With no deal reached between Greece and its creditors, there remain doubts as to whether the country will be able to make its next debt repayment to the IMF. Gregory T. Papanikos assesses the consequences of a ‘Grexit’ for the people of Greece. He argues that the Greek government has proven itself incapable of negotiating with other members of the Eurozone and that the fallout from Greece leaving the euro would fall disproportionately on the poor.

With no deal reached between Greece and its creditors, there remain doubts as to whether the country will be able to make its next debt repayment to the IMF. Gregory T. Papanikos assesses the consequences of a ‘Grexit’ for the people of Greece. He argues that the Greek government has proven itself incapable of negotiating with other members of the Eurozone and that the fallout from Greece leaving the euro would fall disproportionately on the poor.

A static economic analysis would have concluded that Greece should not have joined the Eurozone in 2001. The same analysis would have advised Greek politicians against Greece’s integration into the European Union in 1981. Both pieces of advice would have been wrong. The Greek economy has evidently benefited from its membership in the European Union as well as the Eurozone, as it continued to experience an unprecedented economic growth from the post-World War II period. And this, despite the recent economic crisis which slashed Greece’s GDP by 25 per cent in a span of five years.

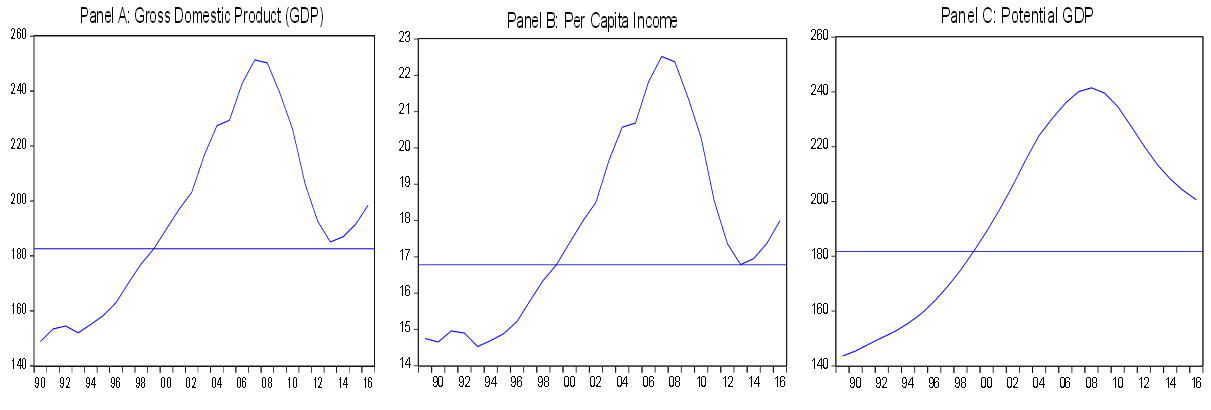

As I have documented elsewhere, the lowest level of Greek GDP (and per capita income) in the 21st century is still higher than the highest value of GDP (and per capita income) experienced by the country in the entire 20th century. Even more importantly, the lowest potential GDP of the 21st century was higher than the highest value of the 20th century. Additionally some evidence exists that income distribution has improved. The Figure below illustrates this picture.

Figure: Greek output, per capita income and potential output (1990-2016; click to enlarge)

Source: Eurostat (AMECO database)

Wealthy Greeks will benefit from a Grexit

Today Greece is one of the richest countries in the world both in terms of its per capita income and wealth. It would appear even wealthier in the international figures if the Greek informal economy is taken into consideration. As I have examined elsewhere, this wealth should be taxed, and the revenue proceeds would be more than sufficient to serve the Greek sovereign debt. There is no need for a bail out. But the wealthy Greeks do not want to pay any taxes. Most of them never did. Recently they were forced for the first time to pay a tax on their property (wealth) which was met with fierce resistance. Most of them voted for a Syriza government.

Despite their left-wing rhetoric, the new government wants to abolish (it now talks about ‘reducing’) the property tax and to substitute it with an increase in the Value Added Tax which will harm poorer households. A Grexit would have made things much easier for wealthy Greeks and of course the Syriza government. As was done many times in the pre-euro years, a Greek government with a money printing machine in its hand would flood the market with inflationary national currency. An inflation tax is a boon for the wealthy, especially those who have deposits in foreign banks. Poor Greek households will therefore pay the full price for the economic crisis if a Grexit occurs.

The euro’s exchange value is the problem

A Grexit benefits the state nourished individuals of the Greek economy, including the notorious employees of the public sector and state controlled enterprises. The greater part of them voted for Syriza. Very few were surprised when the new government mandated an increase of 10 per cent in the salaries of employees of the state controlled electricity company. And it is not an accident that the Minister who decided on this salary increase is in favour of a Grexit.

A Grexit would make Syriza’s work much easier in serving the interests of these individuals, who make up close to 30 per cent of the Greek electorate. Also Germany’s economic interests would be served better if Greece left the Eurozone. The reason is very simple. Germany’s economy needs a strong euro. This was the case in the first decade of the euro’s existence. On the other hand, the Greek economy would have benefited tremendously from a weak euro. Greece in the Eurozone will always exert a downward pressure on the value of the euro.

Thus, from an economic point of view, Germany would profit from a Grexit. If Germany could minimise the political costs and the economic side effects of a Grexit, it would welcome such a prospect. This is the reason why voices in favour of a Grexit that come from the left and right of the political spectrum of Greece serve Germany’s economic interests by making a Grexit politically acceptable both to Germany and Greece. Germany has suggested on many occasions that it would be there to help with a Grexit.

As I have explained, the real Greek effective exchange rate of the euro was 20 per cent overvalued between 2002 and 2014. This has had a negative impact on Greek economic growth. A 10 per cent lower value for the euro during this period would have increased the rate of growth of per capita GDP by almost an additional 1.25 per cent per annum. This would have made the economic recession less severe. During the crisis years, it seems that the ECB’s monetary and exchange rate policy favoured particular countries in the Eurozone, and Germany emerged as the big winner. In 2014 and 2015, the euro’s value has fallen and the Greek economy was able to show some signs of recovery. Thus, for Greece it is the value of the euro which is the problem and not the Eurozone itself.

The ECB’s new policy of quantitative easing will help the Greek economy because it will exert a downward pressure on the value of the euro. The benefits will be enormous for poor Greek households and of course the healthy Greek private sector which does not depend on government support programmes. The new government wants to reinstate the notorious system of state nourished parasitical capitalism: and all this in the name of a left-wing ideology. Very few were surprised when the ‘left-wing’ Syriza formed a coalition government with the right-wing Independent Greeks, as they both serve the same interests.

The failure of the Syriza government

Not all Syriza members are in favour of a Grexit. But the new government has proven itself incapable of negotiating with the other Eurozone countries primarily because it has been enslaved by its outdated ideological obsessions. It represents those segments of the Greek electorate who are responsible for the current plight of the Greek economy. Even worse, the new government has neither the experience nor the academic knowledge to deal with the challenges of negotiating with other Eurozone members.

The Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has never worked in his life. He has spent his life protesting against the ‘system’. His finance minister has no experience in policy making and policy negotiating and his professional academic background is not in the area of economic policy. He has some talent for playing games, especially with the media and his colleagues in the Eurogroup, but both are not fit for the job, as Greeks will soon find out to their cost.

The new memorandum which the Syriza government will sign with the “troika” will undoubtedly be worse than any of the two previous ones and this will be despite a more favourable global, European and Greek economic environment. And this is the best case scenario. The worst scenario would emerge if Syriza, out of desperation, puts on the table the issue of a Grexit – something that would make some German politicians very happy indeed.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council President (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Exeub6

_________________________________

Gregory T. Papanikos – ATINER/University of Stirling

Gregory T. Papanikos – ATINER/University of Stirling

Dr Gregory T. Papanikos is the founder and current President of Athens Institute for Education and Research (ATINER). He is also Honorary Professor of Economics at the University of Stirling.

There is corruption among all classes in Greece not just the wealthy. Claiming wealthy Greeks never paid taxes is plan absurd. The Greek left has gone insane with their class warfare rhetoric (now even voting for a communist leader while trying to pawn themselves off as “moderate” left)

Dear Gregory, I am confused by your analysis.

First, you say that euro membership has benefited Greece, yet the figures posted with your article show that the GDP today is at about the same level it was the year before euro entry. The real growth rate of the Greek economy during its eurozone membership has averaged about 0%. The real growth rate of the Greek economy before euro entry was about 2-3%, depending on how back in history one starts measuring. I have never met a macroeconomist (or any economist for that matter) who would dispute that it’s preferable to live in an economy where nominal income grows by say 6% only to have 4% of it eaten away by inflation, than in an economy where there is no inflation but also no income growth. Are you disputing this?

I agree that a national currency should not be used for the purpose of tax collection via inflation as has happened in the past, but the benefits from its introduction through the ability impose independent monetary policy and force an exchange rate consistent with the clearing of the markets for goods and labor are undisputed among macroeconomists, so I am wondering where you stand here. You acknowledge that Greece’s currency was overvalued for the past decade, yet you attach no economic value to the ability to conduct a currency devaluation if required? This does not seem very coherent.

Furthermore your comments on the redistributive agenda of the Greek government convey that you might be rather misinformed on the issue. You say that property taxes are to be lowered which will benefit richer households. This might have been true in a country like the UK or Germany, but not in Greece where 70% of households are property owners. (see table 1.2 here: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpsps/ecbsp2.pdf ) So this is indeed a tax-cut, but hardly a tax-cut to the rich as we are essentially talking about lower-middle and middle class or even working class households. According to Euclid Tsakalotos, the tax relief will only concern households’ primary residencies. Owners of large estates are, according to the same minister, to be taxed at higher rates than present. Therefore, if the Greek government sticks to its commitments the revamped property tax will have a modest redistributive effect that will favor 7 out of 10 households at the expense of households who own multiple properties. This seems fair enough to me.

That the government plans to raise sales taxes is unfortunate, but according to the EC’s president the insistence on this tax is meant to achieve a primary budget surplus. If the government were to abandon the euro and default on its debt, such need would no longer exist and the greek government could scrap the plan to raise sales taxes.

Finally i’m not sure I comprehend your comments about the 10% rise in the salaries of the energy company, as to my knowledge this salary hike was agreed to between the labor union of the company’s personnel and the previous one (i.e. Samaras led Pasok-ND coalition), but please correct me if my information is wrong.