Congressional Republicans are now moving rapidly to push through the American Health Care Act, which would repeal and replace President Obama’s signature health care reform, Obamacare. Jonathan Lewallen writes that the GOP’s haste could backfire on them. Writing legislation is a skill, he argues, and in a time of both unified government and budget cuts to Legislative Counsel offices, the chances of the party making a legislative mistake are considerably increased.

Congressional Republicans are now moving rapidly to push through the American Health Care Act, which would repeal and replace President Obama’s signature health care reform, Obamacare. Jonathan Lewallen writes that the GOP’s haste could backfire on them. Writing legislation is a skill, he argues, and in a time of both unified government and budget cuts to Legislative Counsel offices, the chances of the party making a legislative mistake are considerably increased.

“At the end of the day, this should never have happened, and is a product of the rushed way a law was passed”

“The way [the health care proposal] was rolled out was not indicative of an open process.”

The first of those quotes comes from a congressional staffer speaking in 2014 about the King v. Burwell case that arose from the Affordable Care Act. The second is Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C.) this year talking about the new Republican bill to “repeal and replace” Obamacare, the American Health Care Act (AHCA).

Congressional Republican leaders have laid out an ambitious agenda, buoyed by united control of the House, Senate, and White House for the first time in a decade. In addition to changing the landmark health care law, the GOP has already worked to undo late Obama administration regulations on the environment, labor, and energy companies’ payments to foreign governments, and they hope to address banking regulations, the tax code, and access to reproductive health services.

It’s no wonder the then Vice President-Elect Mike Pence told his former colleagues to “buckle up,” in January but my research suggests that Republicans may want to pump the brakes a little, lest their legislation fall victim to drafting errors that could hinder implementation and lead to court cases that would leave their legislative efforts subject to judicial interpretation and put the Supreme Court again at the center of partisan political battles.

Republicans have been stymied by poor legislative drafting before. In 2013, Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.) introduced a government funding proposal that would delay the implementation of the Affordable Care Act by one year—only Graves’s bill would have accidentally funded the entire federal government at $967 million rather than $967 billion, a roughly 99 percent cut in federal spending. And in 2012, the House Republican majority brought up a bill that would establish a moratorium on federal regulatory action until the unemployment rate fell below six percent. There was one problem—the bill originally referred to the “employment” rate rather than unemployment. Republicans brought a corrected version to the floor, only the debate rule that would approve the correction itself had a typo.

As the Democrats’ experience with the Affordable Care Act and the resulting King v. Burwell case showed, a lack of attention to detail is not just a one-party problem. But why is it so hard to write to avoid mistakes like those described above? Because writing legislation is a skill. Whether it’s a large, complex bill to reshape the national health care system or a small measure that would transfer federal land to private hands, the author must translate policy ideas into language understandable enough to be carried out by other people (the bureaucracy, the courts, and the states). It can be done well, or badly; the latter case looks something like trademark law over the last decade, where a change in formatting from a bulleted list to a written paragraph led to inconsistent application across the country.

I examined legislative error more systematically in a recent study, and my results suggest that we could be in for lots of congressional drafting error over the next year and a half. The first challenge is finding evidence of such error, of separating legislative mistakes from instances of delegation to the bureaucracy via vague language. Evidence of one type of congressional error is easy to spot: star prints are corrected editions of congressional bills and committee reports used to fix clerical, technical, or substantive errors, so-called because their title pages feature small black stars. A star-printed bill or report replaces the original in its entirety even if only one word is corrected.

Even then, attribution can still be difficult as it’s not always clear at what stage of the process the error occurred. Nevertheless, measuring congressional drafting error through star prints has the advantage of providing a clear, consistent measure that is traceable across time, across committees, and across issues. Helpfully, the Library of Congress specifies where committee reports have been corrected and so I studied the sources of error on these reports; curiously, they all have come in the Senate.

I found three major factors that increase star prints. The first of these is when the Senate changes majority parties; the Republicans retained their Senate majority, so we don’t have to worry as much about this now. The second is unified party control of the House and Senate, which also increases the number of star prints put out by committees; because Republicans currently have a majority of seats in both chambers, the odds of error occurring should increase by about 10 percent.

Remember what I said about legislative writing being a skill? The third factor that significantly affects congressional drafting error is funding for the Senate Legislative Counsel offices; when funding goes down, errors go up. The Legislative Counsel offices (the House has one too) help members and their staffs translate their policy ideas into bill text.

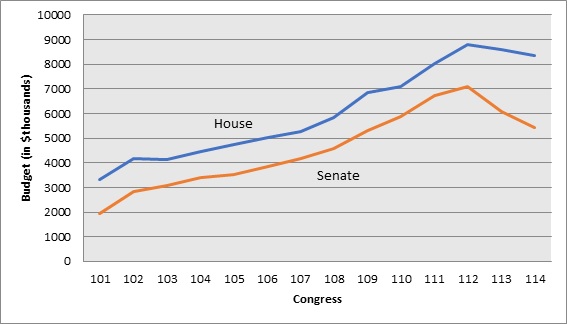

Funding for the two offices steadily increased from the late 1980s (when complete data are available) through Obama’s first term in office. In 2013-2014, though, Congress cut the two Legislative Counsel budgets by 2.6 percent in the House and almost 14 percent in the Senate, and then again in December 2015 by another 2.7 percent in the House and 11.2 percent in the Senate. That was the last time Congress spelled out a budget for the Legislative Counsels, and the continuing resolutions enacted since then have ensured that funding has not changed. In the Senate, the office charged with helping to write bills—its capacity to reduce error—is now operating at its lowest budget since 2006 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 – Funding for Congressional Legislative Counsel Offices, 1988-2016

What does this all mean? The decline in Legislative Counsel funding is yet another example of decreased congressional capacity in recent years. If the AHCA or any other Republican legislation we see this term is not written carefully, Congress could send conflicting information to the other branches of government and find its attempts at changing policy mired in legal battles or subject to bureaucratic interpretation, and the institution’s ability to solve problems may suffer, no matter what kinds of solutions it offers.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Legislative Error and the “Politics of Haste”’, in PS: Political Science & Politics.

Featured image: “Error” by Nick Webb is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2nuX2Hc

_________________________________

Jonathan Lewallen – University of Texas at Austin

Jonathan Lewallen – University of Texas at Austin

Jonathan Lewallen is a PhD Candidate at the University of Texas at Austin specializing in agenda setting and American political institutions. His published research has appeared in PS: Political Science & Politics, Presidential Studies Quarterly, and Regulation & Governance.