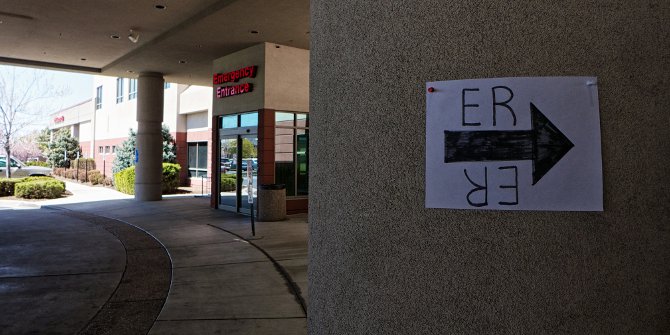

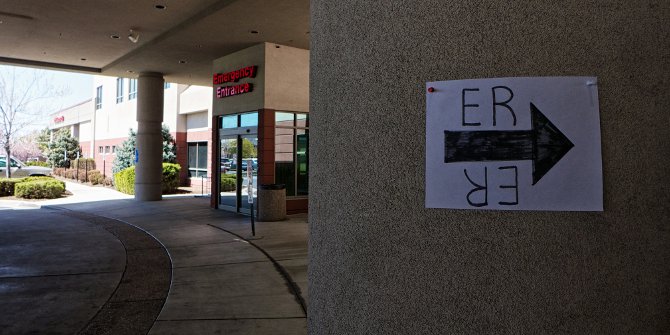

A lack of resources to treat all incoming patients is a longstanding and seemingly intractable problem faced by hospital emergency rooms across the country. But how do health professionals triage incoming patients to decide who gets care and who does not? In a new ethnographic study of hospital admissions, Armando Lara-Millan finds that hospital staffs tend to invoke criminal stigma to deny care to those that fit certain ‘criminal’ profiles, while police patrols encourage those who are concerned about arrest to leave. He contrasts these practices with the prioritization of inmates and arrestees who are given beds regardless of the severity of their conditions.

A lack of resources to treat all incoming patients is a longstanding and seemingly intractable problem faced by hospital emergency rooms across the country. But how do health professionals triage incoming patients to decide who gets care and who does not? In a new ethnographic study of hospital admissions, Armando Lara-Millan finds that hospital staffs tend to invoke criminal stigma to deny care to those that fit certain ‘criminal’ profiles, while police patrols encourage those who are concerned about arrest to leave. He contrasts these practices with the prioritization of inmates and arrestees who are given beds regardless of the severity of their conditions.

Much has been written about the remarkable increase in incarceration rates, intensification of policing, and proliferation of crime control language in major public institutions within the United States. In recent research, I delve deep into the medical decision-making of one America’s most overcrowded public emergency rooms and find a surprising development. The heavy policing, criminal suspicion, and high incarceration rates now ubiquitous in American cities have become infused in medical language and determinations of who is fit for admission.

My research is the first to document a paradoxical finding: the conferral of medical resources to inmates and arrestees is organizationally linked to the denial of medical resources to the general, non-incarcerated urban poor. That is, that general patients, those who have little relationship to the criminal justice system, are subject to criminal suspicion, policing, and reduced access, while, conversely, inmates and arrestees are prioritized and rushed admission.

Utilizing ethnographic methods and a count of hospital admission decisions, I examine closely how medical triage and diagnosis unfolds in real-time: medical professionals face an impossible choice, with so few beds available and so many medically qualified patients; they must find some way to favor some patients over others. In today’s heavily policed cities, it is criminal justice and criminal suspicion that provides an efficient rubric. This careful analysis shows clearly how legal and criminal justice logic slowly evolve and matriculate into health diagnosis and come to be rationally linked among professionals with the best of intentions.

One of the initial ways in which criminal stigma is assigned to general waiting patients is through the widespread administration of pain medication. Nurses develop a baseline understanding that patients seek emergency room care to access these opiates, and their denial of such patients is viewed as a kind of crime control. This baseline understanding is useful in reconciling the most pertinent organizational conundrum faced by triage staff: there are many more patients who qualify for admission than can be accommodated by the ER. When faced with such a conundrum and unable to find valid medical reasons to favor one qualified patient over another, medical staff invoke criminal stigma to make final admission decisions.

Second, regarding policing, official police patrol the front room waiting lobby, which decreases access to health care resources for the non-incarcerated urban poor. While police periodically run background checks on waiting patients, which pressures patients with arrestable statuses to leave the ER early, police also participate in vital-signs reassessment, which ends up expelling patients who have no official contact with the criminal justice system. While a seemingly inappropriate practice, without these systematic police patrols the emergency department would have little way to diffuse its immense general patient waiting list.

Finally, incarceration affects health care access when a nontrivial number of inmates and arrestees are prioritized for beds, regardless of the severity of their ailments. This practice results in a loss of beds for more medically serious general patients. In other words, if the urban poor happen to be wards of the criminal justice system, they receive rushed health care resources, but if they enter health care organizations on their own accord they are policed, delayed, and deterred from accessing care. Triage staff simultaneously decries the loss of beds – which adds to their difficulty in admitting patients from the front room – and accept public safety arrivals out of professional courtesy.

Ultimately, I have unraveled an important “black box” within the contemporary study of mass imprisonment and its effects on population health in the United States: demographic studies have shown that a proportion of black men incarcerated experience some health benefits compared to their peers outside of prison. Specifically, compared to their peers outside of prison, some cohorts of black men are less likely to die while in prison. Patterson (2010) hypothesizes that while the protective effects of imprisonment – protection from homicide or car accidents – explain some of incarceration’s effect on mortality; it is mandated in-custody health care that may be driving some incarcerations’ positive effect on health. The organizational dynamics I uncover suggest that, in fact, it is rational decision-making in public health care organizations that explain some of this wider demographic trend. In other words, a comprehensive analysis of healthcare for the urban poor in the United States is incomplete without reference to the dynamics I have described.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Public Emergency Room Overcrowding in the Era of Mass Imprisonment’, in the American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ABD6gN

_____________________________________

Armando Lara-Millan – UC-Berkeley

Armando Lara-Millan – UC-Berkeley

Armando Lara-Millan is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at UC-Berkeley. He is is an ethnographer and historical sociologist. His research interests are in the fields of health, mass imprisonment, and political sociology. He is completing a book manuscript on how overwhelmed public institutions like public hospitals and county jails are able to, despite disastrous underfunding, provide services to large numbers of people and create an illusion of policy success.