In a context of political dealignment and a fluid multiparty system, corruption scandals and a divisive international court ruling on sexual and reproductive rights have drastically altered the electoral landscape, write Evelyn Villarreal Fernández (State of the Nation Programme) and Bruce M. Wilson (University of Central Florida).

In a context of political dealignment and a fluid multiparty system, corruption scandals and a divisive international court ruling on sexual and reproductive rights have drastically altered the electoral landscape, write Evelyn Villarreal Fernández (State of the Nation Programme) and Bruce M. Wilson (University of Central Florida).

This Sunday, 4 February 2018, will mark the 17th time since the end of the 1948 civil war that Costa Ricans will go to the polls to simultaneously elect all 57 members of the Legislative Assembly, the president, and two vice presidents.

Costa Rican democracy is one of the oldest, best-performing democracies in the Americas, but the upcoming election is marked by general disinterest, voter volatility, and two late-breaking events that have displaced traditional campaign issues. These two events, a corruption scandal and an international court ruling, have combined with a process of political dealignment and the consolidation of a fluid multiparty system to significantly alter the electoral landscape.

Decades of dealignment and multipartism

Historically, Costa Rican politics was dominated by two major parties that routinely garnered more than 94% of the national vote. Since 1994, however, no party has won majority control of the 57-member legislative assembly, and parties find it increasingly difficult to garner the 40% national vote share necessary to capture the presidency.

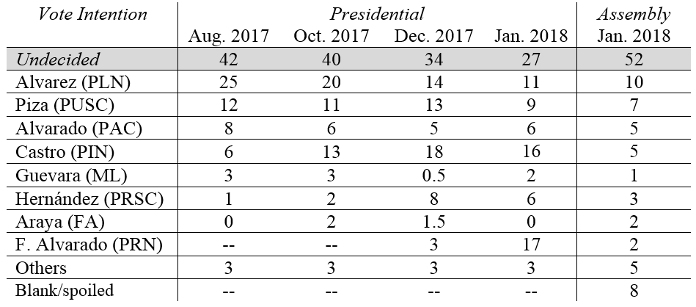

This weakness is compounded by the general instability of party support and increased split-ticket voting, whereby voters back different parties in presidential and legislative elections, for example (see Table 1). The sitting president’s party, PAC, is only the second largest party in congress and has to work alongside deputies from seven other parties.

No clear winner in sight

Thirteen candidates successfully registered with the Supreme Electoral Court for the 2018 presidential election.

A December 2017 poll had Juan Diego Castro, of the emergent Partido Integración Nacional (PIN), as the most popular candidate with just 18% support. The second and third most popular candidates, Antonio Alvarez (PLN) and Rodolfo Piza (PUSC), polled just 14% and 13% respectively. Carlos Alvarado, from the incumbent president’s party, received just 5% support, which represents a major reversal of fortunes for a party that lost the 2010 election by less than 1% and won the presidency in 2014.

But a poll in late January further scrambled the voters’ preferences: evangelical candidate Fabricio Alvarado leapt into first place with 17%, up from 3% the previous month, while the second and third place candidates both lost support.

Enthusiasm for the 2018 election remains low (25%), and the fact that “undecided” voters constitute one third of the electorate has amplified the uncertainty surrounding election day. A second-round runoff is likely.

Shifting priorities in the run-up to the election

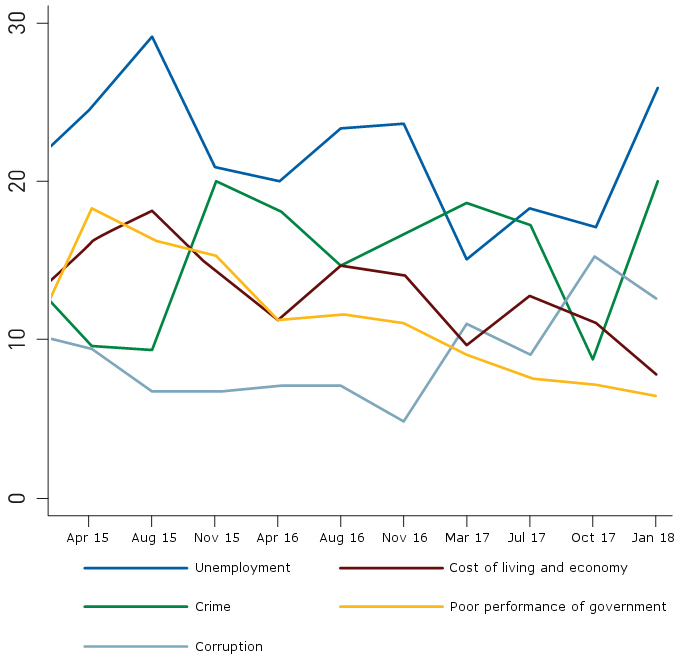

Public perceptions of the main problems facing the country have fluctuated a great deal, though unemployment, corruption, crime, the economy, and poverty and inequality all feature consistently. However, issues of corruption and “morality politics” (regarding sexual and reproductive rights) have emerged so recently as to be absent from polling, yet they have taken centre stage in the closing stages of the campaign.

Corruption old and new

Corruption is a perennial issue – previous scandals have landed two former presidents in jail – and all of the political parties have strong anti-corruption programs.

The recent corruption scandal, known locally as the Cementazo, involved a state bank, money skimmed from large loans, Chinese cement imports, influence peddling, and political patronage. Fallout from the scandal damaged a number of prominent figures and parties (particularly PLN, PUSC, PAC and ML), leading to a decline in support.

But one of the frontrunners in the polls, the relative newcomer Juan Diego Castro (PIN) has avoided being implicated as neither he nor his PIN party were in office during that period. Castro has also taken a hard-line against corruption, promising to “sweep away corruption and put all the corrupt ones in jail.”

The resurgence of “morality politics”

A second major issue that has shaken up voter preferences is the question of sexual and reproductive rights, along with Costa Rica’s status as the only country in the Americas with a state religion.

The issue burst into the foreground in January 2018 when a resolution from the InterAmerican Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) required Costa Rica to legalise same-sex marriage and protect transexual rights.

Initially, many candidates said they would maintain Costa Rica’s tradition of implementing IACtHR decisions, but they quickly switched track once the unpopularity of the resolution became clear.

Álvarez Desanti (PLN), for example, initially supported the ruling but then went on to attack the government for going “behind the backs of the citizens” to legalise same-sex marriage through the IACtHR. He also reoriented his campaign fliers to position himself closer to evangelical voters.

That said, some presidential candidates have been more supportive of the ruling, and a new party for the province of San José (Vamos) includes gay and trans candidates on its party list for legislative elections.

When uncertainty is the only certainty

One clear positive of the democratic environment is that voters have a great deal of accessible, reliable information about all of the candidates and all of the parties’ platforms. All of the major TV and radio news programmes, newspapers, universities, NGOs, and the electoral council have hosted debates and created technological solutions to facilitate access to electoral and party information, to analyse and compare, and to fact-check important news stories.

Yet, with just days to go before the election, many voters remain undecided or threaten to flip from one candidate to another, creating massive uncertainty about how the vote will go on election day. Alienation from established political parties and the sudden explosion of divisive issues has pushed the campaign into uncharted political waters.

In these elections, where uncertainty is the only certainty, all we can say with confidence is that a run-off election between the top two presidential candidates is highly likely and that the chances of a majority in congress are vanishingly small.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting