As the ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda drops all charges against Kenya’s leader, LSE’s Fiona Mungai and Yusuf Kiranda argue that it is time for African countries to strengthen their judicial institutions.

The recent collapse of the International Criminal Court (ICC) case against Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta does not come as a surprise. The turn of events was perhaps expected owing to the incessant failure of the Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, to gather crucial evidence against the President. Uhuru Kenyatta faced charges of crimes against humanity after a wave of violence erupted following the 2008 elections. Besides this development setting precedence as the first trial to challenge the pertinence of the international courts in delivering justice to Africa, it raises fundamental questions regarding the future of the ICC.

The ICC has been a recipient of endless criticism over the last four years while conducting the Kenyan cases. A continuum of granular issues has emerged, varying from political manipulation of the court, lack of independence from its largely European backed financiers to revelations of gross incompetence on the part of the Prosecutor. Moreover, legitimate concerns have been raised regarding the refusal of the USA, Israel and China to participate as signatories to the Rome Statute. In the eyes of many, the trio could in several instances be culpable for crimes against humanity. The fact that the court has only indicted Africans and ignored other perpetrators of greater atrocities cannot be ignored or underestimated as a major weakness.

While recognising the above concerns, it is only prudent to acknowledge that in 2002, African states willfully participated as co-authors and signatories to the Rome Statute that govern the ICC. This was greatly influenced by the fact that African countries had inherited weak institutions from the colonialists and the period post-independence witnessed phases of democratic rollbacks that did not support the development of sophisticated domestic judicial systems. Therefore, they looked to the ICC to deliver impartial, competent and independent justice. In doing so, it can be argued empirically that Africans passed the no confidence vote upon their own institutions.

Could it be that Africa simply accepted the ICC in the same way the continent has been on the receiving end of western-developed solutions to western-identified problems? This is a phenomenon that we can trace from more than 100 years back. When European explorers discovered “backwardness” and disease in Africa, colonialism was the prescription. Later on, following independence, another problem – underdevelopment and poverty was identified and the solution was aid. When it came to impunity and war crimes, the ICC was invented. In all these instances there have been no homegrown solutions or lessons drawn upon Africa’s ability to deal with complex challenges. Could the collapse of President Kenyatta’s case present a unique opportunity for Africa to candidly and dispassionately introspect in the same way it opted out of colonisation?

It is our considered view, that the ICC has failed Africa and these concerns cannot be put to sleep. We express no opinion on Uhuru’s guilt or innocence, but rather our strong concern is focused on ICC’s incompetence, structural or otherwise, which has led to the collapse of a crucial case. The victims of Kenya’s post-election violence will forever live with a feeling of abandonment by an institution in which they placed so much hope. It is evident that like earlier western neo-colonial systems, the ICC too is highly unlikely to deliver.

Our hope in resolving crisis in Africa may lay in reconciliation- an indigenous peace model that was conceived and aptly implemented by the great pan-African leaders such as Jomo Kenyatta and Kamuzu Banda. LSE’s distinguished Professor Thandika Mkandawire, Chair in Africa Development paradoxically pointed out that Nelson Mandela was awarded a much deserved Nobel Peace Prize for his reconciliatory efforts in South Africa, however when Africans opt for reconciliation as a tool for justice, the West brands it as impunity.

It is therefore critical that Africa realises that the panacea to justice will rely on strengthening our own judicial institutions. Reconciliation will only serve to augment these institutions. A regional court would be a worthwhile venture to pursue. There is no substitute to solving our problems domestically. It is not just a bold step – it is a necessity.

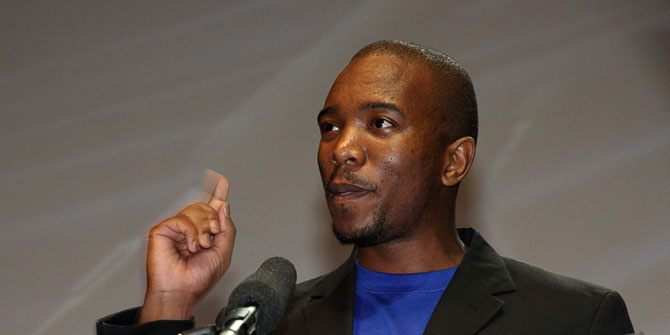

Fiona Mungai and Yusuf Kiranda are LSE graduate students and Program for African Leadership (PfAL) Fellows.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

You should have a look at how the ICC and more generally international criminal tribunals work. There is no opposition between domestic courts and the ICC.

First, the ICC statute allows the Prosecutors to stop its investigation and engage in a process of transitional justice if needed. Same for the jurisdiction of the ICC, according to the complementary principle, the ICC is only in charge of cases when local courts have been proven unable or unwiling to sue or to investigate.

These two examples show that far from being a neocolonial institution the ICC actually try to balance its approach between the need for justice and the need to empower local governments/ institutions.

This is the positive consequence of the involvement of African countries during the negotiations stage. The ICC still has some flaws but before labeling it as neocolonial, have a look at the legal provisions !