Despite airlines’ push to divert travellers towards buying tickets via their own websites, online travel agents still play a very important role. In 2011, American Airlines introduced its own booking system for travel agents, prompting a backlash from traditional distributors who blocked access to their platforms. Volodymyr Bilotkach, Nicholas Rupp and Vivek Pai take a close look at the case, finding that the loss of access cost American Airlines more than $50 million in revenue through reduced ticket sales. They write that such conflicts between airlines and traditional channels may become more common in the future, as airlines continue to try to unbundle their services.

Despite airlines’ push to divert travellers towards buying tickets via their own websites, online travel agents still play a very important role. In 2011, American Airlines introduced its own booking system for travel agents, prompting a backlash from traditional distributors who blocked access to their platforms. Volodymyr Bilotkach, Nicholas Rupp and Vivek Pai take a close look at the case, finding that the loss of access cost American Airlines more than $50 million in revenue through reduced ticket sales. They write that such conflicts between airlines and traditional channels may become more common in the future, as airlines continue to try to unbundle their services.

The Internet has drastically changed the airline ticket distribution industry throughout the world. While most major airlines are trying their best to divert as many consumers to their web-sites as possible; online travel agents still play very important role in this business. The fight for passengers between the ticket distribution channels is quietly happening behind the scenes, but sometimes the battles of that war become all too visible. Three years ago, a conflict between a major US airline (American Airlines) and several key ticket distribution agents (online travel agents Expedia and Orbitz) resulted in the air carrier losing access to these important distribution platforms. In addition, Sabre – one of the key Global Distribution Systems – briefly introduced a display bias against American Airlines. This conflict allowed us to estimate that the loss of access to the Expedia/Orbitz platforms resulted in an over $50 million reduction in revenue for American Airlines

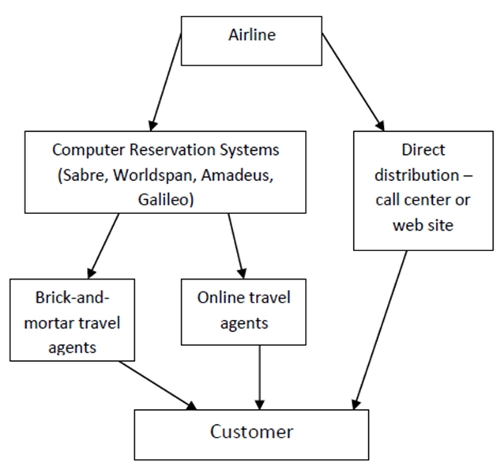

When you make a request for travel options with an online travel agent, this agent accesses the airlines’ inventories via a Global Distribution System (GDS). These systems are also known as the Computer Reservation Systems (CRS), as Figure 1 illustrates. There are four major players on this concentrated market. About five years ago, American Airlines started approaching the travel agents, marketing to them its own “AA Direct Connect” platform, which would allow the agents to access the carrier’s inventory bypassing the GDS platforms. AA Direct Connect was offering additional functionality not available via the traditional distribution channels – such as the ability to book add-on services, including checked luggage and in-flight meals. Such a move prompted a backlash from the traditional distributors, who have blocked the carrier’s access to their platforms.

Figure 1 – Airline ticket distribution

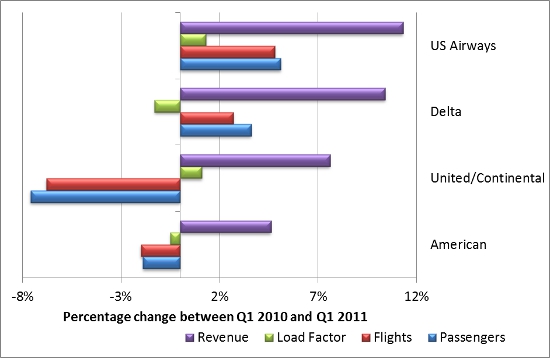

During the first quarter of 2011, American Airlines was unable to sell its tickets via several major online travel agents, which reduced its revenues, load factors, passengers, and numbers of flights, as compared to some its close competitors, as Figure 2 illustrates. Given the structure of the ticket distribution industry, we initially suspected that the conflict has put at least $200 million (or 6 percent) of the airline’s revenue at risk during the first quarter of 2011.

Figure 2- Percentage change in Results of American Airlines and Main Competitors (US Domestic Market)

Note: The substantial decline in passenger numbers and flights reported by United/Continental is likely related to their merger (completed in October 2010).

Having analysed the price data for the first quarter of 2010 and 2011, we have reached the following conclusions. First during the conflict time American Airlines’ fares were 2.7-4.2 percent lower than what it would have charged otherwise. Second, the effect is only visible in one-stop itineraries, and not in nonstop ones. We have a simple explanation for this disparity: travellers are well aware of airlines’ non-stop services, so even if these fares are not available for purchase via a travel agent, the passengers are able to purchase these tickets elsewhere (e.g., on the airline’s website). This is less likely to be the case for one-stop itineraries, however. Our third finding is that the conflict with the travel agencies did not appreciably affect the number of tickets that the airline sold during the first quarter of 2011. Finally, we estimate that during the first quarter of 2011 the loss of access to several important online distribution platforms resulted in over $50 million reduction in revenue for the airline.

In April 2011 American Airlines filed a lawsuit alleging that Expedia, Orbitz, and Sabre conspired to restrict access to their ticketing platforms in retaliation for the American’s marketing a competing ticket delivery platform for travel agents, designed to bypass the existing global ticket distribution systems and connect their systems directly with American servers. The case was settled out of court. The exact amount of compensation American Airlines received from this settlement has not been disclosed, but American fourth-quarter [2012] earnings statement did report a $280 million of revenue from settlement of a commercial dispute. This value is substantially higher than our estimate of the conflict’s impact on American’s revenue. Yet, we should note that our research only covered the first quarter of 2011, whereas American Airlines’ fares remained unavailable via Orbitz for several more months. Further, it is difficult to evaluate when and how any potential display bias by Sabre could have affected the airline.

In addition, American did not sit idle when their tickets were dropped from the existing distribution platforms, as they took multiple steps to mitigate the potential impact of the dispute on its revenue. During the first quarter of 2011, American initiated several marketing/advertising campaigns to reach its customers and drive traffic to their web site. These include the February 2011 launch of Facebook and Twitter channels, which provided followers with opportunities to earn additional miles and receive notification of American fare promotions. In March 2011 American offered a million frequent flier miles sweepstakes to customers who watch a testimonial video that promotes the AA.com web site for booking tickets. American also offered incentives (free tickets) for small/medium size California businesses that increased the number of tickets booked through AA.com. It is possible that the cost of these marketing campaigns could have been added to the settlement.

The conflict we studied in our research is potentially a sign of changes to come in the US travel services distribution industry. As the airlines are working to unbundle their services (charging for seat reservations, checked luggage, etc.) they are finding the traditional distribution channels inadequate for their needs. Yet, the carriers’ attempts to create their own distribution platforms are meeting rather stiff resistance from the dominant market players, who are naturally interested in preserving the status quo. We foresee some potentially interesting developments in this industry over the next several years, with respect to both strategies employed by the airlines and travel agents, and potential antitrust litigation.

This article is based on the paper ‘Value of a Platform to a Seller: Case of American Airlines and Online Travel Agencies’.

Featured image credit: Andrew Morell (Creative Commons BY ND)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/T2K4x9

_________________________________

Volodymyr Bilotkach – Newcastle University

Volodymyr Bilotkach – Newcastle University

Volodymyr Bilotkach is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at Newcastle University Business School. His research interest spans the aviation sector of economy. He has published extensively on airline alliances, and written on issues ranging from airline mergers to airport regulation to economics of distribution of airline tickets.

_

Nicholas G. Rupp – East Carolina University

Nicholas G. Rupp – East Carolina University

Nicholas G. Rupp is an Associate Professor of Economics at East Carolina University. His primary research areas are industrial organization, financial economics, and economics of crime.

Vivek Pai – University of California, Irvine

Vivek Pai – University of California, Irvine

Vivek Pai is a research associate at the Center of Economics and Public Policy at the University of California, Irvine. He has researched extensively on the economics of networks, specifically in the context of airlines. His work has appeared in the in Industrial Journal of Industrial Organization, Journal of Air Transport Management, and Transportation Science. He holds a bachelors in economics from Cornell University, a masters in operations research from Columbia University, and a doctorate in economics from the University of California, Irvine.