Ahead of her performance at the Africa Writes Destival in London, LSE’s Melissa Kiguwa discusses her sources of inspiration.

Melissa Kiguwa is building a reputation as one of the best emerging writing talents from the African continent. She was longlisted for the 2014 Writivism Short Story Prize for her story, The Wound of Shrinking. Her first collection of poems, Reveries of Longing, published in June 2014, was recently selected as one of This is Africa’s 100 best books in fiction, poetry, memoir and non-fiction, published between 2010 and 2014. She has also been recognised as an influential African feminist artist to know and celebrate.

Kiguwa has spent the last year at LSE, studying for a MSc in Media, Communications and Development , but she will be taking some time out to perform poetry at the upcoming Africa Writes Festival on 4 July 2015.

What themes dominate your work?

When I first started writing, like most people, it was as an outlet rather than as a craft. My first collection is indicative of that—there are a lot of young angry poems that spoke to all the different places I was travelling metaphysically and intellectually. Reveries of Longing is about migration, exile, the irrationality of constructed geopolitical borders and the inequity embedded in the modern-day state. It is a mixture of spoken word pieces and on the page poems. It is a collection that is struggling: struggling between honouring the sacred and being blasphemous, honouring afro-indigenous cultural knowledges in the face of neoliberal imperialism while being a product of neoliberal imperialism, etc. And while there is a lot of cognitive dissonance, I feel like all of this is appropriate for the collection. In both theme and structure, the poems are about defiance, taboo, and placing oneself in the confusion of it all. Those poems were extremely inspired by the poets whose work I deeply resonated with at the time: Sonia Sanchez, Amiri Baraka, Lucille Clifton, Ntozake Shange, Gil Scott-Heron, etc.

Today, I would say I am much more interested in nuance, in the slow tide of emotions breaking open and closing again. My writing is still interested in those young angry poems and it is still unabashedly dedicated to celebrating Blackness in all of its global manifestations, but it is also interested in solitude, melancholia, and unrelenting passion. The poems I write now are longer, they are their own sort of prose-poems. There are many questions about the place of ritual, somatic healing, intergenerational trauma, the work of de-colonial love, and the selves that we are outside of narratives of efficiency and productivity.

I am constantly asking myself (and therefore my poems are also constantly asking): Who am I in the singular and perhaps even multiple modalities of my subjective self and how is that related to the larger psycho-social economic contexts around me?

I am extremely interested in rituals as both a form of resistance to neo-colonialism but also in rebuilding communities and sense(s) of self. What rituals do individuals and communities perform after land-grabs happen? What are the rituals of the mothers of those Black men shot down in the street by police officers in the United States? What are the rituals of lovers separated by immigration detention centres? What are the rituals of pregnant incarcerated women? How are we loving ourselves, how are we talking to ourselves, and how are we healing ourselves?

Does history (or herstory) have something to teach us? Which books do we read and where do we find them? What are our points of reference and whose voices and knowledges are legitimate?

What has led you to feel so passionate about these themes?

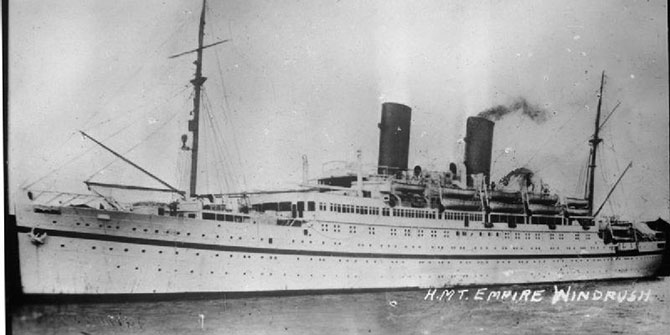

I think the themes I explore are extremely close to home. I have either lived or loved people whose stories I write about. Personally, I was raised by a migrant mother whose fierce determination to have a better life saw us migrate transnationally. I’m still in awe of the ways she, in her youth, managed to navigate various immigration centres, rules, and financial burdens to get her and I to new worlds. I attended more than 10 schools growing up. I have lived, loved, and nurtured a broken heart on three different continents. I have sat and drunk tea with women in refugee camps, I have danced in secret pubs for lesbian women and gay men, and cried at the indecency of dehumanisation at border patrol checkpoints.

I am always cognisant that for the majority of the world, the pendulum swings between destitution and vulnerability. I always try and remind friends lamenting “the state of the world” that their (our) reality of mobility, privilege and access to relative luxuries is limited to such a small percentage of the larger global population. Most people will never leave their home (unless by force), most people will continue to know and see their locality as the only plane of reality, and most people will continue to live and survive just like human beings have been doing since we inhabited this planet. But I also understand that vulnerability is ever present. In 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, we all saw how even the world’s superpower was susceptible to the kinds of realities people around the world face regularly. I think that was a powerful and painful moment in the global narrative of the contemporary state because it told people around the world that regardless of where you live, if you are poor and your ethnicity is the “unchosen” in your land, your life is deemed unworthy.

There is a line in the film adaptation of Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, where the main protagonist says, “I’m poor, I’m black, I might even be ugly, but dear God, I’m here.” I feel this embodies the root of my work. That regardless of where in the margins of the communities (we) are located, we are here. And we require voice and the dignity to tell our own stories. We are allowed to be enraged, to be tender, to be graceful, and to be clumsy. We are allowed to self-determine and we are most certainly allowed to seek freedom in all the messy ways freedom is sought after.

You have spent the 2014/2015 academic year in London studying at LSE, has the city and/or your course provided any new inspiration for your writing?

Right after receiving my first degree in political science at the University of Arizona I immediately moved to New York City. I was 20 and felt that the big city was exactly what I needed. I was there for about six or seven months and realised I had made a big mistake and I moved to Kampala, Uganda. Being in London has reminded me of that urban hustle. Of the grit and tenacity embedded in immigrant weariness. But there is also a lot of flavour, as is the case in most major metropolises. Of course some of this shows up in my writing, but mostly I am interested in the emotionality of it all. Who are we outside of, inside of, and while navigating between these constructs.

If so, are we likely to hear you perform any of this new work at the Africa Writes Festival?

I will most definitely be performing my new work at Africa Writes Festival. The first stanza of the poem I am performing reads:

“because this is a sorrow I had not carried before, ask my mother to tourniquet the tulips falling from the bayou of my lashes, the sponge from my marrow. for we were once spring hiding beneath winding vines of evening primrose, the mischief of our nights a call to wild of sombre childhoods. some would call our hiding suffocation, an asphyxiation bellied under throes of looming foliage, but we knew better, didn’t we? that inside shrubs of decay lies the other side of your tongue, its slickness a bastion of insatiable hunger resting outside, aware from, in front of, gathering over and over again…”

Melissa will be performing at the Africa Writes Festival on Saturday 4 July from 15.45 to 16.30 in Contemporary African Lyrics: Poetry in Performance. Entrance is free.

Melissa Kiguwa is a postgraduate student in the Department of Media and Communications at LSE. Follow her on Twitter @mkiguwa. She is the author of a collection of poems, Reveries of Longing.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

5 Comments