Despite the slowdown in incarceration rates that has occurred in recent years, more than one child in every 50 has a parent in prison in the U.S. today. In new research that samples more than 12,000 children and young adults, Lauren C. Porter and Ryan D. King find that children whose father was incarcerated were likely to have a level of violent or destructive crime 23 percent greater than their peers.

Despite the slowdown in incarceration rates that has occurred in recent years, more than one child in every 50 has a parent in prison in the U.S. today. In new research that samples more than 12,000 children and young adults, Lauren C. Porter and Ryan D. King find that children whose father was incarcerated were likely to have a level of violent or destructive crime 23 percent greater than their peers.

American criminal justice policy seems to be at a crossroads. After nearly four decades of more bars, more guards, more cops, and political posturing about crime and punishment, the discourse and indeed the policies are changing. In November, Californians voted to reclassify several felonies as misdemeanors, conservative groups such as Right on Crime are spearheading reform that would have been labeled ‘liberal’ a mere decade ago, and the incarceration rate has been declining.

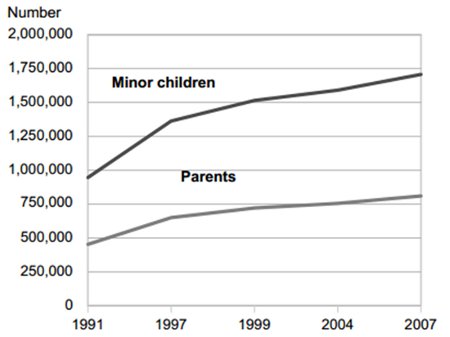

Embedded in the conversation about reform is the significant impact that imprisonment has on inmates beyond their stint of incarceration. Felons in the United States typically lose the right to vote for a period of time, they are ineligible for certain types of employment, and many suffer from stress-related health problems. Further, these collateral consequences might spill over to affect another, less vilified group – their kids. As Figure 1 shows, the number of children with a parent incarcerated in the U.S. is measured in the hundreds of thousands, and today about 2.3 percent of all children in the United States have a parent in prison.

Past research suggests that losing a parent for even a short period of time may be traumatic, confusing, or in some cases, beneficial for children. We thus investigated a seemingly straightforward question: are children who had a father incarcerated at a higher risk of getting involved in crime? We find that paternal incarceration does lead to higher crime rates among their children – especially in the case of violent or destructive crime.

Figure 1 – Estimated number of parents in state and federal prisons and their minor children

Source: U.S. Department of Justice

There are different schools of thought on the expected relationship between a father’s incarceration and child delinquency. On the one hand, children of incarcerated fathers might be at an elevated risk of criminal behavior. An absent father reduces supervision, severs the father-child bond, and could be a major stressor in a child’s life. Criminologists have shown that each of these factors is associated with crime and violence. On the other hand, most people going to prison committed at least one crime, and about half of state and federal prisoners are in for violent offenses. Perhaps criminally active fathers are a bad influence, and it follows that removing the father could actually protect the child. A third option is that having a father in prison simply doesn’t matter. Imprisonment is generally coupled with a host of other factors associated with children’s delinquency, including poverty, living in a tough neighborhood, family turmoil, and exposure to violence. Prison may simply be one item on a long list of risk factors – but it may not affect children above and beyond these other obstacles.

This latter point about imprisonment clustering with a crowd of other adverse life circumstances creates a challenge for researchers trying to pin down the influence of paternal incarceration. We find ourselves confronted with the usual rat’s nest of correlated variables, and even if we could measure them all on a survey it would prove tricky to isolate the impact of a singular variable. For obvious reasons we can’t randomly assign some children to an incarcerated father. What we needed was a good comparison group – a group of kids who we could presume share many of the same background characteristics as kids with an incarcerated father, except of course for the incarceration part. Our solution was deceptively simple. What if we compare children with an incarcerated father to children who will have an incarcerated father? That would seem to be an ideal comparison group, but how would we know which juveniles are on the verge of having a father imprisoned?

We found our opportunity with the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health and its sample of over 12,000 children and young adults. This survey began in adolescence and continued as the group moved into adulthood. At the very first wave of interviewing when respondents were between 11-21 years old, each was asked about their delinquent behavior. These same respondents were re-interviewed multiple times over the next thirteen years, and among the battery of questions were some that asked about their father’s history of incarceration. We could thus establish whether and when a respondent’s father was incarcerated, and this enabled us to create two groups of adolescents for comparison – one consisting of those who experienced a father’s incarceration prior to being asked about their involvement in crime, and a second group who had a father incarcerated soon thereafter.

We started by looking at property crime and did a generic comparison of children with previously incarcerated fathers and children who haven’t, and perhaps never will, have a father in prison. In line with intuition, children were more criminally active if their fathers were ever locked up. But once we changed the comparison group to children who will in the future have a father incarcerated, the correlation disappeared.

However, this was not the case with violent and destructive behavior. This correlation persisted, even when using our strategic comparison group. Children who experienced the incarceration of a father had an expected level of crime that was 23 percent higher than their comparable peers. We concluded that having a father incarcerated is an emotional event in the lives of children that leads them to act out in violent and destructive ways. We also found that the bond between father and child was weakened by the bout of incarceration, helping to explain these outcomes.

Our findings about violent and destructive behavior align with other research which shows that children of incarcerated parents are worse-off on many of dimensions, including academic performance, health, and delinquency. What we now need to determine is how far reaching and long lasting the effects of having a father incarcerated truly are. In their book Children of the Prison Boom, our colleagues Sara Wakefield and Chris Wildeman suggest that parental incarceration could perpetuate inequality. Perhaps it’s time that the impact of prison on families gets bound up with the discussion of crime as the U.S. reforms its policies and practices in the realm of criminal justice.

This article is based on the paper ‘Absent Fathers or Absent Variables? A New Look at Paternal Incarceration and Delinquency’, in the Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Neil Conway (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1I0HBYP

_________________________________

Lauren C. Porter – University of Maryland

Lauren C. Porter – University of Maryland

Lauren Porter is an Assistant Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Maryland. She is largely interested in topics that revolve around punishment. In particular, she investigates questions related to incarceration, including the collateral consequences of imprisonment and how population dynamics shape incarceration trends. Her current work also explores how offenders interact with neighborhood environments to choose crime locations and targets.

Ryan D. King – The Ohio State University

Ryan D. King – The Ohio State University

Ryan King is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at The Ohio State University. His research interests are in criminology, law and society, criminal punishment, and intergroup conflict, with secondary lines of work focusing on the life course and anti-Semitism. Current research projects investigate the causes of hate crime, the effects of parental incarceration on child wellbeing, the criminal sentencing and deportation of non-citizens, the relationship between hate crime and terrorism, and the association between skin hue and criminal sentencing.