Throughout his 2016 presidential election campaign, Donald Trump claimed that the US had been losing its status as the most powerful nation in the world, and that if elected he would “Make America Great Again”. Carla Norrlof writes that while America’s superpower status has changed little in recent decades, Trump was able to feed on the anger of many voters who had not benefited from the US’ promotion of the liberal international order. She argues that the country has little to gain under Trump’s “America First” policies, and those at the bottom would be unlikely to see any significant material gains.

Throughout his 2016 presidential election campaign, Donald Trump claimed that the US had been losing its status as the most powerful nation in the world, and that if elected he would “Make America Great Again”. Carla Norrlof writes that while America’s superpower status has changed little in recent decades, Trump was able to feed on the anger of many voters who had not benefited from the US’ promotion of the liberal international order. She argues that the country has little to gain under Trump’s “America First” policies, and those at the bottom would be unlikely to see any significant material gains.

What role has inequality played in shifting US domestic support for the post-war liberal international order (LIO)? Inequality undoubtedly played a role in bringing Trump to power. Part of the electorate voted for him because of the way he framed America’s challenge. In 2016, his warnings of lost greatness, and his pledge to ensure a fairer distribution of the gains from international cooperation in order to “Make America Great Again” (MAGA)—was a siren call. The widening gap between rich and poor Americans contributed to making the MAGA slogan a rallying cry for his campaign. But while economic woes may explain some of his support—income and income growth do not fully capture Trump’s anti-globalization appeal. Education and race were much stronger predictors of the 2016 vote.

What’s at stake?

Until the election of Donald J. Trump, every president since the end of World War II has supported the LIO, a US-led international framework promoting stable and peaceful interstate relations, open economic relations and individual freedoms, in a rules-based system backed-up by American military power.

Trump is not the first to be worried about the United States’ standing in the world. A lively debate erupted in the 1970s and 1980s involving both English and American scholars based on the shared understanding that the US was declining relative to other countries, especially the Soviet Union, Japan and West Germany. Pessimism regarding the United States’ slippage in the ranks of the great powers persisted, as worries about external challengers, economic decline, and over-extension predated Trump’s rise to power. Those who advocated a policy of foreign policy restraint were primarily concerned with US military projection and only marginally preoccupied with America’s economic engagement. Though some were troubled by the economic implications of US military spending, mainstream scholars never really questioned America’s willingness to lead the economic dimension of the LIO. Even politicians such as Senator Robert Taft operating in the 1940s and 1950s, George McGovern in the 1970s and Pat Buchanan in the 1990s were primarily concerned about US military spending, its involvement in foreign wars and the drain of allied relations.

Trump’s criticisms of the LIO are not limited to America’s role in security affairs but extend to America’s economic relationships, particularly commerce. The 2016 election campaign, the inaugural speech, numerous official speeches, and the emerging Trump doctrine as laid out in the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS), all propose a radical break with the LIO in order to prevent other countries from taking advantage of the US.

Is America’s ‘lost greatness’ for real?

While America underwent relative decline in comparison to some countries, on some dimensions, America’s superpower status remained remarkably resilient throughout the 1990s and even in the 2000s due to the reinforcing logics between the US’ advantages as the largest economy, issuer of the global currency, and possessing the strongest military. In fact, on all relevant power metrics, the US has sustained its preeminent position in the international system.

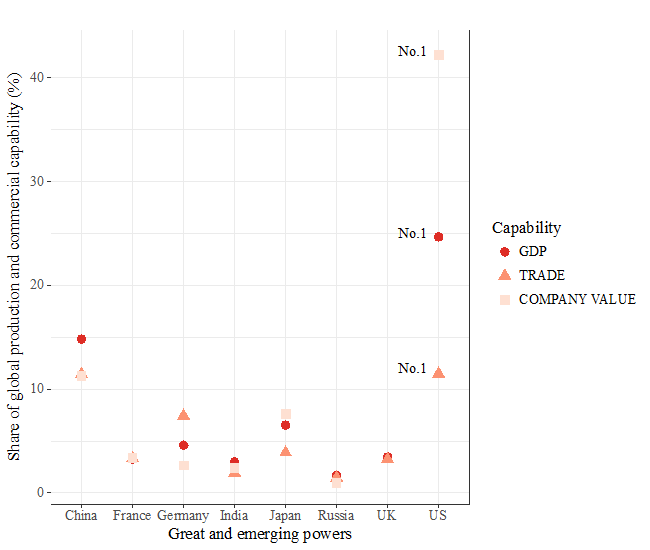

Figure 1 shows the global share of GDP and commercial capability of the great powers and emerging powers in the international system. The US occupies the number one position on all measures. As is plainly visible, the US narrowly surpasses China in the trade realm. But there are several reasons why exports and imports aren’t the best way to gauge commercial power.

Figure 1 – Great Power production and commercial capability, 2016

Source: International Affairs

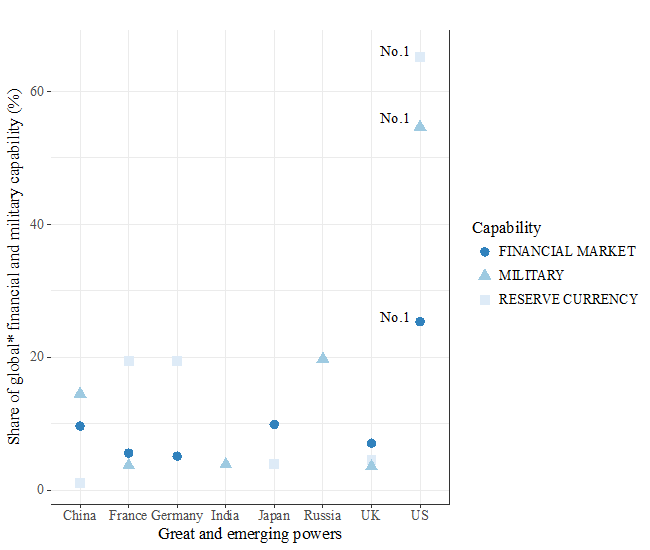

Figure 2 shows the great power and emerging power share of global financial and military capability. The US is clearly in a league of its own. The only metric where other great powers come close is in regards to financial market size, and even so the main contenders, Japan and China are at least 15 percentage points short. Figure 2 also underplays America’s lead in the reserve currency domain. The nearest competitors, France and Germany jointly (along with 17 other countries) provide the euro and have no independent reserve clout. The US has no military rival.

“Traces of Trump” by Quinn Dombrowski is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

In reality, the US has performed very well under the liberal international order (LIO), and attempts to further skew gains from international cooperation are unlikely to be successful. Even if the US managed to alter the international distribution of income and wealth, it remains unclear whether Americans who have seen their income stagnate would benefit.

Figure 2 – Great Power financial and military capability, 2016

Source: International Affairs Note: *Financial and reserve currency capability relative to global capability; military capability relative to great power capability.

The gap between America’s rich and the poor has been growing …

President Trump has correctly identified a distribution problem. But he mischaracterizes its nature. The real threat to American prosperity is not unequal external redistribution but unequal internal redistribution. The liberal dilemma is not that the LIO distributes gains unfavourably to the United States, but that not everyone in the United States ‘wins’ because US domestic policies have been out of step with global economic integration. If US domestic policies had redistributed income and opportunities by providing labour and trade adjustment programs, a wider social safety net including more spending on health and education, the benefits from international cooperation would have been more widely shared.

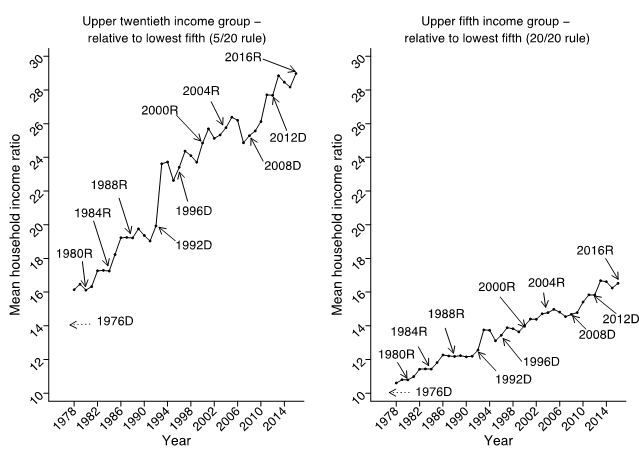

As shown in Figure 3, income inequality in the US has been rising since the late 1970s. And the gap between the rich and the poor has increased irrespective of whether the president in power has been a Republican or a Democrat. Given the trend of greater income dispersion in the US—how were income concerns (assuming they played a role) mobilized to effect in the 2016 presidential election?

Figure 3 – Income inequality between the top and bottom income earners in the United States, 1978–2016

Source: International Affairs

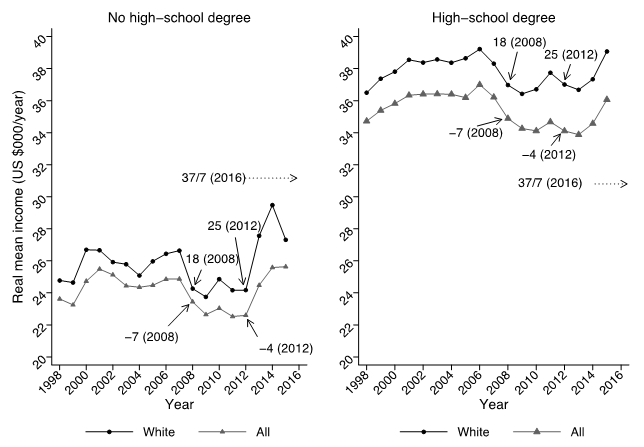

Income concerns mattered for the vote but primarily in the way that it intersected with other factors, specifically education and race. As show in the right and left panel of Figure 4, the vote margin (the difference in percentage of votes between Republicans and Democrats) in the 2016 election was very high (37 point margin) for white voters without a college degree, considerably higher than for all voters taken together (7 point margin). White voters without college degrees were more likely to vote for Trump despite absolute higher income levels, and higher income growth during Obama’s two terms, than all voters taken together without college degrees. White voters without college degrees were also more likely to vote for Trump than white voters with college degrees (3 point margin) despite experiencing more favourable income growth during Obama’s presidency than white voters in higher education brackets.

Even in distressed regions, the Rust Belt (Pennsylvania in the north-east; Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan and Ohio in the mid-west), where the Democrats saw their ‘blue wall’ fall—race was a stronger predictor of the 2016 vote than income. As one might expect, racial polarization was also high in the south.

In addition to the 2016 vote being racially patterned, racist attitudes encouraged a portion of the white electorate to align with Trump.

Figure 4 – Income growth among US citizens with education below college degree level, 1998–2016

Source: International Affairs

Trump’s call to put America ‘first’ internationally, and white Christians ‘first’ domestically, resonated with non-college-educated white voters who had seen their historic privileges slip away. The relationship between education and race was first noted in Myrdal’s 1944 book, An American dilemma, commissioned by the Carnegie foundation. The Swedish Nobel laureate exposed the tension between liberal ideals and the reality of racial discrimination in the US, and called for an ‘educational offensive against racial intolerance’. His findings ring true today.

Shoring up support for the liberal international order will require strengthening the liberal foundations of American society. Increasing access to higher education remains an effective way to fight racism, up to a point. Beware the liberal playbook…

- This article is based on ‘Hegemony and inequality: Trump and the liberal playbook’, in International Affairs, available ungated until the end of February 2018.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ogsk4l

_________________________________

About the author

Carla Norrlof – University of Toronto

Carla Norrlof – University of Toronto

Carla Norrlof is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto. Her research is on theories of international cooperation with a special focus on great powers particularly US hegemony in the areas of money, trade and security.