Colombia’s pathbreaking presidential election of 2018 will most likely be won by Álvaro Uribe’s protege Iván Duque, which could endanger the peace process and signal a return to a dark past of violence and exclusion. But support for leftist and centrist candidates Gustavo Petro and Sergio Fajardo, as well as the unpredictable role of Germán Vargas Lleras, mean that this is far from a foregone conclusion, writes Tobias Franz (Universidad de los Andes).

Colombia’s pathbreaking presidential election of 2018 will most likely be won by Álvaro Uribe’s protege Iván Duque, which could endanger the peace process and signal a return to a dark past of violence and exclusion. But support for leftist and centrist candidates Gustavo Petro and Sergio Fajardo, as well as the unpredictable role of Germán Vargas Lleras, mean that this is far from a foregone conclusion, writes Tobias Franz (Universidad de los Andes).

On Sunday 27 May 2018, Colombians go to the polls for yet another important vote: the 2018 presidential elections.

Despite advances in implementing the historic peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the transition towards a post-conflict society and the achievement of a lasting peace is far from over. Much depends on the outcome of this election.

On the one hand, powerful factions of the political class that benefit from continued violence, along with certain segments of wider society, oppose the peace agreement. On the other, NGOs, political parties, and social leaders mobilise to push for peace, justice, and reconciliation. The country remains highly divided and the political situation toxic.

Five key presidential candidates are fighting it out in this challenging context, each with a different vision for Colombia’s future. Though none of them is likely to achieve an absolute majority and win in the first round, this is a crucial test of forces and an important signal for the decisive second round on 17 June 2018.

The uribista candidate: Iván Duque

Leading the polls since the Parliamentary elections is the far-right candidate Ivan Duque of the Democratic Centre (right).

Since beginning his political career in the Senate in 2014, Duque has been a close ally of former president Álvaro Uribe, whose two terms between 2002 and 2010 mean he is barred from running again.

While Duque’s eloquent discourse seems restrained when compared to Uribe’s full-frontal attacks, his proposed revision of the peace agreement, increased military spending, and reformation of paramilitary forces recall Colombia’s dark past of violence, massacres, and exclusion.

A recent investigation published by The Guardian found that the so-called ‘false positives’ scandal during the Uribe years saw over 10,000 extrajudicial killings of peasant farmers, which is three times more than was previously assumed. And just weeks ago, a key witness in a Supreme Court case against Uribe was also assassinated in broad daylight in the streets of Medellin.

Uribe is eager to use Duque to regain access to power after eight years on the sidelines under the Santos administration. Besides his business interests in keeping the war and the drug economy alive, Uribe also aims to avenge several slights against him: amongst others his perceived betrayal by Santos beyond 2010, the kidnapping and killing of his father by the FARC, the prying of the “lying” and “terrorist” media, and Colombia’s softened foreign-policy stance towards Venezuela.

In the March 2018 parliamentary elections, Uribe flexed his muscles and showed that he remains not only the most popular politician but also the most powerful man in Colombia.

He controls the largest faction in both houses, has a large army of paramilitary troops at his disposal, and has built an economic empire through large land holdings, diversified conglomerates, cattle farming, and other more dubious businesses. And he is willing to use his power to influence the elections by any means necessary.

Thus, despite being linked via Uribe to various scandals, Duque’s chances of winning the largest vote share in the first round on Sunday are high. Uribe’s popularity amongst poorer segments of society, in much of rural Colombia, in his hometown of Medellín, and amongst the elderly is likely to take Duque into the second round.

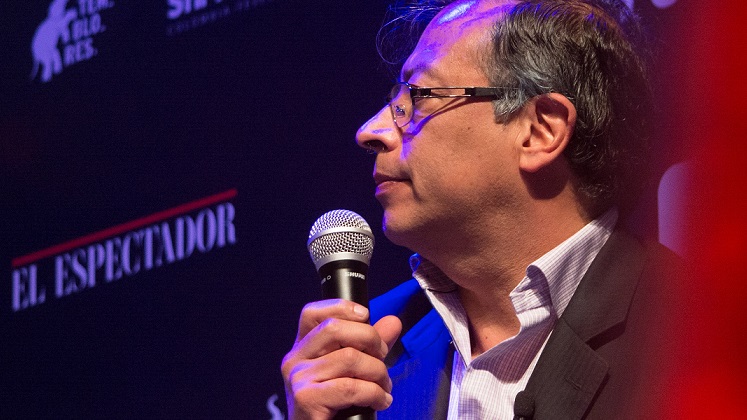

The former guerrilla: Gustavo Petro

According to recent polls, the leftist Gustavo Petro (right) will be Duque’s rival in the second round.

As a former guerrilla fighter with the M-19 Movement, Petro’s chances of securing a significant amount of the vote seemed slim at the beginning of the campaign. But the former Mayor of Bogotá has increased in popularity nationwide, and he is now the most likely runner-up.

Despite the fact that scaremongering about the communist threat still influences around 68% of the population, Petro’s “Humane Colombia” proposal to establish a twentieth-century-style welfare state has been well-received across Colombian society, but particularly amongst the young, the educated, and the poorer population of Colombia’s Caribbean and Pacific coasts.

Broadly speaking, Petro has managed to spark hope amongst progressive voters, drawing large crowds to his campaign speeches.

His programme directly challenges the dominant class interests that aim to keep society unequal, maintain low-wage comparative advantages, and press ahead with the country’s current neoliberal-extractivist economic model.

This challenge, combined with accusations of being a “Castro-Chavista” due to his admiration for Venezuela’s former president Hugo Chávez, could prevent him from reaching the second round. His stubbornness and ego could also undermine his popularity.

A potential Petro victory would further polarise an already fragmented nation. Many see him as divisive, someone who acts out of spite and anger, always blaming the “evil elite”.

He recently suggested that there will be electoral fraud to keep him out, which dangerously undermines Colombia’s democratic institutions. This in turn pushes voters towards the centre, where they find Sergio Fajardo.

The centrist outsiders: Fajardo, Vargas Lleras, and de la Calle

Fajardo (right), the former governor of Antioquia and former mayor of Medellin, does everything possible to project himself as a man of the people, the real alternative, acting neither out of vengeance nor spite.

His frequent changes of opinion, however, make it difficult to pinpoint his position and situate him on the political spectrum.

That said, his reluctance to challenge Colombia’s current neoliberal economic model, based on low-productivity and extractivist growth, suggests an alignment with the middle and upper classes, which is indeed where he finds much support.

Fajardo’s recent polling numbers surged significantly, which could help him surpass Petro to secure a spot in the second round.

Another candidate who should not be underestimated is the centre-right pick Germán Vargas Lleras (right). Despite the fact that his polling numbers are quite low at 6.6%, he controls much of the electoral “machine”: that is, local and regional political networks that mobilise voters, often through offering small monetary rewards or free lunches in exchange for votes.

Many of these voters are not captured by national polls, thereby making it hard to predict Vargas Lleras’ potential “support”.

When Vargas Lleras ran in the 2010 elections, he polled last throughout the entire campaign, but his close ties to this political “machine” ultimately lifted him into third place, close behind President Santos and Antanas Mockus.

He used his years as vice-president between 2014 and 2017 to expand this clientelist political network. A surprise surge on election day would therefore not be so surprising.

Finally, there is the forgotten fifth candidate: Santos’ chief peace negotiator Humberto de la Calle (Liberal Party). In many ways he represents the most rational choice in these highly divisive times, but de la Calle’s campaign never really took off. Instead of hoping for an actual victory on Sunday he seems to be looking forward to election night so that this “candidacy he never wanted” will finally come to an end.

High stakes in a pathbreaking election

The outcome of the 2018 presidential elections will be pathbreaking for Colombia’s future.

The country’s fragile peace is already under threat, as paramilitary groups and drug cartels have used the power vacuum left behind by the demobilised FARC to expand their operations.

Since the signing of the peace agreement 282 social leaders have been assassinated. The total number of homicides has increased by 7.2 per cent, amounting to 3491 killings since the beginning of the year.

The threat exists that instead of embracing a peaceful future, Colombians may elect the demons of the past with potentially disastrous outcomes: paramilitary violence could yet again be legitimised, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) substantially shortened, the budget for reconciliation slashed.

With a hardliner as President, relations with Venezuela and Ecuador could either cool to freezing or heat up to the point of military confrontation as in 2008, which would have devastating consequences for the stability of the region.

However, fears of another disappointing election night like the 2016 referendum are balanced by the hope that the country can finally turn the corner and leave behind its violent history.

While the election will most likely result in a close victory for Iván Duque, the combined share of the progressive and moderate vote is likely to be higher, meaning the far-right could yet be defeated in the second round on 17 June.

But for that to happen, political actors, organisations, and movements campaigning for a continued commitment to peace will have to overcome fragmentation and build joint support for a single, unifying candidate.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting