Calculating the costs and benefits of trade unions has always been a controversial subject. Andreas Hauptmann argues that neither economically liberal regimes, nor strict government controls can provide for optimal levels of occupational health and safety standards. Rather, trade unions can help fill this gap by identifying issues in the workplace more quickly and by this they increase production and welfare. Membership of unions experienced a large rise in the early 20th century, but this has since fallen in most countries. One explanation is the promotion of better health and safety legislation. In this sense unions have been a victim of their own success as their importance has declined with better workplace standards.

Calculating the costs and benefits of trade unions has always been a controversial subject. Andreas Hauptmann argues that neither economically liberal regimes, nor strict government controls can provide for optimal levels of occupational health and safety standards. Rather, trade unions can help fill this gap by identifying issues in the workplace more quickly and by this they increase production and welfare. Membership of unions experienced a large rise in the early 20th century, but this has since fallen in most countries. One explanation is the promotion of better health and safety legislation. In this sense unions have been a victim of their own success as their importance has declined with better workplace standards.

Trade unions have a long history in many industrialised countries. The merits and downsides of organised labour representation have been heavily disputed ever since their creation. Of course, it is widely acknowledged that some groups, employees and employers alike, have benefited from union work. However, the question remains: can society as a whole benefit from collective labour representation?

In a recent study, economists Klaus Wälde and Alejandro Donado argue that unions indeed can provide valuable services that increase economic activity and social well being. In fact, when it comes to occupational health and safety standards, neither the government nor a laissez-faire economic system have the means or the incentives to assure optimal production and welfare. Unions can fill this gap and can increase output and welfare.

The introduction of new technologies and unintended side effects

Economic growth and development heavily depend on the exploration and introduction of new technologies and processes. These improvements may include the invention of productivity enhancing techniques, the discovery of new materials or a reorganisation of work related processes. However, increased productivity by using inputs more efficiently may also come with unintended side effects. One prominent example is that the introduction of a new technology may have negative health implications, due to the inhalation of toxic substances, the incorrect usage of equipment or overly repetitive motions.

It would be beside the point to attribute negative health implications to the carelessness of the inventor. More likely, health effects of any kind may simply be unknown at the time of introduction but rather reveal themselves bit by bit. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible for a single worker to prove that their current working conditions have negative health implications. It may very well be that bad health is caused by subjective predetermination, habits or entirely different reasons.

Promoting workplace improvements by collective representation

In contrast to this, a union, as an organised entity of individuals, has the means to gather information for a much larger number of workers and in a much shorter timeframe. If several workers in the same workplace or the same occupation are showing the same symptoms, it is far more difficult to negate any impact of the workplace. However, increased incidences are no proof of causation in a scientific sense. Employers, insurance companies and even governments may require convincing evidence before allocating costly resources to improve workplace standards. This is where a second advantage of unions comes into play. A union can act as a collective voice and raise public awareness, initiate a political debate and lobby for broader support.

While better health is a desirable achievement in its own right, it also serves more general interests. Fewer days of sick leave in effect increase the aggregate labour supply, and the evidence shows that this positive effect outweighs the costs of introducing occupational health and safety standards. Additionally, for workers who do not stay at home but rather choose to work with some detriments, it may be considered that better health increases their work qualitatively. Also employees may increase their exerted working effort if they feel well taken care of.

The rise and fall of unions

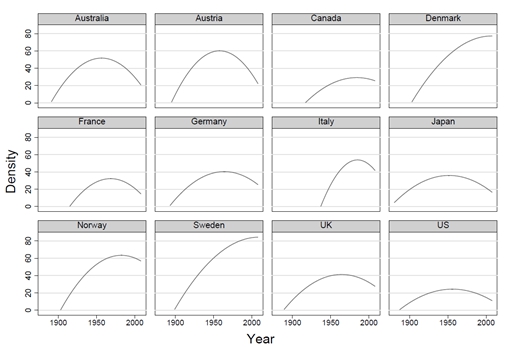

The authors apply their view of the beneficial effect of unions to understand the rise and fall of unions over time. Despite cross sectional differences, the evolution of union power, when measured by union density (a calculation based on the number of enrolled union members as a proportion of all those employees potentially eligible to be members), reveals an interesting inverted U-shaped pattern as displayed in Figure 1. The framework presented herein can further help to understand the initial increases and its reversion afterwards.

Figure 1 – Trade union density in 12 countries 1880-2008

The Industrial Revolution during the nineteenth century may be seen as an era characterised by the numerous and pathbreaking introduction of new technologies. Initially, health effects are unknown and are only revealed sequentially to individual workers. After more and more workers realise that joining a union is accompanied by better health and safety standards, trade union density increases. Once certain standards are verified, they are introduced by government legislation and there is less benefit from union membership for the individual worker. The irony is that from this perspective union importance decreases because they are doing a good job.

Although the development is qualitatively the same for all countries, there are substantial differences between countries in terms of levels and the timing of the union membership peak. This can be explained if there are differences between countries towards external representation and public institutions. In this respect, a greater emphasis on individual freedom in the US compared to some European countries can explain the low and early peak of union density in the US.

Unions as insurance

Some important lessons may be learned from the line of reasoning above: Given uncertainty about the potential side effects of new technologies, it comes as no surprise that unions and other forms of worker representation have first opted for insurance mechanisms. This is especially true if employers and governments face a conflict of interest when it comes to workplace improvements: particularly the ones not yet scientifically established. It also has to be mentioned that the opposing interests of employers and employees arise from the assumption that there are no (or few) firm-specific individual requirements. In this case, if a worker becomes ill, they can easily be replaced by another one. While this may have been a realistic picture during the days of the industrial revolution, it may have become less relevant in some of today’s occupations.

Given this background, a decline in union importance may represent a better understanding of health related workplace issues. While this may be the case for physical illnesses, the picture is less clear when it comes to psychological impairments. For instance, public discussion about the so called ‘burn-out syndrome’ and its relation to modern labour standards of work organisation has only started. Viewed in this light, unionism may not be condemned to lose further importance, but rather help to increase our understanding about new developments.

This article is based on Donado, A and Walde, K. (2012). How trade unions increase welfare. The Economic Journal 122 (September), 990–1009

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/VzclpR

_________________________________

About the author

Andreas Hauptmann – Institute for Employment Research

Andreas Hauptmann – Institute for Employment Research

Andreas Hauptmann is a researcher at the Institute for Employment Research in Nuremberg (IAB) in the department “International Comparison and European Integration” and a Ph.D. student at the University of Mainz with Klaus Wälde. His research focuses on Internationalization, wage formation and industrial relations.