In the American states, campaign finance laws require disclosure of private information for contributors at relatively low thresholds ranging from $1 to $300. The Internet has made it relatively easy to publicize such information in a way that changes the social context for political participation. Ray La Raja looks at how public disclosure of campaign contributions affects citizens’ willingness to give money to candidates. Drawing on social influence theory, his analysis suggests that citizens are sensitive to divulging private information, especially those who are surrounded by people with different political views. He shows that individuals refrain from making small campaign contributions or reduce their donations to avoid disclosing their identities.

In the American states, campaign finance laws require disclosure of private information for contributors at relatively low thresholds ranging from $1 to $300. The Internet has made it relatively easy to publicize such information in a way that changes the social context for political participation. Ray La Raja looks at how public disclosure of campaign contributions affects citizens’ willingness to give money to candidates. Drawing on social influence theory, his analysis suggests that citizens are sensitive to divulging private information, especially those who are surrounded by people with different political views. He shows that individuals refrain from making small campaign contributions or reduce their donations to avoid disclosing their identities.

Citizens strongly favor disclosing the source of political contributions to parties and candidates. Aside from serving as deterrent to corruption, making donations transparent provides information to voters to hold politicians accountable. For decades many American states have required donors to disclose information about themselves—names, addresses, and even occupations. Today, this information is accessible via the Internet for all to see. In recent research, I explore the potential negative consequences of disclosure based on theories of social influence, which suggest that revealing political references imposes real costs on some people.

The salience of these costs was made apparent to me when I read about what happened to petition signers and donors in a controversial California ballot measure against same-sex marriage. The ballot measure won, and opponents used a mash-up of donor lists and Google maps to pinpoint the homes and businesses of supporters. In the aftermath of the election, the news media reported acts of intimidation, vandalism, boycotts and even death threats toward citizens who apparently supported the ballot measure.

Perhaps this was an unusual case but it raises important issues about the role of transparency in civic life. Notable figures in the US, such as Justice Antonin Scalia, favor a lot of transparency, arguing that citizens should be responsible for what they say or do. In his words, “running a democracy takes a certain about of civic courage”. Others claim this position is too heroic for ordinary citizens and will surely discourage political participation. My goal was to test empirically whether citizens participate less when they realize that private information will be divulged to the public. I looked specifically at how such laws affect small donors.

Using experimental survey data I looked at how potential donors behave when they realize their names might be made public. Half the respondents were asked “how much, if anything, would you consider donating to a candidate who reflects your views: The amounts offered were between 0-$2500 and most respondents (who chose to donate anything) gave amounts less than $50. In the treatment group respondents had the same question but with a the additional statement: “please note: names of donors are made public on the Internet.” I also varied this last statement to adjust the amounts at which donations would be made public (e.g., “over $50” or “over $100”) to see if people changed the amounts they gave based on these thresholds.

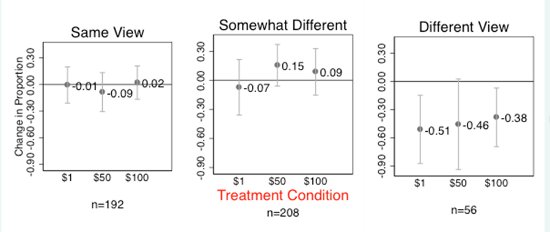

The findings demonstrate that transparency does, in fact, have a chilling effect on participation. And the impact is especially salient for citizens who are cross-pressured. The far right box below shows respondents with ‘‘very different’’ views from those around them (who would be able to know of their donation). The horizontal line across the graphs signifies a baseline of zero for the control condition (no disclosure statement), and the point estimates reflect deviations from this baseline. Those who face disclosure starting at $1 experience a 51 percent decline in the proportion donating compared to the control; at $50 disclosure the decline is 46 percent; and at $100 the decline is 38 percent.

Figure 1 – Social Context and the Effect of Publicity on Proportion Contributing

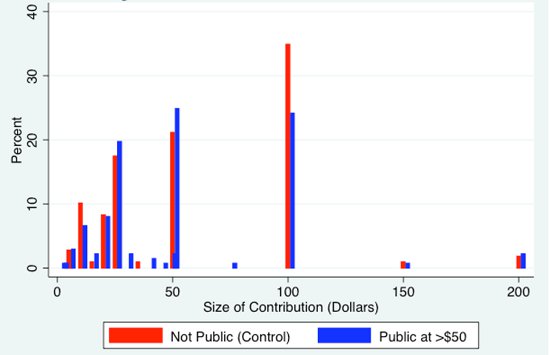

The findings also show that citizens are more likely to give contributions below the threshold when they learn the donation will be revealed. The bar chart below illustrates the contributions from respondents in the disclosure group (blue) and non-disclosed group (red). Donors typically give sums in round amounts like $25, $50, and $100. However, donors faced with a $50 disclosure threshold are less likely to make a $100 donation compared to thecontrol group with no disclosure threshold. Many choose instead to bunch theircontributions at $50 or $25 to avoid disclosure. The graph does not show this but the $50 threshold causes donors to cut back on contributions from an average size of $80 to just $32, which reflects a 60 percent decrease.

Figure 2 – Distribution of Small Contributions When Disclosure Threshold at $50

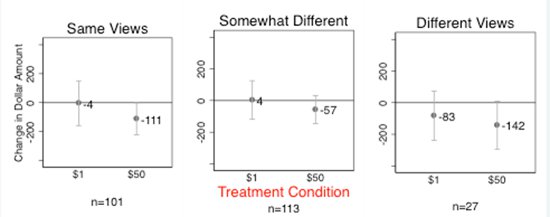

Finally, I look more closely at the cross-pressured citizens. Their giving declines even more steeply than other citizens. The figure below shows that citizens react negatively but those surrounded by people with ‘different views’ change their behavior the most when facing disclosure at $50 threshold. The average contribution plummets by $142 (from a baseline of $175) among respondents facing strong interpersonal cross pressures. This brings the average contribution to just $33, which is a decline of 81 percent.

Figure 3 – Social Context and Effect of Publicity on Amount Contributed

In sum, it appears that citizens do not necessarily like to reveal preferences, particularly those who experience interpersonal cross-pressures. The analysis adds to our understanding about how secrecy or its absence affects citizens’ willingness to engage in politics. Importantly, this study suggests that the Internet may change the social context for some forms of political engagement in potentially negative ways, even as it enables some citizens to engage more robustly (very likely those with strong political views who surround themselves with like-minded partisans).

Overall, the findings indicate that transparency is not costless. Policymakers should think about trade-offs and where transparency is most usefully applied. With respect to political contributions it might make sense to focus on big donors and devise ways to provide partial but meaningful disclosure to voters without divulging individual private information.

This article is based on the paper ‘Political Participation and Civic Courage: The Negative Effect of Transparency on Making Small Campaign Contributions’ in Political Behavior.

Featured image credit: David (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1wphcg9

_________________________________

Ray La Raja – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Ray La Raja – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Ray La Raja is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science and associate director of the UMass Poll. He is author of Small Change: Money, Political Parties and Campaign Finance Reform (U. Michigan Press 2008) and editor of New Directions in American Politics (Routledge, 2013). He is founding editor of The Forum, an electronic journal of applied research in American politics.

5 Comments