Dictators are known for their desire to stay in power. That is no different in the case of Nicaragua’s president Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo. Ortega regained the presidency in 2007, 17 years after losing elections against the opposition. Today he is in his fourth consecutive term and despite of liberating the country from a dictatorship during the 1970s, he has now turned to a dictator himself. After the release of 222 political prisoners in Nicaragua, Désirée Reder (German Institute for Global and Area Studies – GIGA) contextualises this event in the context of the regime’s repressive path since 2018.

Lee este artículo en español

In April 2018, the violent response towards smaller protests in Nicaragua provoked an outcry across all social groups and resulted in nationwide mobilisation. The disproportional violence against peaceful protesters was the spark that made many Nicaraguans voice their accumulated discontent. For years, Daniel Ortega has been under increasing criticism for corruption, autocratic tendencies and nepotism, especially since his wife also became Nicaragua’s vice president in 2017, and his children are in central political positions or run state-linked corporations. Furthermore, his governing included dismantling democratic institutions and processes, provoking migratory and economic crises. Soon the demands escalated towards early elections and even the resignation of President Ortega.

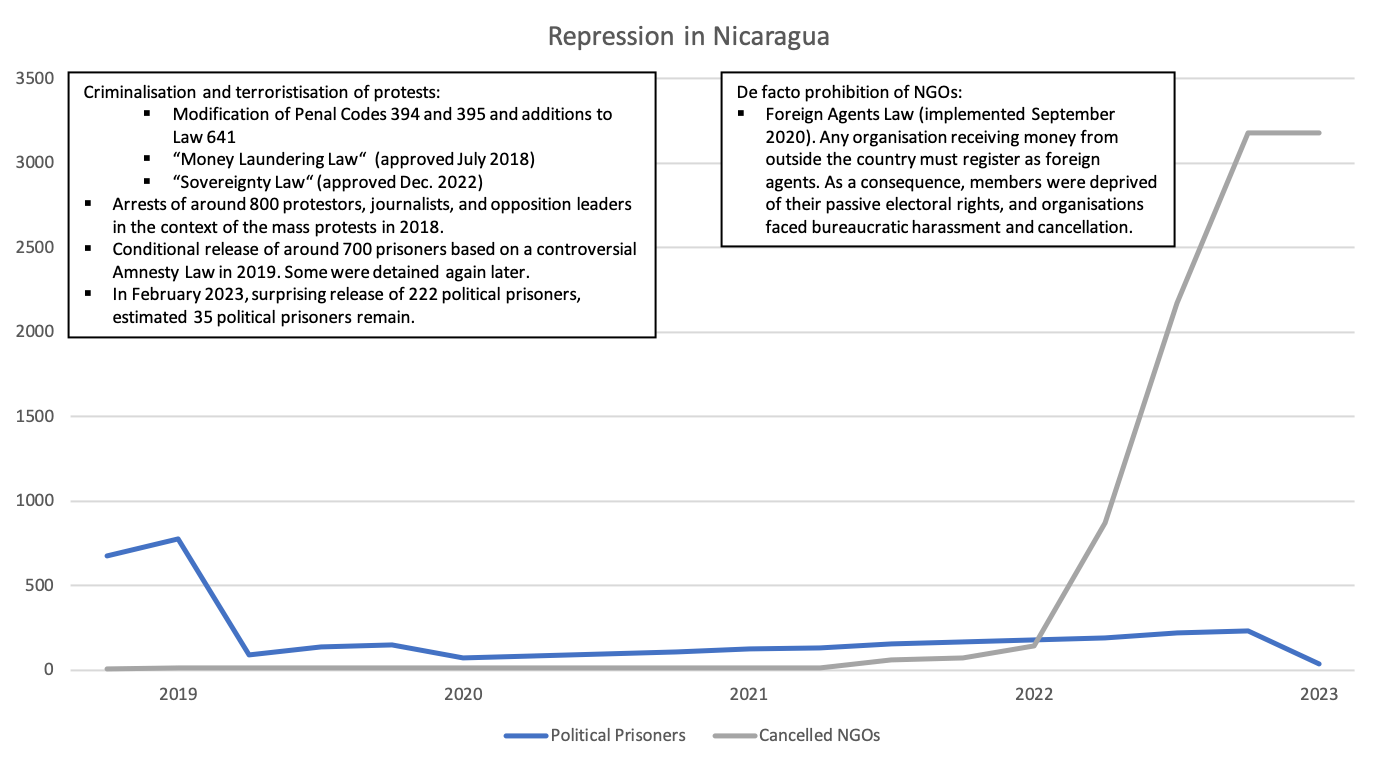

As the outlawing protests, intimidation and disproportionate violence against peaceful protesters did not have the anticipated deterring effect, the regime used repression in other ways. First, the regime focused on attacking media and journalists, eradicating the presence of an independent press in the country. Later, in the run-up for the presidential elections in 2021, they eliminated all real competition by imprisoning political opponents who were likely to run as candidates and are among the now released. What followed was electoral fraud in the presidential elections in 2021 and the municipal elections in 2022, which both had minimal voter turnout as a form of silent protest.

Criminalising freedom of expression

These steps were legalised by several laws, criminalising the freedom of expression, association, movement, and political participation. More than 50 opposition figures were either considered “traitors”, sentenced under the so-called “Sovereignty Law”, or accused of disseminating hate speech, condemned by the “Cybercrime Law.” In 2022, the regime turned towards the Universities, NGOs and Churches, further narrowing down the space for civil society. Over 12 universities were shut down, foreign diplomats who had condemned the regime’s actions were expelled, and the churches suffered around 400 state-driven attacks between 2018 and 2022. Based on the “Foreign Agents Law,” more than 3,000 licenses were cancelled, resulting in 43% of NGOs shut down by December 2022.

In February 2023, the Nicaraguan government made a surprising move: They released 222 of the more than 275 prisoners of conscience. Some had spent years in the country’s infamous prisons El Chipote and La Modelo. This step is surprising on various grounds: the Ortega regime has previously ignored calls by the international community to free the prisoners, and the incarceration of government opponents was part of the upscaling repression over the past years. So why does the release of political prisoners in Nicaragua come with a bitter aftertaste?

The release of Nicaraguan political prisoners

What might appear like a humanistic move looks quite different when taking the entire picture into consideration. The release of the political prisoners was combined with their expulsion from the country and the deprivation of their nationality. They learnt about their release and its conditions only when arriving at the airport. Two of them did not accept these terms and decided to stay in the country, although this would mean being imprisoned again. Among them was Bishop Rolando Álvarez, who was transferred to a high-security cell and sentenced to 26 years in prison the next day. The remaining were flown off to the US, which granted them humanitarian patrol. A few days later, the nationality of 94 more Nicaraguans, all outspoken critiques of Ortega and Murillo, was revoked, some of them living still in Nicaragua. The revocation of citizenship was more than a symbolic move.

All the 317 ex-patriated individuals lost their rights as Nicaraguan citizens and, hence, their assets. The authorities immediately started confiscating their pensions, properties and homes. Meanwhile, Spain and Chile were among the countries offering them citizenship.

Again, the regime did not fall short in legalising its actions. Shortly after the expulsion of the released prisoners, the co-opted National Assembly rushed through a reform of Article 21 of the Constitution to allow the revocation of the citizenship of individuals sentenced for “treason” under the “Sovereignty law.” Despite the constitutional change, the expatriation of government opponents poses an illegal act as well under international as under domestic law.

The Nicaraguan law requires changes to the constitution to be approved by two legislatures of the National Assembly. This means it becomes legal only after next year’s National Assembly confirms the act. Furthermore, they missed changing Article 20 of the constitution, which states that “no Nicaraguan can be deprived of nationality.” In summary, a not-yet-existing law was applied, which even contradicts an existing law.

A similar case applies under international law. It conflicts with the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, which Nicaragua has been party to since its accession in 2013, and runs against the international human rights standards contemplated in the American Convention of Human Rights, and the International Pact of Civil and Political Rights.

Why did the regime release the prisoners?

Jared Genser, a human rights lawyer who had defended many political prisoners, already proposed last year that dictators cannot hold political prisoners forever: “In my experience, dictators only release political prisoners when they have to. They don’t do it when they want to, but […] if it’s a choice between their survival and releasing political prisoners […].”

In fact, Nicaragua is suffering under the sanctions, and especially the inner circle of the regime has been targeted by sanctions. Research shows the country’s economy’s strong dependence on remittances sent by the Nicaraguan diaspora.

Besides, it had become public that talks had taken place between the regime and the Vatican last year. Hence, it is an obvious assumption that the prisoner’s release might be the result of some kind of negotiation.

However, both Ortega and US representatives insist that there was no dialogue but that it was Nicaragua’s unilateral decision. The harsh action against Bishop Álvarez, as well as the revocation of the nationality of additional individuals, served potentially to underline this position and demonstrate that the regime continues in control.

Scenarios for the future of Nicaragua

It is possible that the pressure posed by international sanctions and isolation had Nicaragua already at the point where it was more beneficial for them to release the prisoners than to keep them. There are some scenarios that could fit this situation. First, on previous occasions, international actors had called the Nicaraguan government to release the prisoners, and possibly, that was directly or indirectly posed as a pre-condition to negotiations which could lead to the lifting of sanctions.

Another scenario is that also within the country, the indignation over the imprisonment of many popular figures and the knowledge about their conditions had grown. By releasing and expulsing them, the regime might have seen a chance to define the narrative, framing them as US-American “mercenaries” instead of Nicaraguan citizens. In my research, I find political communication and discursive manipulation to be a central aspect of the regime’s repressive strategy. Additionally, by expelling more Nicaraguans, it might hope they build a life elsewhere and send remittances to the country.

One thing is for sure: the Ortega Murillo family wants to stay in power at any cost. For years they have tried to establish Ortega’s wife, Rosario Murillo as his successor. At the same time as announcing that hundreds of his opponents would be left stateless, Daniel Ortega declared his wife the country’s co-president. However, she lacks the backing of the party base, and it is unlikely that she will be accepted.

The future of Nicaragua remains uncertain. The events of 2018 have created division among society, adding to the persisting fragmentation from the 70s and 80s. The events from the civil war have never been processed; many taboos and grievances remain, dividing entire families. A process of truth finding, memory, reconciliation and transitional justice will be necessary for both the civil war and the times since 2018. Education will be crucial in this process, creating the understanding that transitional justice is not the same as retaliation and reconciliation cannot work with creating taboos but remembrance and compromises.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the author rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Protest in Managua, Nicaragua on August 18th 2018 / Will Ullmo (Shutterstock)