In A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968, Randal Sheppard explores the major political transformations in Mexico since 1968 through the prism of Mexican revolutionary nationalism to show how nationalist mythology surrounding the revolutionary state has been used to bolster both the elite and growing opposition movements. Sheppard astutely demonstrates the complexities of the post-1968 Mexican context, offering an excellent snapshot of a ‘persistent revolution’, writes Myriam Lamrani.

A Persistent Revolution. History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968. Randal Sheppard. University of New Mexico Press. 2016.

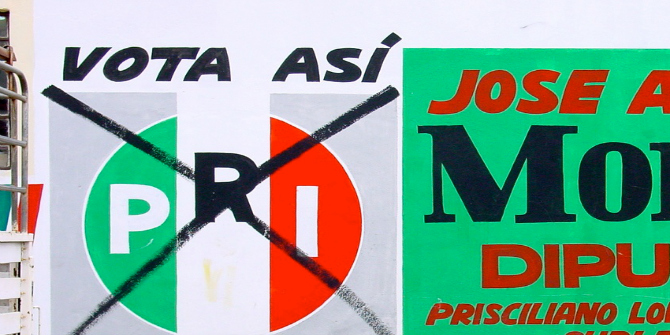

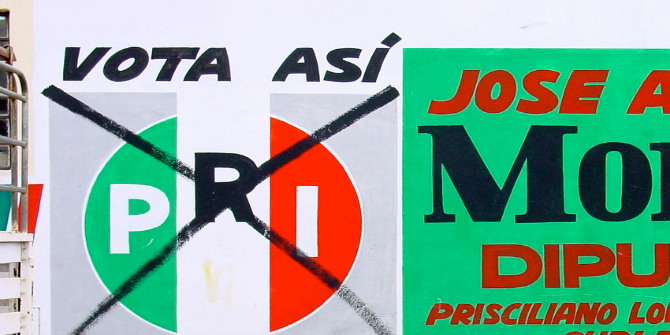

In 1990, Mario Vargas Llosa said: ‘Mexico is the perfect dictatorship.’ The Peruvian Nobel prize-winning writer was explicitly referring to the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), the ruling party that had been in power over the preceding 61 years. In his account of the post-1968 period in Mexico, A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968, Randal Sheppard describes how this political colossus – now back on the political stage since the 2012 elections – ended up having clay feet.

In 1990, Mario Vargas Llosa said: ‘Mexico is the perfect dictatorship.’ The Peruvian Nobel prize-winning writer was explicitly referring to the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), the ruling party that had been in power over the preceding 61 years. In his account of the post-1968 period in Mexico, A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968, Randal Sheppard describes how this political colossus – now back on the political stage since the 2012 elections – ended up having clay feet.

Through a series of historical ‘snapshots’, Sheppard skilfully weaves a narrative of the slow dismantling of the Mexican state and the rise of non-elite political opposition. This shines a light on a gallery of key historical moments and revolutionary symbols prominent in the post-1968 Mexican context. From Emiliano Zapata to Benito Juárez, Sheppard examines the ways in which the political elite represented by the PRI was effectively weakened by a growing opposition movement that made use of the same nationalist revolutionary mythology to undermine the ruling political elite. The ‘Ariadne’s thread’ of this exploration of Mexican identity is precisely the nationalist mythology surrounding the revolutionary state.

The story unfolds through six main sections, each focusing on a specific historical period. Starting the book in Mexico City on 2 October 1968 with the massacre of student protesters by security forces, Sheppard introduces his topic with an event that has been mythologised in Mexico as a symbol of the PRI’s hegemony. Instead, the author argues that the Tlatelolco massacre ‘symbolised a historical rupture’ (23). It was to become a revisionist myth that would serve both the Mexican right and left. Sheppard takes this as his entry point into an exploration of Mexican national identity through the lens of revolutionary nationalism as the country came to experience a neoliberal turn. From there, he goes methodically through the successive presidential administrations, while also describing the appropriation of revolutionary cultural elements by non-elite opposition and grassroots movements.

Image Credit: (Darij and Ana CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Darij and Ana CC BY 2.0)

In Chapter Two, Sheppard explores the de La Madrid administration (1982-88). Symbolising a technocratic turn for the country, this was marked by the increased use of revolutionary imagery to link the government’s neoliberal turn to the ideals of the Revolution, most notably by exploiting the portrait of revolutionary leader Zapata. Chapter Three provides an enthralling description of the rise of civil society consciousness through the emergence of social movements and political opposition in the 1980s by pointing out another important rupture between the nation and the state: the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which killed more than 10,000 people and left hundreds of thousands wounded or homeless.

The PRI government’s inept response was heavily criticised for leaving thousands of citizens organising rescue operations for themselves. Adding to the disgrace, the PRI was held responsible for the collapse of poorly constructed public buildings, thereby hinting at the party’s corruption in the aftermath of the quake, as a strong political opposition led by the PAN (National Action Party) and the Catholic Church emerged. Sheppard argues that this event facilitated an atomisation of the opposition which – and this is the core of his argument – made use of the same democratic rhetoric and symbols of the Revolution that had been endorsed by the PRI. Chapters Four and Five then take us through the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the subsequent rise of the neo-Zapatistas in the jungle of Chiapas.

Culminating with the end of the PRI’s political hegemony in 2000 and the ensuing twelve years of PAN rule, the author concludes an intelligent discussion on the ‘complicated relationship between nationalism, politics, and culture in Mexico’ (18) in creating a Mexican identity that bridges the nation and the state. A Persistent Revolution delivers a fresh outlook on the cultural dynamics woven into post-revolutionary nationalism and historical continuity. It also brings to mind the concept of ‘eternal return’ (sensu Eliade 1949), or the idea that the power of things resides in their origins being enacted in Mexican political rituals around the myth of the Revolution.

If anything is lacking in this book, it is a thorough account of the PRI’s return in 2012 following twelve years of PAN rule. Under the Peña Nieto administration, the PRI state has been at the heart of corruption scandals, including the disappearance of the 43 students from the Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa. This further revealed the collusion between political parties, social movements and non-state actors, such as Mexican criminal syndicates, while seething anger at the Mexican political elite has once again harnessed civil society.

Nonetheless, the key strength of this book is its engagement with the anthropological literature on Mexico and nationalism, thus providing a clear vision on the reappropriation of revolutionary nationalist symbols to ‘contest and shape power relations’ (256), while also preserving historical continuity and the mythology of the Mexican state. Indeed, it is an ambitious task to tackle the concept of identity in Mexico, and this anthropological outlook is much welcome. The result is a portrait that emphasises the eerie resonance between Zapata, the ‘modernisation project’ under the Salinas administration (1988-94), and the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) hailing from the state of Chiapas to wage war against the Mexican government.

In the end, Sheppard goes beyond the usual clichés by including Mexican national heroes such as Benito Juárez and Miguel Hidalgo that are ‘more relevant to Mexicans themselves’ (17). He seeks to dispel the widely held illusion that it was Subcomandante Marcos that defeated the PRI in 2000, whereas in fact it was the Catholic conservative executive, Vicente Fox (2000-06), the man that would inherit the Mexican presidency during one of the bloodiest wars in Mexico’s recent history. In an astute way, Sheppard ends up showing both the Mexican revolutionary mytho-history and our own mythology about Mexico. For anyone eager to grasp the complexities of Mexican political and cultural history through the lens of revolutionary nationalism, this book is an excellent and enjoyable ‘snapshot’ of what is indeed a ‘persistent revolution’.

This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2n5RAKQ

——————————————–

Myriam Lamrani holds a BA in Art History and Archaeology – specialisation in Mesoamerica (ULB, Belgium) – and an MSc in Social Anthropology (UCL). She is currently a PhD candidate in Anthropology at University College London. Her research focuses on the role of the image in politics and popular religion in post-revolutionary Mexico. She is funded by the ERC and is part of the Making Selves, Making Revolutions: Comparatives Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics project (CARP), led by Martin Holbraad (UCL).