The feminist movement in Colombia has a long and complex history. Its collective political activities have constructed different subjects made up of multiple identities and political perspectives, yet they have always been united by their desire for peace and their spirit of revolt, writes Erika Rodríguez Gómez (LSE Centre for Women, Peace, and Security).

The feminist movement in Colombia has a long and complex history. Its collective political activities have constructed different subjects made up of multiple identities and political perspectives, yet they have always been united by their desire for peace and their spirit of revolt, writes Erika Rodríguez Gómez (LSE Centre for Women, Peace, and Security).

• Disponible también en español

In the context of the global fight against war, feminists have acted as peacebuilders and brought about negotiated political solutions to different armed conflicts by demanding commitments from the parties involved. They have also advocated not only for the consolidation of peace but also for the enhancement of rights and freedoms for women.

In the case of Colombia, feminists were responsible for the creation of a pioneering, unprecedented body, the Sub-Commission on Gender, as well as the inclusion of a gender focus in the Final Agreement, signed by the Colombian government and the FARC-EP guerrilla movement in November, 2016.

At the same time as these political peacebuilding activities have taken place, feminists have led a struggle for recognition and redistribution around ideals of justice in the economic, political, and cultural domain of women, its ultimate goal being the overthrow of the patriarchal system.

Thus, feminism in Colombia came to be known as such from the era of the struggle for the right to vote in the mid-twentieth century, ushering in what is known from the Western social science perspective as the first wave of feminism, or the suffrage movement. The historical understanding of this social movement as a series of waves or stages has proven to be helpful in situating women’s struggles chronologically in the context of other emancipatory struggles triggered by other social movements, and in the context of the development of industrialised societies in Europe and North America. However, it has also proven to be misleading and overly linear when analysing contexts and subjects as different as those of Latin America, for example.

In that regard, Colombian women’s struggle for citizenship coincided with the initial signs of the emergence of the armed conflict, in which was present not only the controversy concerning political participation, but also the need for redistribution of land tenure. Moreover, what became the second feminist wave (from the seventies to the nineties), in which women began to politicise their bodies and express their sexuality more freely, unfolded in a country with a growing armed conflict where counter-insurgency policies began to be implemented and violence began to intensify. The most important sphere in which this violence occurred was precisely women’s bodies.

As well as demanding the right to control their own bodies, Colombian women who formed part of the second wave had to begin to understand the nature of patriarchal violence and make it a priority for both the state and social organisations. Right from the early nineties, when the conflict began to escalate and the world started to focus its attention on gender issues, Colombian women had gained a good deal of experience in demanding peace without abandoning their revolt. They came to understand that they could be subjects with the ability to take decisions concerning their own bodies, and that the exercise of violence, whether as part of or external to the armed conflict, as a realisation of the patriarchal system, created significant obstacles in their lives.

The third wave of feminism arrived with a new constitutional charter (in 1991) which enshrined equality for women in its text but failed to resolve Colombia’s social, political, and armed conflict, which at that time involved guerrillas, paramilitaries, and security forces fighting for territorial control. Women began to specialise in advocating peace and demanding a negotiated political settlement to the conflict, as well as constructing discourses and practices centred on this objective. The culmination of this stage came with the signing of the final agreement. Women were involved in and able to influence this process to a significant degree (if not as negotiators than at least as participants) thanks to civil-society roles that enabled the positioning of women’s issues and a gender focus.

Their reach was such that the variegated rebelliousness of women from many arenas could converge in the development of the peace process: feminists in the world of academia, in social organisations, in government, and in the rebel movement have been exchanging ideas and opinions for the last four years. In the new FARC-EP political movement, female guerrilla fighters are positioning insurgent feminism as a revolutionary ethical-political concept of reality underpinning their struggle both inside and outside the party.

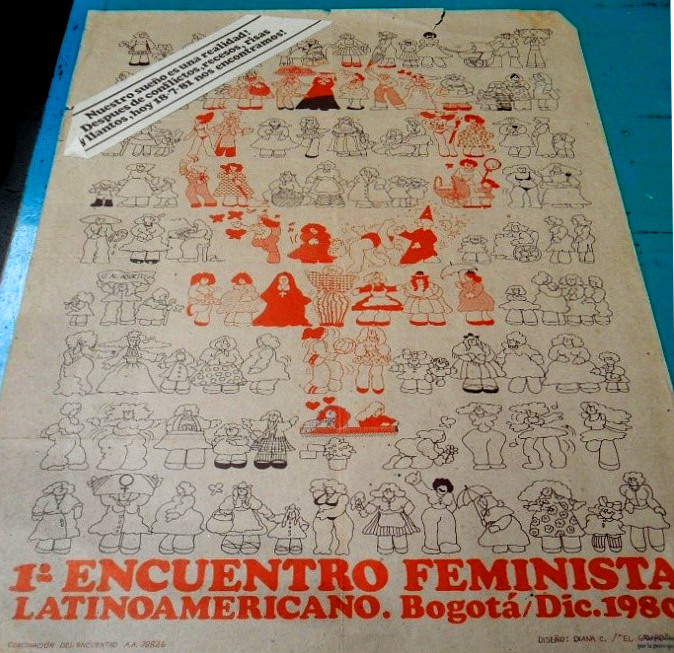

If we recall the inaugural Conference of Latin American Feminists (Bogotá, 1981), which brought together at least 200 feminists from across the region to exchange ideas on women’s liberation, the main topic of debate at that time – and a constant for the last thirty years – was the tension between identifying as a feminist and belonging to a mixed-gender, left-wing political party.

The debate again became public when female members of FARC-EP presented their Thesis on Woman and Gender at the party’s founding conference, as the guerrilla movement had been widely perceived as a patriarchal military structure where women were never anything but victims.

It is important to recognise the legitimacy of women in the guerrilla movement telling their own stories using their own reference points and creating spaces to develop a wide-ranging feminism. Being a feminist necessarily means being a rebel. It means being uncomfortable with the asymmetrical forms of power that shape our public and private lives.

But peace is not immune to such power. It is an unfinished process which has yet to transform patriarchal structures. The building of this more holistic peace is a task that all of us, men and women alike, must take on together.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting