More than in any election in the past decade, Donald Trump was able to use Twitter as a means of reaching out to his core constituency. But how do other politicians take advantage of this new way of communicating? In new research, Leticia Bode analyzed over 10,000 tweets and nearly 1,000 television ads from the 2010 Senate elections. She finds that compared to traditional ads, Twitter is not constrained by a predetermined campaign message strategy and can be easily adapted to respond to new information in real time.

More than in any election in the past decade, Donald Trump was able to use Twitter as a means of reaching out to his core constituency. But how do other politicians take advantage of this new way of communicating? In new research, Leticia Bode analyzed over 10,000 tweets and nearly 1,000 television ads from the 2010 Senate elections. She finds that compared to traditional ads, Twitter is not constrained by a predetermined campaign message strategy and can be easily adapted to respond to new information in real time.

The president-elect loves Twitter. While he has certainly used the medium differently than other politicians, candidates and elected officials at all levels have embraced Twitter as a means of reaching constituents and potential voters. Since Twitter launched in 2006, there has been a relatively fast adoption of the platform by politicians the world over. But how do they use it? Is Twitter an extension of their broader campaign strategy or message? Or does it represent something new and fundamentally different.

These questions led my collaborators and I to compare an old campaign messaging platform – broadcast television advertisements – to a new platform – candidate tweets. We were interested in how message lined up across these two platforms, in terms of 1) volume, 2) policy issues, and 3) tone.

How we studied this

Because most attention to political elite use of Twitter is concentrated at the presidential level, we decided to observe the use of Twitter and ads among those running for the Senate, and we focus on the 2010 election. After eliminating those candidates who did not have a Twitter account (four candidates), we created a sample of 73 candidates for Senate in 37 races.

Over the course of the 2010 election, we archived all 10,303 tweets posted by accounts associated with these Senate candidates, and coded them for tone and issue content. Our unit of observation is a single tweet. Candidates ranged in tweet frequency from 0 per day to a high of 76, with a mean of about 4 tweets.

These data were paired with Wesleyan Media Project data on 961 unique ads aired on television 576,933 times by these same candidates (and coded the same way) during the course of the campaign. The unit of observation for these data is the ad airing. Candidates ranged in airing frequency from 0 to 878 per day, with a mean of 143 ads.

Volume

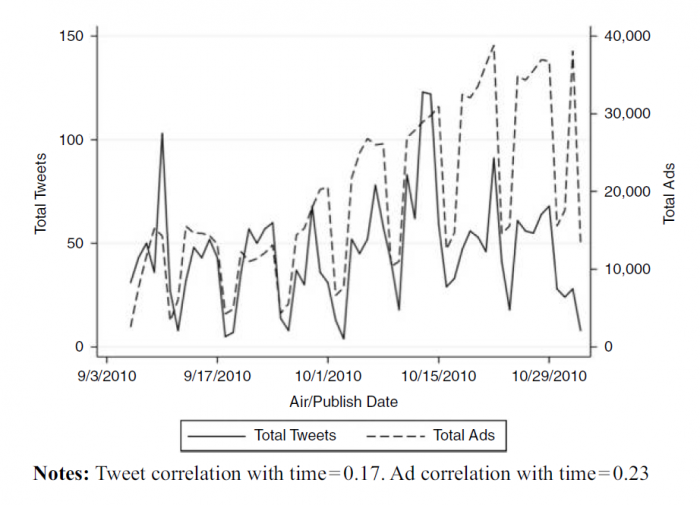

Overall, tweets and ads follow a similar pattern over the course of the election. As can be seen in the figure below, both are cyclical in terms of each week – the vast majority of ads are aired during the week, and most tweets are also put out on weekdays.

And both forms of campaign communication generally increase over the course of the campaign, as Election Day draws closer. However, in the final weeks of the campaign, ads continue to increase while tweets drop off. We attribute this to allocation of resources – whoever is in charge of the campaign Twitter account likely also has other duties that occupy them in the final weeks of the campaign. It is worth noting that this is likely something that has changed over time, as campaigns have devoted greater resources to new media like Twitter.

Figure 1 – Total Ads and Total Tweets by Day

Issues

This is one area where the descriptive statistics are quite illuminating. While only 5.9 percent of ad airings have absolutely no issue content, 54.2 percent of tweets have no issue content, suggesting that issue mentions are much less prevalent on Twitter. This is an indication that candidates may be using Twitter in a fundamentally different way than they use traditional campaign tools.

Correlations between issue mentions in ads and on Twitter by candidate are quite low, reaching only as high as 0.13 for social welfare issues (this includes health care, which might explain why it is higher than other issues, given that health care was a major issue in the 2010 election), and reaching significance in only three (law and order, environment/energy, and social welfare) of six cases.

When these relationships are modeled while accounting for other predictors of issue attention like party, age, incumbency, and gender of the candidate, as well as competitiveness of the race, only social welfare issues remain significantly related to one another across platforms. Again, this suggests that the particular issues candidates choose to talk about may be tailored to the specific platform, rather than part of a broader messaging strategy.

Tone

To examine the question of tone, ads and tweets were separated into three categories: contrast, in which candidates compare themselves to their opponent; promotional, in which candidates paint themselves in a positive light; and attack, in which candidates point out flaws of or misdoings by their opponents (with each type summed by day for each candidate).

There are relatively dramatic differences between television advertisements and campaign tweets: while the advertisements are relatively evenly divided between the three types of ads (42 percent promotional, 35 percent attack, 23 percent contrast), tweets are overwhelmingly positive (81 percent), with only a relatively small number of negative tweets (15 percent) and even fewer contrast tweets (4 percent). This is likely due partially to the 140-character limit imposed by Twitter, which makes clear contrasts between candidates difficult to fit in.

A basic test of whether the tone of tweets tends to imitate that of ads is a simple correlation. Both negative tweets and ads and positive tweets and ads are significantly correlated, while contrast ads and tweets are not. This insignificant finding is likely driven by the extremely low number of contrast tweets.

This pattern of significance remains when we model similarity as a function of other predictors of campaign negativity, like, competitiveness, incumbency, resources, and the same candidate characteristics (gender, age, and party) considered above.

Altogether this suggests that while there is little collusion of message across new and old platforms, once a campaign decides to go negative, it does so across media.

Twitter messaging adapts in real-time

This further suggests that Twitter use is not necessarily constrained by or predetermined by broader campaign message strategy, but can be easily adapted to the real-time flow of information, especially the public and media agendas. Twitter as a real-time, direct communication medium makes it easier to respond to salient issues on a daily basis. Perhaps this implies that the adoption of real-time direct communication technologies will push modern political campaign practices toward greater fluidity.

These changing dynamics among campaigns, the news media, and the public agenda, at the very least, deserve more attention. This also has implications for the type of political information citizens obtain online. While traditional political ads play a role in political education, Twitter seems to include less issue-related information, which may mean that those using Twitter learn different things about campaigns, and receive different types of mobilizing calls to action than those relying on traditional ads.

This blog is based on a recently published article by Leticia Bode, David S. Lassen, Young Mie Kim, Dhavan V. Shah, Erika Franklin Fowler, Travis Ridout, and Michael Franz in the Online Information Review.

Featured image credit: Gage Skidmore (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2iRbFlB

_________________________________

Leticia Bode – Georgetown University

Leticia Bode – Georgetown University

Leticia Bode is an assistant professor in the Communication, Culture, & Technology program at Georgetown University, with affiliate appointment in the Department of Government. Her research focuses on the intersection of politics, technology, and communication.