on the FIRES-reform strategy for the UK, no.19-07/April 2018

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by osde8info, under a CC-BY-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Saul Estrin is professor of management and founding head of the department of management at LSE. His areas of research are emerging markets, with a particular focus on entrepreneurship and international business issues. Professor Estrin has published more than one hundred papers in scholarly journals as well as numerous chapters and reports. He is co-author of the policy brief on FIRES-reform strategy for the UK.

Saul Estrin is professor of management and founding head of the department of management at LSE. His areas of research are emerging markets, with a particular focus on entrepreneurship and international business issues. Professor Estrin has published more than one hundred papers in scholarly journals as well as numerous chapters and reports. He is co-author of the policy brief on FIRES-reform strategy for the UK.